Cystitis

Your health expert: Dr Samantha Wild, Clinical Lead for Women's Health and Bupa GP

Content editor review by Pippa Coulter, April 2023

Next review due April 2026

Cystitis is a common type of urinary tract infection (UTI) affecting your bladder. It’s usually caused by a bacterial infection. For most people, cystitis clears up on its own in a few days. But sometimes you may need treatment to help get rid of it and prevent complications.

About cystitis

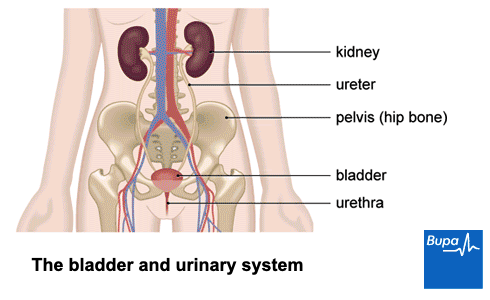

You usually get cystitis when bacteria enter your bladder through your urethra. Your urethra is the tube that carries urine out of your body. This can happen if bacteria from your back passage (rectum) or vagina spread to the opening of your urethra.

It’s also possible for bacteria to enter your bladder directly (for example, during surgery on your bladder or if you have a catheter). The bacteria may also come from your bloodstream.

You’re more likely to get cystitis if you have a vagina than if you have a penis. This is because if you have a vagina, your urethra is closer to your back passage. Also, your urethra will be shorter. This means bacteria don’t have as far to travel to reach the bladder. Around half of women will get a urinary tract infection such as cystitis at some point in their lifetime. Older men are more likely to get cystitis than younger men.

Types of cystitis

You may hear different terms used to describe cystitis. Your doctor may just call it a UTI (urinary tract infection) rather than cystitis.

- An uncomplicated UTI is when you don’t have any other underlying health problems increasing your risk. The infection usually clears up easily by itself or with antibiotic treatment and doesn’t cause too many problems.

- A complicated UTI means you may have other health conditions that can make the infection more dangerous for you. It may be harder to get rid of it, or you may be at greater risk of complications. For more information, see our section on complications.

- A recurrent UTI is when your infection keeps coming back. It usually means you’ve had two or more episodes within six months, or three or more within one year.

Sometimes you can have symptoms of cystitis without any signs of a bacterial infection. This is called interstitial cystitis, or painful bladder syndrome. Interstitial cystitis is a different condition. It may be caused by a problem with your bladder or immune system, or changes to your nervous system.

Causes of cystitis

Cystitis is caused by a bacterial infection. Around eight in every 10 cases of cystitis are caused by bacteria called Escherichia coli (E. coli). These bacteria usually live harmlessly in your bowel or vagina.

Certain things can increase your risk of developing cystitis. These include the following.

- Having sex. Bacteria from your vagina or back passage may get into your urethra when you have sex.

- Having a new sexual partner in the last year.

- Conditions that affect the structure of your urinary tract or how it works. This may make it easier for bacteria to enter your bladder.

- Not being able to completely empty your bladder. In men, this is often due to an enlarged prostate.

- Pregnancy. Pregnancy hormones and your growing uterus make it harder to empty your bladder when you’re pregnant. This can make UTIs more likely.

- Having a weakened immune system. Anything that weakens your immune system – including diabetes and HIV – can increase your risk of infection.

- Menopause. Low oestrogen levels can make your urethra wall thinner. This can make you more prone to cystitis.

- Having a catheter (a tube that’s put into your urethra to drain urine out of your bladder). Your risk of cystitis increases the longer you have the catheter. Other procedures or surgery on your urinary tract also increase risk.

- Some types of contraception. Using a diaphragm or spermicide-coated condoms may make you more likely to get cystitis.

- Stones (calculi) in your urinary system – kidney stones or bladder stones. These can trap bacteria, causing an infection.

- Your mother having a history of UTIs.

If you’ve already had cystitis, your risk of getting it again is higher. This is even more likely if you had it as a child.

Symptoms of cystitis

Typical symptoms of cystitis include:

- burning or stinging when you pee

- needing to pee regularly, but only passing a little urine

- needing to pee more often at night

- a strong urge to pee, which can cause incontinence (peeing without meaning to)

- cloudy, dark or strong-smelling urine

- blood in your urine – you may not be able to see the blood, but it can be picked up in urine tests

- pain in your lower tummy

You may also get more general symptoms, including:

- tiredness or feeling generally unwell

- a high temperature (fever)

- feeling or being sick

- feeling confused (especially older people)

Some people may have the general symptoms without the typical symptoms of a UTI. It’s also possible to not get any symptoms at all with cystitis. You may only find out you have it if you have a routine urine test for another reason.

Children with cystitis may have symptoms similar to adults, including pain when they pee, peeing more often or wetting the bed. Their urine may also have a bad smell. Younger children and babies may be more likely to have a high temperature, sickness, be irritable and not want to eat or feed.

Cystitis symptoms can come on very suddenly. They may be so bad that you find it hard to do your usual activities.

Seeking help for cystitis symptoms

Cystitis normally clears up on its own. But if your symptoms aren’t starting to get better after a few days, you should see a GP.

Some pharmacies in the UK can test you for cystitis and prescribe antibiotics if you have a bacterial infection. You may be able to talk to your pharmacist rather than seeing a GP if they offer this service.

It’s important that you see a GP straight away if you:

- can see blood in your urine

- are male and you have any UTI symptoms

- think your baby or child may have cystitis

- are pregnant and think you may have cystitis

- keep getting infections, despite trying self-help measures

- have other long-term illnesses that affect your immune system, like diabetes

- are feeling very unwell with a temperature or shivers, pain in your sides, or vomiting

Diagnosis of cystitis

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. They may also ask about your medical history. Your GP will often be able to diagnose cystitis from your symptoms without doing any tests. But they may ask for a sample of your urine to check for signs of a bacterial infection. Sometimes, they may send the sample to a laboratory for further tests.

Most people won’t need any further tests. But sometimes your GP may recommend further tests to check for any underlying problems, especially if your cystitis keeps coming back. Tests may include:

- an ultrasound scan – this uses soundwaves to create an image of the inside of your body

- a cystoscopy – this is a test to look inside your bladder and urinary tract using a thin tube inserted into your urethra

If you have symptoms of cystitis but you don’t have signs of a bacterial infection, you may have interstitial cystitis. Interstitial cystitis is difficult to diagnose and treat, so your GP may refer you to a specialist for further investigation.

Self-help measures for cystitis

Mild cystitis may clear up by itself after a few days without any specific treatment. In the meantime, you can try the following to ease your symptoms.

- Take over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol and ibuprofen to help with any pain.

- Drink enough fluids to keep hydrated.

- Don’t drink too much strong tea or coffee, alcohol, or acidic drinks (like fruit juices and fizzy drinks). These may make your symptoms worse.

You can buy cystitis remedies over the counter from a pharmacy. These aim to make your urine less acidic and reduce the burning or discomfort when you pee. But there’s no evidence that these products work. If you do decide to try them, check with your pharmacist or GP first. You may not be able to use them if you’re pregnant, on a low-salt diet or have heart, liver, or kidney problems.

There’s no evidence that cranberry drinks or products help relieve cystitis symptoms.

Need a GP appointment? Telephone or Video GP service

With our GP services, we aim to give you an appointment the same day, subject to availability.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0343 253 8381∧

Cystitis treatment

If your symptoms haven’t cleared on their own, your GP may prescribe antibiotics. Sometimes you may have a delayed prescription. This means you only start the antibiotics if your symptoms don’t get better within 48 hours or if they start getting worse.

You usually take antibiotics for cystitis for three days, but sometimes they’re prescribed for seven days or longer. Your symptoms should start to ease after a couple of days of taking antibiotics. If they don’t, you should see your GP again. Your GP may send a sample of your urine to a laboratory to check which bacteria are causing your symptoms. They may then prescribe a different antibiotic.

It’s important to take the whole course of antibiotics, even if your symptoms seem to have cleared up. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine. If you have any questions, ask your pharmacist or GP for advice.

If your cystitis comes back or the antibiotics still aren’t working, see your GP. They may refer you to a urologist (a doctor who specialises in the urinary system) for more tests.

Complications of cystitis

Cystitis is usually mild and doesn’t cause any further problems. But in some people, it can be harder to get rid of or more likely to cause complications. Certain things can make you more likely to develop complicated cystitis. These include:

- being pregnant

- being older

- getting cystitis from a catheter

- having conditions that affect the structure or your urinary tract or how it works

- having conditions affecting your immune system, like diabetes

The most common complication is when bacteria from your bladder travel up to your kidneys. This causes a kidney infection(pyelonephritis). Symptoms can include pain in your side and back and a high temperature (fever). You may feel sick (or be sick) too. Pyelonephritis can be treated with antibiotics. If it isn’t treated, it may damage your kidneys.

If you’re pregnant, untreated pyelonephritis can cause you to give birth early or to have a baby with a low birth weight. You’ll be screened for cystitis at your early antenatal appointments. This means if you have it, it can be treated quickly with antibiotics and reduce your risk of pyelonephritis.

If you have male sex organs, cystitis may lead to an infection of your prostate gland (prostatitis). This can cause pain, especially at the bottom of your penis and around your anus (back passage). You may have difficulties passing urine. Prostatitis is treated with antibiotics.

Prevention of cystitis

If you keep getting cystitis, your doctor may give you some advice on things you can do to reduce the risk of it coming back. There is limited evidence for most of these things, but you may find they help. They include the following.

- Drink enough fluids to keep hydrated.

- Wear underwear that’s made from natural materials, such as cotton or linen.

- Wipe from front to back after doing a poo.

- Always pee as soon as you feel you need to go – don’t put it off.

- Go for a pee as soon as you can after sex.

- If you’ve been through the menopause, consider using oestrogen replacement vaginal creams and gels.

- Try not to use spermicide-coated condoms or diaphragms.

Talk to your GP or practice nurse about the most appropriate contraception for you if you keep getting cystitis.

Some people find that cranberry drinks or products, or taking a substance called D-mannose helps to prevent cystitis if they’re prone to it. There’s some evidence that cranberry products can help prevent attacks in some people who get regular cystitis. But there’s not a lot of evidence for D-mannose. If you’re pregnant, check with a pharmacist or your GP before taking these products.

Antibiotics to prevent cystitis

If you’ve tried the measures above and they aren’t helping, your GP may suggest taking antibiotics to prevent cystitis. This may be:

- a single dose to take when you’re exposed to something that usually triggers cystitis for you (for example, having sex)

- if this doesn’t help, a daily antibiotic to take

You’ll usually be prescribed trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin if you’re taking antibiotics to prevent cystitis. There are potential side-effects and risks to taking antibiotics regularly or long-term. Your doctor will discuss these with you.

Cystitis isn’t a sexually transmitted infection (STI). But the bacteria that cause it can get into your bladder when you have sex.

Some STIs, such as chlamydia, can cause similar symptoms to cystitis. If an STI is a possibility, it’s important to get checked out at a sexual health clinic or by your GP.

The main symptoms of cystitis include burning or discomfort when you pee and needing to pee more regularly. This can include at night. You may have a strong urge to pee, and your pee may appear cloudy. Find out more in our section on symptoms.

Cystitis usually goes away by itself after a few days. If it doesn’t, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics to help get rid of it. You usually take these for between three and seven days. See our section on treatment to find out more.

You don’t always need to see a doctor for cystitis. If your symptoms are mild, you may be able to wait to see if they clear by themselves. There are some other circumstances when you should always see a doctor, including if you’re pregnant or if you feel very unwell. Find out more in our section on symptoms.

If you keep getting cystitis, it may help to make a few changes. Make sure you’re drinking enough fluids. It may also help to make sure you wipe from front to back after doing a poo. Don’t hold off going for a pee when you need to, or after sex. Talk to your doctor about other possible options. See our section on prevention to find out more.

Did our Cystitis information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Urinary tract infection (lower) – women. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised March 2023

- Urinary tract. NCI dictionary of cancer terms. National Cancer Institute. www.cancer.gov, accessed 5 April 2023

- Li R, Leslie SW. Cystitis. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 6 January 2023

- Acute cystitis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 6 March 2023

- Urinary tract infection in adults. Patient. patient.info, last edited 31 March 2023

- Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Patient. patient.info, last edited 22 June 2021

- Urinary tract infection in pregnancy. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, last review/revision Oct 2021

- Urinary tract infection in children. Patient. patient.info, last edited August 2022

- Bacterial urinary tract infections. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, last review/revision July 2021

- Conditions for which over the counter items should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: Guidance for CCGs. NHS England, 29 March 2018. www.england.nhs.uk

- Thornley T, Kirkdale CL, Beech E, et al. Evaluation of a community pharmacy-led test-and-treat service for women with uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in England. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2020; 2(1):dlaa010. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlaa010

- Urinary tract infections in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). nice.org.uk, last updated 15 February 2023

- Engelsgjerd JS, Deibert CM. Cystoscopy. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 17 July 2022

- Self-help information for women with recurrent cystitis. The British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, published June 2020

- Urinary infection (adult). The British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, accessed 6 April 2023

- Urological pain. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 6 March 2023

- Sodium bicarbonate. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 6 March 2023

- Pyelonephritis. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed 20 January 2022

- Prostatitis – acute. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised August 2021

- EAU guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology. uroweb.org, published 2023

- Urinary tract infection (recurrent): antimicrobial prescribing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). nice.org.uk, published 31 October 2018

- Williams G, Hahn D, Stephens JH, et al. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023, Issue 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub6

- Chlamydia – uncomplicated genital. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised April 2022