Barrett's oesophagus

Your health expert: Dr Rehan Haidry, Consultant Gastroenterologist

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, August 2023

Next review due August 2026

Barrett's oesophagus is when the lower section of your food pipe (oesophagus) is damaged by acid and bile coming back up from your stomach. Over time, the cells of the lining can be replaced by a different type of cell, similar to those that grow in your bowel. This can increase your risk of developing oesophageal cancer. But most people with Barrett’s oesophagus don’t get cancer.

About Barrett's oesophagus

Barrett’s oesophagus is named after the surgeon who first described it. It affects up to two in every 100 people, and is more common in men. You can get it at any age, but most people diagnosed are over 50.

Causes of Barrett's oesophagus

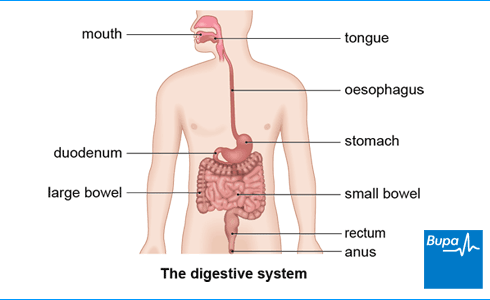

Barrett's oesophagus is caused by long-term reflux of acid or bile into your oesophagus (food pipe). Your oesophagus is the tube that joins your mouth to your stomach. When acid and bile come back up your oesophagus from your stomach, this is known as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) or acid reflux.

Usually, stomach contents are kept in your stomach by a muscular valve. If you have Barrett's oesophagus, this valve may have become weak or moved out of place. Acid and bile from your stomach can then leak upwards.

Over time, the acid and bile from your stomach can cause the cells in the lower part of your oesophagus to become inflamed and damaged. They eventually get replaced by new cells, which are more like the cells that line your stomach. This is your body’s way of protecting the lining of your oesophagus from further damage.

You're more likely to get Barrett’s oesophagus if you have long-term reflux and you:

- are male

- are white

- are over 50

- have someone else in your close family with the condition

- have a hiatus hernia

- smoke

- are overweight, particularly around your waist

Only about one in every 10 people with chronic reflux go on to develop Barrett's oesophagus. You're more likely to develop it if you’ve had severe reflux symptoms for many years.

Symptoms of Barrett's oesophagus

You may not have any symptoms of Barrett’s oesophagus. But you may have symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), which causes Barrett’s oesophagus. Symptoms of GORD include:

- heartburn

- acid coming up into the back of your mouth

- food coming back up (regurgitation)

Other symptoms can include a sore throat and hoarse voice, caused by the acid reflux. Acid reflux may also cause coughing or wheezing, and chest pain.

Your pharmacist can suggest treatments to help with heartburn or indigestion. But if your symptoms continue, see your GP for advice., If you have Barrett’s oesophagus, your doctor can give you treatment and check-ups to help prevent cancer or pick it up at an early stage.

Diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and may examine you. They may also ask about your medical history.

Your GP may test for Barret’s oesophagus using a cytosponge. This is a small sponge contained in a dissolvable capsule that’s attached to a fine string. You swallow the capsule and the coating dissolves in your stomach to release the sponge. After about five to seven minutes, your GP will pull the sponge back up (using the thread). Along the way, the sponge collects cells from the lining of your oesophagus. These are then examined in a lab to see if they’re normal or not.

If the cells collected by a cytosponge are abnormal, your GP may arrange for you to have a test at the hospital called a gastroscopy (endoscopy). Or you may have this test straight away without having a cytosponge test first.

In a gastroscopy, a doctor or nurse will put a narrow, flexible tube into your mouth or nose and down into your stomach. This tube has a camera on the end so your doctor or nurse can see inside your oesophagus and stomach. Your doctor or nurse will usually take small samples of tissue (biopsies) from the lining of your oesophagus. They’ll send these to a laboratory to check for any abnormal cells.

Barrett's oesophagus is sometimes picked up if you have a gastroscopy to investigate another problem, such as tummy (abdominal) pain.

Your doctor may ask you to have regular gastroscopies to check for very early signs of cancer, usually every six months to five years. The timing will depend on how abnormal your cells are and how much of your oesophagus is affected. This is because sometimes, changed cells in your oesophagus can become pre-cancerous and eventually cancerous. Doctors call precancerous cells dysplasia (diss-play-zee-ah). Cells that are only slightly abnormal are known as low-grade dysplasia; cells that are more abnormal are known as high-grade dysplasia. The level of dysplasia of your cells determines if you need treatment and what treatment you have. You don’t always need to have Barrett's oesophagus monitored in this way.

Your doctor will talk to you about the benefits and risks of regular monitoring, and what might be best for you.

Self-help for Barrett's oesophagus

Your doctor may ask you to make some changes to your lifestyle to help reduce acid reflux. This won’t get rid of the Barrett’s oesophagus, but it may help to control indigestion symptoms and help to stop your condition getting worse. For example, they might suggest you:

- lose weight if you’re overweight

- stop smoking

- eat smaller meals at regular intervals, rather than a large portion in one go

- use an extra pillow or two or raise the head of your bed if you get symptoms at night

- sit upright when you eat and don’t lie down immediately after eating

- don’t have any hot drinks, alcohol, or food within three hours of going to bed

Barrett’s oesophagus diet

It may help to keep a food and symptom diary (PDF, 1.4MB), to find out which foods make your symptoms worse. Everyone’s different, but some people find that fatty, spicy, or acidic foods, and alcohol and caffeine can cause indigestion and reflux. Depending on the findings from your diary, you may find it helpful to:

- avoid food and drinks that make your symptoms worse

- grill foods instead of frying

- eat less or no fatty and processed meats and cheese

- cut down on coffee, chocolate and soft drinks that contain caffeine, including energy drinks

- cut down or avoid alcohol and fizzy drinks

- not eat acidic foods such as tomatoes, citrus fruits, and juices

- not eat spicy foods

- not have acidic sauces and condiments such as ketchup, mustard, and vinegar

Treatment of Barrett's oesophagus

Barrett's oesophagus treatment aims to prevent further gastro-oesophageal reflux. And, if necessary, remove damaged areas of tissue from your oesophagus.

Medicines

Your doctor may prescribe medicines to reduce the amount of stomach acid you produce. This should help to reduce gastro-oesophageal reflux. You may have medicines called proton pump inhibitors, and need to take these medicines long-term to control your symptoms. If you want to stop taking these medicines, talk to your doctor first, because you may need to do this gradually and take a lower dose to start with.

If medicines don't work, your GP may ask the specialist to see you again to discuss further treatment.

Non-surgical treatment

If tests show that you have pre-cancerous cells, you may need to be monitored with further gastroscopies or treatment. A team of doctors will look at your results and recommend the best treatment options for you. Your wishes will also be taken into account.

They may suggest treatment to remove the layer of damaged cells using a gastroscope. This is called endoscopic treatment. It allows healthy cells to regrow over the area.

Endoscopic treatments include the following.

- Radiofrequency ablation uses heat made by radio waves to destroy abnormal cells. This is the most common way to treat Barrett’s oesophagus in the UK. Your doctor uses a probe to destroy abnormal cells in your oesophagus.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection is a treatment to remove growths of affected tissue from the wall of your oesophagus. This is often used to remove very early cancer of the oesophagus. You may have radiofrequency ablation afterwards. This is to help get rid of any remaining damaged cells.

- Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a treatment to remove precancerous and cancerous areas under the lining of your oesophagus. It aims to remove any potential cancerous lesion intact and with an area of healthy tissue around it.

Your doctor or surgeon will tell you if any of these treatments are suitable for you. They might not be available in all hospitals, so you may need to go to a hospital that specialises in them

Surgery

There are two main types of surgery for Barrett's oesophagus.

Fundoplication

This operation strengthens the valve at the bottom of your oesophagus. The aim is to prevent further gastro-oesophageal reflux. Fundoplication surgery may help if proton pump inhibitor medicines don’t work for you. Your specialist will tell you if this is an option for you.

Oesophagectomy

Your doctor may suggest this operation if you’ve developed an early cancer. Your surgeon will remove the affected section of your oesophagus. They’ll then join your stomach to the remaining part.

Need a GP appointment? Telephone or Video GP service

With our GP services, we aim to give you an appointment the same day, subject to availability.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0343 253 8381∧

Complications of Barrett's oesophagus

The most important complication of Barrett’s oesophagus is that it can sometimes lead to a type of oesophageal cancer. But the risk of developing precancerous cells is low. Most people with Barrett’s oesophagus don’t get cancer.

People who develop cancer have usually had Barrett’s oesophagus for many years. The cancer risk is much lower if you’ve had endoscopic treatment.

If you have Barrett’s oesophagus, you may get other complications linked to gastro-oesophageal reflux. These include:

- inflammation of your oesophagus (oesophagitis) – your oesophagus is damaged by stomach acid and this can lead to ulcers

- scarring of your oesophagus (stricture) – this can narrow your oesophagus and make it more difficult to swallow

You may not have any symptoms of Barrett’s oesophagus. But you may get symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), which causes Barrett’s oesophagus. These symptoms include heartburn, acid coming up into the back of your mouth, and food coming back up. You may also get a sore throat and hoarse voice.

For more information, see our section on symptoms of Barrett’s oesophagus.

It depends on your individual circumstances but there are treatments that can cure Barrett's oesophagus. Examples include destroying or removing the affected cells with treatments called radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). But there’s a small risk that the Barrett’s could come back. So your doctor will want to continue to monitor you.

For more information, see our section on treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Yes, radiofrequency ablation therapy can often cure Barrett's oesophagus. Radiofrequency ablation uses a probe and heat made by radio waves to destroy abnormal cells in your oesophagus. After treatment, you’ll have regular tests to check that your oesophagus is still healthy because Barrett's oesophagus can come back.

For more information, see our section on treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Most people with Barrett's oesophagus don't go on to develop cancer, but if you do, it usually takes many years. If you have Barrett’s oesophagus, it’s important to follow any advice your doctor gives you and to attend regular check-ups. This will help your doctor to spot any abnormal changes as early as possible if a cancer does start to develop.

For more information, see our section on complications of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Barrett’s oesophagus isn’t serious in itself but it can sometimes develop into oesophageal cancer, which is serious. Most people with Barrett’s oesophagus don’t go on to develop cancer. But it’s important to attend regular check-ups so your doctor can detect and treat any potential problems as early as possible.

For more information, see our section on complications of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Hiatus hernia

Fundoplication

Fundoplication is an operation to treat gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) when it can’t be controlled with lifestyle changes and medicines.

Gastroscopy

A gastroscopy is a procedure that allows a doctor to look inside your oesophagus , your stomach and part of your small intestine.

Indigestion

Indigestion medicines can be used to relieve pain or discomfort in your upper abdomen (tummy) or chest that may occur soon after meals.

Indigestion medicines

This information is for you if you have indigestion and are considering seeing your doctor.

Did our Barrett's oesophagus information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Barrett's oesophagus. Patient. patient.info, last updated 17 March 2023

- Barrett's oesophagus. Guts UK! gutscharity.org.uk, accessed 29 June 2023

- Barrett's oesophagus and stage 1 oesophageal adenocarcinoma: Monitoring and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 8 February 2023

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus: an updated ACG guideline. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117(4):559–87. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

- Barrett esophagus. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 3 April 2023

- Dyspepsia – proven GORD. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised December 2022

- Barrett's oesophagus. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 27 November 2019

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Patient. patient.info, last updated 19 March 2020

- Barrett's oesophagus. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 29 May 2023

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: Investigation and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, last updated 18 October 2019

- Cytosponge for detecting abnormal cells in the oesophagus. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 15 December 2020

- Mukhtar M, Alzubaidee MJ, Dwarampudi RS, et al. Role of non-pharmacological interventions and weight loss in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese individuals: a systematic review. Cureus 2022; 14(8):e28637. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28637

- Nutrition in gastrointestinal diseases. Oxford Handbook of Nutrition and Dietetics. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published April 2020

- Zhang M, Hou ZK, Huang ZB, et al. Dietary and lifestyle factors related to gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2021; 17:305–23. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S296680

- Treatment for Barrett's oesophagus. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 27 November 2019

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Di Pietro M, Fitzgerald RC. Revised British Society of Gastroenterology recommendation on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus with low-grade dysplasia. Gut 2018;67:392-393. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314135

- Endoscopic submucosal dissection of oesophageal dysplasia and neoplasia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 22 September 2010

- Nieuwenhuis EA, Pech O, Bergman JJGHM, et al. Role of endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in the management of Barrett’s related neoplasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 2021; 31(1):171–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2020.09.001

- Surgery to remove your oesophagus. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 6 December 2019

- Gastrointestinal medicine. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published June 2020

- Barrett's oesophagus. Macmillan. www.macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 30 September 2019

- Oesophageal cancer. Prognosis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 5 June 2023