Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

Your health expert: Mr Damian McClelland, Trauma and Orthopaedic Consultant, and Clinical Director for Musculoskeletal Services at Bupa

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor, June 2023

Next review due June 2026

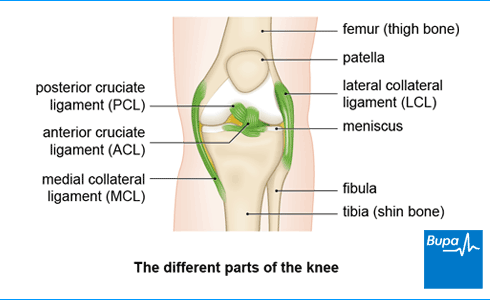

A posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury is when you damage one of the ligaments inside your knee. Your PCL connects your thigh bone (femur) to the back of your shin bone (tibia). A PCL injury can be a partial or complete tear of the ligament or a stretched ligament.

About posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

Your posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) passes behind another ligament, the anterior cruciate ligament(ACL). The cruciate ligaments get their name from the fact they form a cross shape within the knee because they run in different directions from the thigh to the shin bone. Along with the other ligaments in your knee, your PCL keeps your knee stable and prevents your thigh and shin bones from moving out of place.

When your knee ligament is stretched but still intact, this is called a PCL sprain. Sprains are given different grades depending on how severe they are. Usually, if you injure your PCL, you’ll also have injuries to other parts of your knee such as your medial collateral ligament or ACL.

Causes of posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

It usually takes quite a powerful force to injure your posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). It’s often caused by a direct blow to the front of your knee when it’s bent, which extends it beyond the normal range of movement. This can happen if you:

- fall forward onto a bent knee

- have a car accident and hit your knees on the dashboard, which can tear your PCL

- are playing sport and have a direct blow to your knee from a collision with another player

Symptoms of a posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury symptoms can vary. You may have few symptoms at first, and may not even notice that you’ve damaged your PCL. But your knee will probably swell and you may get some pain around the back of your knee, especially when you kneel. And you might not be able to move it as fully as before. You’ll probably still be able to walk normally afterwards but it may feel different due to the swelling. Sometimes your knee can feel unstable.

If your PCL injury goes untreated for some time, your knee may start to feel sore, particularly at the front. You may begin to find it uncomfortable going down an incline – for example, while walking or running downhill or going down stairs. You may also have discomfort when you start to run, if you lift a heavy weight or if you walk longer distances.

It’s common to injure other ligaments, or other parts of your knee at the same time as your PCL. Together, these may cause general symptoms of pain and swelling in your knee.

Self-help for posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

It’s a good idea to follow the POLICE procedure after a posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury. POLICE stands for the following.

Protect. Protect your injury from further damage. Rest immediately after the injury but not for long. Consider using some form of support or crutches.

Optimal Loading. Get active sooner rather than later. Start to put weight on your knee and build up your range of movement. Do this gradually – be guided by what feels right for you.

Ice. Place a cold compress such as a bag of ice or frozen peas wrapped in a towel onto your knee. Do this for around 20 minutes every couple of hours for the first two to three days.

Compression. Compress your knee using a bandage to help reduce swelling.

Elevation. Elevate your knee above the level of your heart to reduce swelling. Sit or lie on a chair and use a cushion to raise your leg.

Infographic: POLICE principles

Bupa's POLICE infographic (PDF, 0.5 MB) below illustrates the ‘POLICE principles’ to reduce your pain and help you to recover.

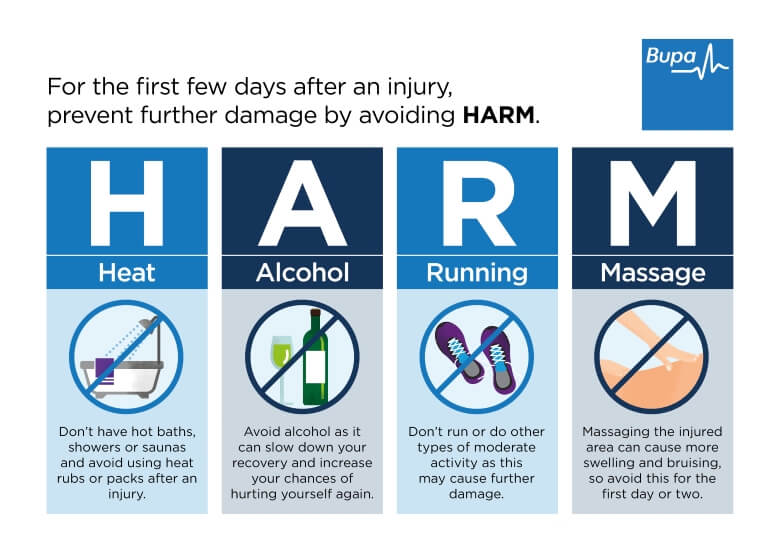

And there are certain things you should avoid in the first three days after your injury so you don’t damage your knee further. These can be remembered as HARM, which stands for the following.

Heat. Don’t have hot baths, showers or saunas, and avoid heat packs and rubs.

Alcohol. Drinking alcohol can slow down your recovery and mask your symptoms – increasing the risk that you’ll injure yourself again.

Running. Don’t run or do any other form of moderate exercise.

Massage. Massaging the affected areas can cause more swelling and damage, so avoid this for the first day or two.

Infographic: HARM principle

Bupa's HARM infographic (PDF, 0.6 MB) below illustrates the ‘HARM principle' of things you should avoid doing in the first three days after your injury.

Both POLICE and HARM are self-help measures you can take to treat any type of soft tissue injury to your knee, including a PCL injury.

If you’re finding it difficult to put weight on your knee, you may need to use crutches or wear a brace to support you for a while. Your doctor or physiotherapist will explain how long you’ll need to use these for.

Treatment of posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

If you’re worried that you've injured your knee, contact a medical professional who can examine it for you. They may suggest you have X-rays of your knee. They may then refer you to an acute knee clinic, which will organise any investigations such as an MRI scan, and any further treatment you may need.

Your PCL injury treatment will depend on several things. These include how severe the damage is, whether other parts of your knee are also injured, and how well you respond to treatment. The initial treatment is to control your pain and swelling using the POLICE and HARM self-help measures (see our section on self-help). Further treatments to help you recover include physiotherapy, medicines and surgery.

You may see an orthopaedic surgeon (a doctor who specialises in bone surgery) or a sports medicine professional, such as a sports doctor or a physiotherapist. There are different PCL injury treatments that your doctor or physiotherapist may suggest, and a lot that you can do yourself to help you recover.

Medicines

You can take over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen to help relieve your pain. As well as easing your pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen may help to reduce inflammation and swelling. Your doctor may prescribe stronger painkillers if your knee is really painful. Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine, and if you have questions, ask a pharmacist or GP for advice.

Physiotherapy

A physiotherapist will carefully assess your knee and plan a programme of rehabilitation exercises to suit your individual needs. Exercises to strengthen your thigh muscles (quadriceps) are especially important after PCL injuries. Make sure you do the exercises because this is an important part of your recovery. The aim of physiotherapy is to help your knee recover its full range of movement and its strength and stability.

How long it takes to recover can vary – you may need physiotherapy for anything from two to 12 weeks initially. You might then need to continue doing exercises for up to year but ask your physio for advice.

Surgery

Most people with a PCL sprain recover with physiotherapy alone and don’t need to have an operation. But in some situations, surgery may be the best option to repair the injury to your PCL. This is most likely if:

- you’ve damaged more than one ligament or tissue in your knee

- your knee remains unstable or painful after physiotherapy

You should be able to return to your normal activities, including sports, within nine months to a year after your operation for a torn PCL. But check with your surgeon because this may vary. After surgery, you’ll need to follow a course of physiotherapy to build the strength up in your thigh muscles.

Ask your doctor about the benefits and risks of surgery, and how it might help you.

Looking for physiotherapy?

You can access a range of treatments on a pay as you go basis, including physiotherapy.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0370 218 6528∧

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury

An ACL injury can be a partial or a complete tear, an overstretch, or a detachment of the ligament.

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury

An LCL injury is often associated with injuries to the ligaments and tendons in this area, as well as to other parts of the knee.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury

The MCL is the most commonly injured knee ligament. It often gets injured during sports such as rugby.

Meniscal tear

Tears of the menisci are a common injury. When people talk about a ‘torn cartilage’ in their knee they usually mean a meniscus injury.

Patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee)

Patellar tendinopathy is also called ‘jumper’s knee’ because the injury commonly occurs during sports that involve jumping, such as basketball.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is sometimes called ‘runner’s knee’ because it’s particularly common in people who run or do other sports.

Did our Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Knee ligament injuries. Patient. patient.info, last edited 16 August 2022

- Raj MA, Mabrouk A, Varacallo M. Posterior cruciate ligament knee injuries. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, last updated 25 September 2022

- Posterior cruciate ligament injury. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 11 August 2022

- Knee pain – assessment. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised August 2022

- Bezuglov E, Khaitin V, Shoshorina M, et al. Sport-specific rehabilitation, but not PRP injections, might reduce the re-injury rate of muscle injuries in professional soccer players: A retrospective cohort study. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2022; 7(4):72. doi: 10.3390/jfmk7040072

- Naqvi U, Sherman AL. Medial collateral ligament knee injuries. StatPearls publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, last update 19 July 2022

- Sprains and strains. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised September 2020