Kidney stones

- Professor Raj Persad, Consultant Urological Surgeon

Kidney stones (or renal calculi) are hard stones that can form in your kidneys. They usually pass out of your body by themselves in your urine. But how easily they pass and how much pain they cause depends on their size and shape. Sometimes you may need hospital treatment to remove them.

About kidney stones

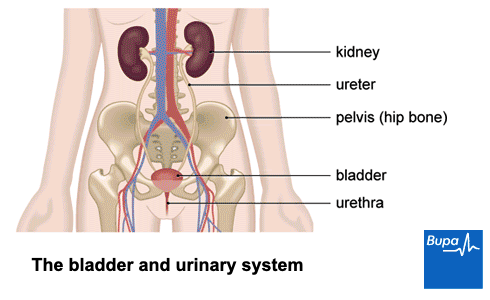

Most people have two kidneys, which ‘clean’ your blood by filtering out water and waste products to make urine. Kidney stones can form when there’s a build-up of salts or minerals in your urine. These minerals form crystals, which are often too small to notice and pass harmlessly out of your body. Sometimes these crystals can build up inside your kidney to form a kidney stone.

Kidney stones are usually made of calcium salts. But they can also be made of other substances including uric acid – a waste product found in your urine. Most stones are less than 2mm but they can be over 2cm.

Some kidney stones stay where they form. But they can move out of your kidney into the tube that carries urine from your kidney to your bladder (the ureter). If they get stuck there, the muscles in the wall of your ureter contract hard to push the stone along. This can cause severe pain, called renal colic (or ureteric colic). Depending on a stone’s size and position, it can stop you passing urine easily and lead to infection.

Up to 1 in 10 people have pain from kidney stones at some point in their life. They’re most common between the ages of 40 and 60 in men, and in the late 20s in women. Men are more likely to develop them than women.

Causes of kidney stones

There are certain factors that can make you more likely to develop kidney stones. These include:

- having a family history of kidney stones

- having medical conditions that affect levels of chemicals in your urine, such as cystinuria, gout, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis and hyperparathyroidism

- your kidneys or ureters being an unusual shape or structure

- having gastrointestinal conditions that affect absorption of nutrients, such as Crohn’s disease or previous surgery

- taking certain medicines or supplements, such as diuretics (water tablets), antacids, vitamin C, calcium or vitamin D supplements

- frequently getting urinary tract infections

- not drinking enough to keep hydrated

- having too much salt, refined sugar, meat or foods that contain oxalate (such as rhubarb, celery, beetroot, spinach and sesame seeds) in your diet

- spending a lot of time in a hot, dry climate

- being very overweight (obese)

- having metabolic syndrome, which means having high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity

Symptoms of kidney stones

Many kidney stones are too small to cause symptoms. They may only be discovered by chance, if you’re having tests for other conditions. But stones can become very painful when they move. Larger stones can also get stuck in your ureter and may cause infection. If you do get kidney stone symptoms, they may include the following.

- Pain or aching on one or both sides of your lower back.

- Sudden waves of severe pain, known as renal colic. This can spread from your lower back to your groin and genital area.

- Blood in your urine.

- Feeling or being sick.

- Needing to pass urine (pee) frequently or very urgently.

- Stinging or burning when you pee.

- Feeling feverish and sweaty.

If you have any symptoms of kidney stones, contact your GP. If you have severe pain and a high temperature, seek urgent medical attention.

Diagnosis of kidney stones

It’s important to see a GP if you’re having symptoms, such as pain in your side or back. There are several different things it could be, so your doctor will want to examine you. They’ll ask about your symptoms and your medical history. They’ll want to know if you’ve ever had kidney stones before. They will check your abdomen (tummy) for any tenderness and areas that are painful. They may take your blood pressure too.

Your GP may ask for a urine sample to test for blood and signs of infection. They may also ask you to have a blood test. This is to check for infection and to measure the levels of minerals that cause kidney stones in your blood. The blood test will also show how well your kidneys are working.

If your GP suspects kidney stones, they’ll arrange for you to have a scan to confirm the diagnosis. This will also allow your doctor to check the size, location and type of kidney stone. You will usually be offered a CT (computed tomography) scan, but you may be offered an ultrasound scan if you’re pregnant.

If tests confirm you have a kidney stone, your GP will refer you to a urologist for further tests and to discuss your treatment options. A urologist is a specialist doctor who diagnoses and treats conditions affecting the urinary system.

Treatment of kidney stones

You may be able to stay at home while your kidney stone passes, and receive any treatment you need as an outpatient. This means you won’t need to stay in hospital. How your kidney stones are managed will depend on several things. These include:

- the size of your stone

- where the stone is

- how likely it is to pass on its own

- how bad your symptoms are

- whether you have any other health problems

There are some circumstances when your doctor may arrange for you to be admitted to hospital for treatment straight away. These include if you have any signs of infection, or you’re dehydrated or unable to pass urine. You will also usually need to be admitted to hospital if you have a condition that affects your kidney.

Pain relief

Passing a kidney stone is often painful. Whatever treatment you have, one of the first things your doctor will do is help to manage your pain. If your pain isn’t too severe, you can take simple over-the-counter painkillers, such as ibuprofen, paracetamol or low-dose codeine. If you need something stronger, your doctor may offer you suppositories (that you insert into your bottom) or injections of painkillers.

Self-management of kidney stones

If your pain is manageable and you don’t have complications, you may be able to wait for your kidney stone to pass in your urine at home. Your doctor will ask you to strain your urine with a tea strainer or filter paper to help catch the kidney stone. Your doctor may send the stone for testing to find out what type it is, to help prevent any more stones.

How long it takes to pass a kidney stone depends on its size and where it is in your urinary system. It may take up to six weeks. To help with passing a kidney stone, make sure you drink plenty of fluids. Your doctor will monitor you and usually arrange to see you again to check whether the stone has passed. If your stone shows no sign of passing within two to three weeks, they may recommend treatment to remove your kidney stone.

Medicines

Depending on the type, size and location of your stone, your GP may be able to offer some medicines to help your kidney stones pass. These may include the following.

- Medical expulsive therapy (MET). These are medicines called alpha-blockers. MET helps the stone pass out in your urine more quickly by relaxing the muscles in the walls of your ureter. Your doctor may suggest it in some cases if your stone is larger than 5mm across, but less than 10mm.

- Alkalinisation therapy. If you have uric acid stones, your specialist may suggest medicines such as potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate to dissolve them. These help by changing the pH of your urine, to make it more alkaline (less acidic).

Kidney stone removal

Your doctor may recommend a procedure to remove your kidney stone if your pain is severe or the stone is unlikely to pass by itself.

If you’re finding it hard to pass urine, your doctor may suggest inserting a stent or nephrostomy tube before your kidney stone procedure. A stent is a hollow tube that reduces pressure on the ureter (the tube your urine passes through). A nephrostomy tube is a catheter that drains urine direct from your kidney. Both will relieve pain as well as easing any blockage.

There are several different procedures to remove kidney stones. Your urologist will advise which one is best for you, depending on the size, type, and position of your kidney stone. They include the following.

- Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). This involves using shock waves to break up the stone into fragments, which can then be passed in your urine.

- Ureteroscopy. This procedure uses a narrow, flexible instrument called a ureteroscope passed up through your urethra. It breaks up the stone with a laser beam.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). This is keyhole surgery using a telescopic instrument called a nephroscope to remove large stones from your kidney or upper ureter. The nephroscope is inserted through a small cut in the skin of your back to reach your kidney. Laser or ultrasound is then used to break up and remove the stone

- Open surgery. This is surgery to open up your abdomen and directly remove any stones. You’ll usually only have it for very large or multiple stones, or when other procedures are unlikely to help or haven’t worked.

GP Subscriptions – Access a GP whenever you need one for less than £20 per month

You can’t predict when you might want to see a GP, but you can be ready for when you do. Our GP subscriptions are available to anyone over 18 and give you peace of mind, with 15-minute appointments when it suits you at no extra cost.

Treating kidney stones with ESWL

Treating kidney stones with ESWL | Watch in 2 minutes

Extracorpreal shock wave lithotripsy (EWSL) is used to break up kidney stones. This video explains the EWSL procedure and how it works.

After treatment

After treatment for kidney stones your doctor will usually want to review you to check all fragments of your stone have been cleared. You may have some tests to work out your risk of developing more kidney stones.

About half of people who have a first kidney stone will get another one within five years. Your doctor may want to monitor you and may advise regular checks to see if further stones are developing. They will also give you advice about how to reduce your risk of further kidney stones. See Prevention section below.

Complications of kidney stones

A kidney stone can block your ureter and stop the flow of urine. If this isn’t treated, it can permanently damage your kidneys. You may need to have a tube (stent) put in to bypass the blockage and drain the trapped urine.

A blocked ureter can also lead to infection, which can be life-threatening without urgent treatment. Signs of an infection may include a fever. It's important to seek medical help straight away. You may need antibiotics through a drip to clear up the infection quickly.

There can be complications after treatment to remove kidney stones. These vary depending on the type of treatment you have, so ask your specialist for more information.

Prevention of kidney stones

There are things you can do to reduce your risk of developing kidney stones. These include:

- making sure you drink enough fluid to keep hydrated

- limiting the amount of salt in your diet

- maintaining a healthy weight

If you’ve already had a kidney stone, your doctor can give you advice on how to prevent kidney stones coming back. They may recommend medicines to reduce your chance of developing another one. Potassium citrate can make your urine more alkaline and stop calcium stones forming. Thiazide diuretics can also be helpful if you also have a raised calcium level in your urine.

Changes to your diet

Your doctor will also advise you to make some changes to your diet after having a kidney stone.

The most important thing is to increase your fluid intake. You should be drinking at least 2.5 to 3 litres a day. This is the same as five to six pint glasses or five to six average-sized water bottles. Keep drinking throughout the day. You can have tea, coffee and alcohol in moderation. But it’s better if most of your fluid is water or squash. It’s better to avoid fizzy drinks. Try adding fresh lemon juice to your water – it acts as a natural stone inhibitor.

Other dietary changes your doctor may advise include the following.

- Reduce the amount of animal protein (mainly meat) you eat.

- Try to include more fruit and vegetables in your diet.

- Cut down on your salt intake – don’t add extra salt to your food and cut down on processed and pre-prepared foods

- Lose weight if you’re obese or overweight. It’s important to keep physically active too.

Depending on the type of stone you’ve had, your doctor may give you some more specific advice on foods to avoid. This may include the following.

- If you have calcium oxalate stones, avoiding foods with high levels of oxalate, including chocolate, tea, coffee, rhubarb, spinach and nuts.

- If you have uric acid stones, avoiding foods high in purines, including liver, kidneys, herrings, sardines, anchovies and poultry skin.

There’s no need to restrict calcium in your diet. In fact, not having enough calcium can make you more likely to develop a stone. It’s best not to take calcium supplements though, so you can maintain the right level in your body from diet alone. If you already take calcium supplements for some other reason, make sure you’re drinking enough fluids to flush the calcium through your kidneys and bladder. For some types of stone, your doctor may also recommend you avoid vitamin D and high-dose vitamin C supplements.

Tips for a healthy and well-balanced diet

A healthy, well-balanced diet involves eating foods from a variety of food groups to get the nutrients that your body needs to function.

Over-the-counter painkillers

Did our Kidney stones information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Nephrolithiasis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 20 August 2022

- Renal or ureteric colic – acute. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised August 2020

- Urolithiasis. Patient. patient.info, last edited 17 September 2021

- Renal medicine and urology. Oxford handbook of general practice. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published online June 2020

- FAQs about stones. Professionals Endourology. The British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, accessed 20 September 2022

- Kidney anatomy. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 29 August 2017

- Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published January 2019

- Kidney stones. The British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, accessed 20 September 2022

- Dietary advice for stone formers. The British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, published October 2021

- EAU guidelines on urolithiasis. European Association of Urology. uroweb.org, published March 2022

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (keyhole surgery for kidney stones). British Association of Urological Surgeons. www.baus.org.uk, published June 2021

- Pippa Coulter, Freelance Health Editor