Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism)

Your health experts: Dr Amilia Alifrangis, Lead Physician at Bupa Health Clinics and Dr Raja N R Padidela, Consultant in Paediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, September 2023

Next review due December 2026

Overactive thyroid means your thyroid gland is making too much thyroid hormone. This is also known as hyperthyroidism or thyrotoxicosis. If you have an overactive thyroid, you may feel weak and tired, anxious or irritable, and lose weight. Treatment can lower your thyroid hormone levels and usually ease your symptoms.

About overactive thyroid

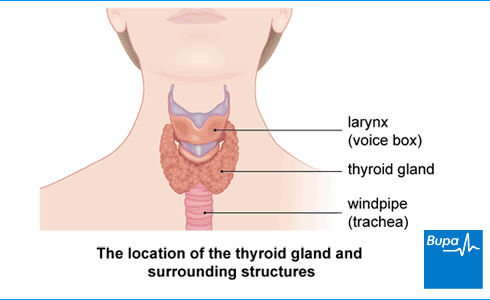

Your thyroid gland is in your neck, in front of your windpipe. It produces two hormones:

- thyroxine (T4)

- triiodothyronine (T3)

Thyroid hormones affect tissues throughout your body and help to control your metabolism. Your metabolism is the combination of all the chemical processes that happen in your body, and include those that change the food you eat into energy. Too much thyroid hormone speeds up your body’s metabolism. When your metabolism speeds up, you may lose weight even if you eat more, and have other symptoms, such as a fast heart rate.

Causes of overactive thyroid

Lots of things can cause an overactive thyroid. The most common cause is a condition called Graves’ disease, which is an autoimmune disease. This means that your body mistakenly attacks your thyroid gland and it responds by producing too much hormone. Other causes of an overactive thyroid include:

- conditions that produce swellings (nodules) on your thyroid gland

- thyroiditis, which is inflammation of your thyroid gland, sometimes caused by a viral infection

- taking some medicines – for example, amiodarone and lithium

Some things can increase your risk of getting an overactive thyroid. These include if you:

- have a family member with Graves’ disease

- smoke

- are a woman – women are 10 times more likely to develop an overactive thyroid compared with men

Symptoms of overactive thyroid

Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) symptoms can vary – you might just have mild symptoms or they may be severe. Your symptoms can depend on your age and on what’s causing your overactive thyroid. How bad your symptoms are doesn’t always reflect how high your thyroid hormones are. For example, you may feel fairly well even if your thyroid hormones are quite high.

The main overactive thyroid symptoms include:

- feeling tired with weak muscles

- feeling hot and less able to cope with heat

- losing (or sometimes gaining) weight without intending to

- feeling hungry and eating more than is usual for you

- diarrhoea

- sweating more than usual

- feeling emotionally up and down, restless and irritable

- a feeling of pressure in your neck or difficulty swallowing

- a swelling or a lump in the front of your neck (this is called a goitre and can be caused by a large thyroid gland)

- anxiety

- shaking (tremors)

- a fast or irregular heart rate (palpitations)

- feeling breathless

- losing your hair, which may become generally sparse (it will usually grow back with treatment)

- in women, irregular or no periods

- in men, less interest in having sex (a reduced libido) and swollen breast tissue (gynaecomastia)

If you have any of these hyperthyroidism symptoms, contact a GP.

Some people with overactive thyroid have problems with their eyes. For more information, see our FAQ: Can an overactive thyroid gland cause eye problems?

Diagnosis of overactive thyroid

The GP will ask about your symptoms and medical history, and will examine you. They’ll ask if anyone in your family has an overactive thyroid gland.

You may need to have one or more blood tests to check the level of thyroid hormones in your body. The main hormones measured in blood tests are:

- TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), which is made by your pituitary gland to control your thyroid gland

- FT4 – free T4 (the active part of thyroxine)

- FT3 – free T3 (the active part of triiodothyronine)

You may hear these blood tests referred to as ‘thyroid function tests’. The GP will explain what they mean in more detail.

If you have an overactive thyroid, you’ll have a low TSH level with a high FT4 level and a high FT3 level.

If the results of the blood tests show you have an overactive thyroid, the GP will refer you to see a specialist. This will be an endocrinologist, a doctor who specialises in treating hormone problems, such as thyroid conditions.

GP Subscriptions – Access a GP whenever you need one for less than £20 per month

You can’t predict when you might want to see a GP, but you can be ready for when you do. Our GP subscriptions are available to anyone over 18 and give you peace of mind, with 15-minute appointments when it suits you at no extra cost.

Treatment of overactive thyroid

Treatment of an overactive thyroid depends on what has caused it and how severe your symptoms are. Any overactive thyroid treatment you have will aim to lower your thyroid hormones levels, ease your symptoms and prevent complications.

The three main treatments for an overactive thyroid are:

- medicines

- radioactive iodine

- surgery

Ask your doctor to explain which is the best option for you.

Medicines

When you’re first diagnosed with an overactive thyroid, your doctor may offer you antithyroid drugs, either carbimazole or propylthiouracil. These help to reduce the amount of hormone your thyroid gland produces.

These medicines usually work quite quickly but it may be two to three weeks until you get the full benefit. You’ll need to take these medicines for 12 to 18 months. You may be able to stop taking them but your symptoms may come back if you stop. If this happens, you may need to try a different treatment.

Your doctor may also recommend that you take beta-blockers for symptoms, such as a fast heartbeat (palpitations) or shaking. You may need to take these until your thyroid hormone levels come down.

Read the patient information that comes with your medicines carefully. This will give you information about possible side-effects and what you should do if you get them. If you have any questions about your medicine, ask your doctor.

Medicines for overactive thyroid and pregnancy

If you’re taking medicine for an overactive thyroid and you want to get pregnant, speak to your doctor. If at all possible, it’s best to plan your pregnancy and work with your doctor to manage your thyroid levels.

Your doctor may recommend a change to your medicine while you’re trying to get pregnant and during your first trimester (the first three months of your pregnancy). This is to make sure your baby has the fewest possible effects from your medicine.

Radioiodine treatment

Radioactive iodine aims to destroy tissue in your thyroid gland so that it produces fewer hormones. You take radioactive iodine as a drink. It takes around three to four months to work fully. Only your thyroid gland takes up the radioactive iodine, so it doesn’t harm other parts of your body.

You can’t have radioactive iodine treatment if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding. You should also use contraception for at least six months after your treatment. For more information about precautions you should take after radioactive iodine treatment, see our FAQs.

After radioactive iodine treatment, most people won’t be able to make enough of the thyroid hormone their body needs to stay healthy. This is called hypothyroidism. So, if you’ve had radioactive iodine treatment, you may need to take replacement thyroid hormone (levothyroxine) for the rest of your life.

Surgery

Another option to treat an overactive thyroid is to have all or most of your thyroid gland removed. Your doctor may suggest surgery if:

- medicines and radioactive iodine treatments haven’t worked or you can’t take them

- you have a very large goitre (swollen thyroid gland), which is putting pressure on your neck

- you’re pregnant and unwilling or unable to take medicines

- you have thyroid eye disease, because radioiodine treatment can make this worse

After the operation, depending on how much of your thyroid gland was removed, your body may not produce enough thyroid hormones. This means you might need to take replacement thyroid hormone (levothyroxine) for the rest of your life.

Monitoring your thyroid levels

During and after treatment for an overactive thyroid, you may need to have regular blood tests and check-ups. This is to measure the amount of thyroid hormones in your body and to check that treatment has worked. It’s important to make sure that your thyroid hormone levels don’t become too low because you could develop hypothyroidism. This is when you don’t have enough thyroid hormone in your body.

How often you’ll need these tests will depend on what caused your condition and what treatment you had. Your doctor will explain what you need to do.

Complications of overactive thyroid

Most people with an overactive thyroid recover well after treatment. But some people may develop complications, some of which can be serious or life-threatening. The main complications of an overactive thyroid are listed below.

- Heart problems, such as heart failure or an irregular and fast heartbeat (atrial fibrillation).

- Sight problems – if you have Graves’ disease, you may develop a condition called thyroid eye disease – see our FAQ section for more information.

- Thyroid storm – this is a severe condition that needs emergency treatment. The symptoms include a fever, heart problems and restlessness.

- If you’re pregnant, an uncontrolled overactive thyroid could affect your baby. They may be born early or underweight, for example. An overactive thyroid can also lead to miscarriage. Tell your doctor if you’re planning a baby or think you might be pregnant.

The most common cause of an overactive thyroid is a condition called Graves’ disease, which is an autoimmune disease. This means that your body mistakenly attacks your thyroid gland and it responds by producing too much hormone. Other causes of an overactive thyroid include thyroiditis, which is inflammation of your thyroid gland sometimes, which can be caused by a viral infection.

See our section on causes of overactive thyroid for more information.

Yes, it may be possible to fix an overactive thyroid. The treatment you have to do this will depend on what’s caused your overactive thyroid and how bad your symptoms are. But it will aim to lower your thyroid hormone levels, ease your symptoms and prevent complications.

See our section on treatment of overactive thyroid for more information.

While your body gets rid of the radioactive iodine, you’ll need to take precautions to keep others safe. Radioactive iodine leaves your body in your urine, sweat, and saliva. For three weeks, limit your contact with babies, young children and pregnant women and stay away from crowded places where you’d be close to others for a long time. And don’t share a bed or prepare food for others.

See our section on treatment of overactive thyroid for more information on radioactive iodine treatment.

If you have an overactive thyroid caused by Graves’ disease, you could develop problems with your eyes. Around a quarter of all people with Graves’ disease develop Graves’ ophthalmopathy, or thyroid eye disease. The main symptoms include bulging or staring eyes, swollen and red eyelids and watery eyes. If you have any of these symptoms, see a GP as soon as you can.

If you have an overactive thyroid, it can affect your ability to get pregnant. Some thyroid conditions can cause you to have irregular periods and stop your ovaries producing eggs (ovulation). This can make it difficult to get pregnant.

You don’t need to follow any special diet if you have an overactive thyroid, just aim to eat healthily. After treatment for an overactive thyroid, you might want to consider what and how much you eat. After your treatment, you may need to change your lifestyle by increasing your activities and watching what you eat to avoid putting on weight.

Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism)

If you have an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism), it means your thyroid gland isn’t producing enough thyroid hormones.

Portion size guide

Find out more about the recommended portion sizes for the key food groups that will meet your nutritional and energy requirements.

Tips for a healthy and well-balanced diet

A healthy, well-balanced diet involves eating foods from a variety of food groups to get the nutrients that your body needs to function.

Beta-blockers

Other helpful websites

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Hyperthyroidism. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised January 2021

- Hyperthyroidism. Patient. patient.info, last edited 26 February 2020

- Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. www.niddk.nih.gov, last reviewed August 2021

- Hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 8 February 2022

- Metabolism. Encyclopaedia Britannica. www.britannica.com, last updated 20 March 2023

- Pirahanchi Y, Tariq MA, Jialal I. Physiology, thyroid. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 13 February 2023

- Mathew P, Kaur J, Rawla P. Hyperthyroidism. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 19 March 2023

- Hyperthyroidism. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 6 March 2023

- Thyroid disease: assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 20 November 2019

- Hair loss and thyroid disorders. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, accessed 27 March 2023

- Graves' disease. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 27 February 2023

- Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Patient. patient.info, last edited 4 March 2020

- Your guide to treatment of an overactive or enlarged thyroid gland with radioactive iodine. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, revised 2022

- Radioactive iodine treatment for hyperthyroidism. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, accessed 28 March 2023

- After radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 24 May 2021

- Your guide to pregnancy and fertility in thyroid disorders. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, revised 2021

- Endometriosis. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised February 2020

- Polycystic ovary syndrome. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised February 2022

- Thyroid and diet factsheet. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, accessed 28 March 2023

- Hyperthyroidism. British Thyroid Foundation. www.btf-thyroid.org, revised 2018