Plantar fasciitis (heel pain)

Your health expert: Mr Jonathan Larholt, Consultant Podiatric Surgeon

Content editor review by Pippa Coulter, Freelance Health Editor, September 2023

Next review due September 2026

Plantar fasciitis is a common cause of heel pain. It can take up to 12 months for plantar fasciitis heel pain to completely go. But in the meantime, there are several things you can do to reduce your pain and help your plantar fascia to heal.

About plantar fasciitis

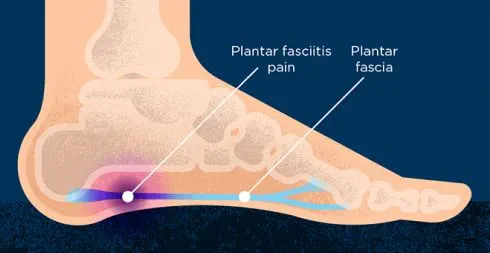

Plantar fasciitis affects the area of your foot known as the plantar fascia. This is a thick band of tissue that runs along the sole of your foot. It starts in your heel, runs along the arch of your foot, and fans out to connect with the base of each toe. It stabilises your foot when you’re walking and acts as a shock absorber.

In plantar fasciitis, your plantar fascia becomes damaged with lots of tiny tears. It’s known as an overuse injury because it’s usually due to repeated stress on the area over time. The area nearest to the heel is most likely to be damaged.

Plantar fasciitis is common in people who run regularly. But it can affect anyone. It’s most common in people between the ages of 40 and 60. Around one in three people who get it have it in both feet.

Causes of plantar fasciitis

You can get plantar fasciitis if there is too much pressure on the band of tissue that runs along the sole of your foot. The following factors can increase your risk.

- Being overweight or obese.

- Having high arches in your feet or being flat-footed.

- Doing regular high-impact activities such as running – or suddenly increasing how much of these activities you do.

- Spending a lot of time on your feet. For example, having a job where you’re standing or walking around all day.

- Wearing poorly fitting, worn-out, or unsupportive shoes or trainers.

- Having tight leg muscles or a tight Achilles tendon (the tendon that runs from your heel up the back of your leg). This can affect how you walk and move your foot.

- Having certain types of inflammatory arthritis such as psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Symptoms of plantar fasciitis

The main symptom of plantar fasciitis is pain in your heel. Sometimes, it may spread into the arch of your foot. Plantar fasciitis pain:

- is often described as being a sharp, stabbing pain

- is often worse when you take your first steps after waking up or being inactive

- can be brought on by walking, standing, or running for a long time

- may gradually lessen as you start to move around, but increases throughout the day

- might feel worse if you’re walking barefoot, on your toes, or going up stairs

- usually feels better if you rest your foot

You can often manage plantar fasciitis pain yourself without needing to see a healthcare professional. For more information, see our section on self-help. But if your symptoms are so severe that you’re finding it difficult to do anything, see your GP or a footcare specialist. This might be a podiatrist or a physiotherapist. It’s also worth seeing a professional if your symptoms aren’t getting better within a couple weeks of trying self-care measures.

You can often book an appointment with an NHS podiatrist or physiotherapist without needing to go through your GP. This is known as self-referral. If this is unavailable in your area, see your GP for advice. They can refer you if necessary. You can also pay to see a podiatrist or physiotherapist privately.

Diagnosis of plantar fasciitis

A podiatrist, physiotherapist, or GP can diagnose plantar fasciitis. They’ll usually be able to diagnose it from your symptoms and by looking at your foot. They will ask about your general health and activity, and when you usually notice your symptoms.

The health professional will feel and press on different areas of your foot and ankle to see where it’s painful. They may gently lift your big toe. This can be painful if you have plantar fasciitis. They may also ask you to move your foot up and down, walk around or stand on your toes to see if this brings on any pain.

They may ask to weigh you and take your height. This is to check your body mass index (BMI), in case your weight is a factor.

If it’s unclear whether your symptoms are due to plantar fasciitis, your GP may refer you to a podiatric or orthopaedic surgeon. They may recommend tests to rule out other causes of your heel pain. These can include an X-ray, MRI, or ultrasound. You don’t usually need further tests or scans to diagnose plantar fasciitis.

Self-help for plantar fasciitis

The following tips can help to relieve your pain and encourage your foot to heal.

- Rest your foot as much as possible. Avoid standing or walking for long periods and cut down or stop any activity that triggers your pain.

- If you’re a runner, try switching to a lower-impact exercise (such as swimming or cycling) while your foot heals. You can also try running on a softer surface.

- Try doing some exercises to stretch your plantar fascia, calf muscles, and Achilles tendon. We describe some below. You should aim to do these at least twice a day.

- Apply ice (wrapped in a towel) to the area when it’s painful. You can do this for up to 20 minutes, two or three times a day.

- Make sure you’re wearing shoes with good support and cushioned heels. Laced sports shoes are a good option. Replace shoes when they’re worn out.

- Use insoles and heel pads in your shoes to help provide support. Your podiatrist, physiotherapist, or pharmacist may be able to recommend some.

- Avoid high heels, flip-flops, flat shoes, and backless shoes. Don’t walk barefoot.

- If you’re overweight, aim to lose the excess weight.

- Use over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol and ibuprofen to help manage your pain.

Most people recover within about a year if they follow these measures. It can be quicker than this. But it usually takes at least six to eight weeks to see any improvement in your symptoms.

Stretches and exercises for plantar fasciitis

Stretches for plantar fasciitis can help to reduce pain and prevent further damage. You can do these stretches yourself at home. It’s a good idea to do them at least twice a day. A podiatrist or physiotherapist can give you more advice about how to do the exercises.

Achilles tendon and plantar fascia stretch

Loop a long towel or strap around the ball of your foot. Pull your toes towards your body, while keeping your leg straight. Hold for 30 seconds. Repeat this three times for each foot.

Wall push

Stand facing a wall, with one foot in front of the other. Your feet should be shoulder width apart and facing the wall, with your front knee bent and your back knee straight.

Place both your hands on the wall at shoulder height. Lean towards the wall by bending your front knee. You’ll feel the stretch through your calf in the back leg. Hold for 30 to 45 seconds, then relax. Repeat three to four times.

The further your back leg is from the wall, the greater the stretch. So, start close to the wall and gradually move your back leg further way from the wall as you get used to the exercise.

Stair stretch

Stand on a stair, facing upstairs and holding onto the rail for support. Position your feet so that your heels hang over the end of the step, and your legs are slightly apart. Lower your heels until you feel tightening in your calves. Hold this position for 20 to 60 seconds, then relax. Repeat six times.

Plantar fascia stretch

While you’re sitting down, roll your foot over a round object such as a rolling pin, drinks can or tennis ball. Allow your foot and ankle to move in all directions. Carry on for a few minutes or until you feel discomfort.

Sitting plantar fascia stretch

Sit down and cross one foot over your knee. Then, grab the base of your toes and pull them back towards your body. Hold this position for 15 to 20 seconds and repeat three times.

Treatment of plantar fasciitis

A podiatrist, physiotherapist, or GP can help with plantar fasciitis. They will usually recommend self-help measures and stretching exercises first. A podiatrist or physiotherapist can go through these with you to make sure you’re doing them correctly.

A physiotherapist may use other techniques aimed at helping with pain relief. These may include massage, ultrasound, and laser therapy.

Foot supports and splints

A podiatrist can advise on suitable footwear and supports in your shoes that could help. They may also recommend some other things to try such as the following.

- Custom-made orthoses such as insoles or heel or arch supports.

- Taping your foot. This involves applying athletic tape to the sole of your foot and around your heel. It’s normally left in place for three to five days.

- Night splints. These help to keep your foot pointing upwards and your toes extended while you sleep. This gently stretches your plantar fascia and can help it to heal faster.

Steroid injection

If your symptoms are making it hard to do your usual activities, you may be able to have a steroid injection. A steroid injection may help to give you some short-term pain relief. But it doesn’t always last for long – the pain can return within a month. The injection is often quite painful, and there is a small risk of complications. But some people do find it worthwhile, especially if they need immediate pain relief. If it helps, you can have a second injection, with at least six weeks between injections.

When possible, the injection is done under ultrasound. This helps to guide it into the right place. Your health professional will help you to weigh up the pros and cons of having a steroid injection before you decide whether to have one.

Specialist treatments

Your GP may refer you to a surgeon if your symptoms haven’t improved after 6 to 12 months. They may offer you the following treatments.

- Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT). This involves passing shockwaves through the affected area. ESWT is thought to be a safe alternative to steroid injections, and you may find it helpful.

- Surgery on your foot to release your plantar fascia. This can help to relieve pain if other treatments haven’t helped. But there are certain risks involved. And if you’ve had the condition for longer than two years, this may be less likely to help.

Your surgeon will tell you if these treatments may be suitable for you.

Physiotherapy services

Our evidence-based physiotherapy services are designed to address a wide range of musculoskeletal conditions, promote recovery, and enhance overall quality of life. Our physiotherapists are specialised in treating orthopaedic, rheumatological, musculoskeletal conditions and sports-related injury by using tools including education and advice, pain management strategies, exercise therapy and manual therapy techniques.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0345 850 8399

Prevention of plantar fasciitis

There are several things you can do to reduce your risk of developing plantar fasciitis.

- Wear well-fitting footwear with good cushioning in the heels and arch support.

- Replace trainers or shoes as soon as they’re worn out.

- Avoid exercising on a hard surface.

- Do regular stretches involving your plantar fascia and Achilles tendon, especially before and after exercise.

- Lose weight if you’re overweight.

Plantar fasciitis causes pain on the underside of your heel. It’s often a sharp, stabbing pain, and can sometimes spread into the arch of your foot. It’s often worse if you’ve been inactive for a while and improves when you start moving around. Find out more in our symptoms section.

Plantar fasciitis will usually go away eventually. Most people find they recover within a year if they follow self-help measures. It’s not this long for everyone, but it usually takes at least six to eight weeks until you’ll notice any improvement. Read our self-help section to find out more.

Anything that causes pressure on your feet can lead to plantar fasciitis. High-impact activities like running are major causes. Other things that increase your risk include being overweight, having high arches or flat feet, and spending a lot of time on your feet. Find out more in our causes section.

It’s best to rest your foot as much as possible and do regular exercises to stretch your plantar fascia. But it can take a year or more to completely get rid of plantar fasciitis. Your GP, podiatrist or physiotherapist may be able to offer a steroid injection if you need immediate pain relief, but this doesn’t last long. For more information on managing your pain, read our sections on self-help and treatment.

Physiotherapy

Steroid joint injections

If you have a painful joint from an injury or arthritis, for example, your doctor may offer you a joint injection of a corticosteroid (steroid) medicine.

How to start running: eight tips for beginners

Other helpful websites

Did our Plantar fasciitis (heel pain) information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Plantar fasciitis. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised March 2020

- Plantar fasciitis. Patient. patient.info, last updated 18 January 2022

- Plantar fasciitis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 4 August 2023

- Plantar fasciitis. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, last updated 30 May 2022

- Foot and ankle pain. Versus Arthritis. www.versusarthritis.org, accessed 5 September 2023

- Plantar fasciitis. Versus Arthritis. www.versusarthritis.org, accessed 4 September 2023

- Find a chartered physiotherapist. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. www.csp.org.uk, last reviewed 24 January 2023

- Exercises for the toes, feet and ankles. Versus Arthritis. www.versusarthritis.org, accessed 5 September 2023

- Personal communication. Mr Jonathan Larholt, Consultant Podiatric Surgeon, 26 September 2023