Acne

Please note, this topic page has gone past its three year review date. We review our content every three years to ensure we meet the highest standards in health information. The review of this page will be live shortly.

Your health expert: Dr Veronique Bataille, Consultant Dermatologist

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, March 2022.

Next review due March 2025.

Acne (acne vulgaris) is a common skin condition that causes spots, and can vary from being mild to severe. Depending on its impact on you, acne can affect your physical, mental, and social wellbeing. There isn’t a cure for acne but there are treatments that can help to ease your symptoms.

About acne

Acne can affect the skin on your face, back, shoulders and chest and shoulders. And acne can cause different types of spots:

- blackheads

- whiteheads

- inflamed spots that look like red bumps (papules), or are yellow in colour (pustules)

- deep spots that contain fluid, called cysts

Acne is very common in teenagers and young adults – about 9 in 10 people aged 12 to 24 have had acne at some point. And it affects about 650 million people worldwide. It’s less common in later life but adults can get acne too. And newborn babies can sometimes get acne in their first six months. If you have acne as a teenager, it often clears up as an adult.

Acne isn’t contagious, so you can’t catch it or pass it on to other people.

Causes of acne

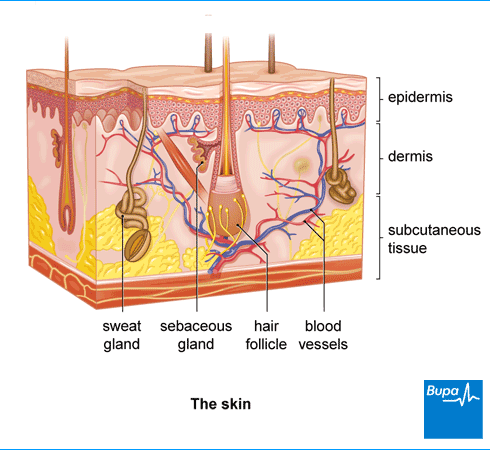

The exact cause of acne isn’t known but if you have acne, you will often have excess sebum (a natural oil) and dead skin cells that block your hair follicles. Changes in your hormones cause your skin to produce more sebum during your teenage years. As a result, your skin becomes greasy and spots develop. Sometimes, a bacterium called Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) that usually lives harmlessly on your skin, can grow inside your hair follicles. It can lead to inflammation (swelling) in spots.

There’s a chance that acne can run in families. Other causes of acne or links to it may include the following.

- Health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome

- Medicines, such as corticosteroids, medicines for epilepsy and lithium (sometimes used to treat depression).

- Hormonal changes. Changes to your hormones just before a period may cause acne to flare up. And if you’re pregnant, you might get acne in your first trimester (the first three months of your pregnancy).

- Cosmetics, which although they don’t cause acne, may make it worse.

Symptoms of acne

The main symptom of acne is spots on your face, chest, back, and shoulders, although you might not have them on all these areas.

The spots can be non-inflamed or inflamed (swollen). Blackheads and whiteheads are non-inflamed spots, and you can also have these if you don’t have acne. Inflamed spots include red bumps and lumps, yellow pus-filled spots or fluid-filled cysts. If you have very severe acne, cysts may join together to form larger, deeper inflamed areas, which are called acne conglobata.

Your skin may look greasy and the spots may feel hot and tender to touch.

You may get one type of spot or a mixture of the different types. How severe acne is can vary from person to person but the following is a guide.

- Mild: you mostly have non-inflamed spots.

- Moderate: you have more spots that are a mixture of inflamed and non-inflamed spots.

- Severe: you have a lot of inflamed spots and cysts that cover a large area of your skin and there are some scars.

Diagnosis of acne

If you think you have acne, go and see a pharmacist. They can recommend over-the-counter treatments to try. If your acne is severe or over-the-counter treatments haven’t worked, see your GP.

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you, and will ask you about your medical history. Your GP will usually diagnose acne based on your symptoms because acne is easy to recognise by the pattern of spots on your body. There are different types of acne and the most common is acne vulgaris. Your doctor will be able to tell you which type you have and what the best treatment is.

If your acne is severe, your GP may refer you to a dermatologist (a doctor who specialises in treating conditions that affect the skin). It’s important to see a specialist as soon as possible if you have severe acne as treatment may help to prevent scars from developing.

Self-help for acne

There are a number of things you can do to help acne, which include the following.

- Try not to pick or squeeze your skin as this can make acne worse and lead to acne scars.

- If you smoke, try to quit. Smoking increases your chances of acne scars.

- Gently wash spot-prone areas with a gentle cleanser and warm water, or an oil-free soap substitute. Acne isn’t caused by poor hygiene, so extra washing or scrubbing doesn't make it better; it will just make acne worse. You don’t need to wash your skin more than twice a day.

- It’s better for your skin not to wear make-up. But if it makes you feel more confident to do so, choose products that are non-comedogenic as these shouldn’t cause blackheads, whiteheads, or acne. Remove all your make-up at night.

- If your skin is dry (some acne creams can cause dry skin), use a moisturiser made for acne-prone skin.

- If you need to shave your face, use a gentle facial cleanser rather than shaving products. Shave downwards, following the direction of the hair growth.

- Use cosmetics (moisturisers, shaving gels and cleansers) that are designed especially for acne. Ask a pharmacist for advice about these.

- Don’t let shampoo or any other hair products get on your face.

Over-the-counter medicines that you can buy from a pharmacy include the following.

- Benzoyl peroxide (for example, Brevoxyl). This is an antibacterial treatment that reduces the amount of P. acnes bacteria on your skin. Take care not to get any of your treatment on your clothes as products containing benzoyl peroxide may bleach the colour. Benzoyl peroxide may also bleach your hair. You might not see an improvement immediately and your skin might get a bit worse to start with but there are ways to manage this – just ask your pharmacist for advice.

- Salicylic acid. This acts as a chemical exfoliator. It works by getting into your hair follicles and oil glands and dissolving blocked dead skin cells, oil and other debris that can cause acne. It also helps to reduce the amount of oil produced by your oil glands, making it less likely that new acne-causing blockages will form or grow bigger.

- Niacinamide. This may help to reduce the swelling, redness and oil production that’s associated with acne. You can’t use this medicine if you’re pregnant.

This is just a selection of what’s available – ask your pharmacist for more information.

Mental health support

Having acne can be very distressing and can really affect your confidence. For example, it can affect your self-esteem if people comment on your acne. Acne can lead to anxiety and depression in some people.

If acne is making you feel low, it’s important to talk to someone you trust for support. You could talk to your GP for help and advice, or friends, family and support groups. You may also find it helpful to talk to a counsellor. You may be able to get in touch with a counsellor through school, university or work. It’s important to see a dermatologist too if your acne doesn’t respond to treatment and is affecting your mood and self-esteem.

Treatment of acne

The best acne treatment for you will depend on how severe your acne is. You may need to take a combination of medicines.

If you have tried to treat acne with over-the-counter medicines such as benzoyl peroxide but it hasn’t worked, your GP may prescribe one of the treatments below. Be patient with any treatment you take – it can take four to eight weeks to see an improvement and several months to see a big improvement. When you first start treatment, your skin might feel more irritated but this should get better. If this happens, you could try stopping the treatment for a few days and then build up slowly, but check with your doctor first.

Acne creams, lotions and gels

- Topical retinoids such as tretinoin. It may take several months before you notice the effects of these medicines. Your skin may become more sensitive to sunlight when you use a retinoid so make sure you use plenty of sunscreen if you go out in the sun.

- Azelaic acid. This is an antibacterial medicine usually used as an alternative to benzoyl peroxide and retinoids. It's less likely to irritate your skin as much. It’s also available over-the-counter in a lower concentration.

- Antibiotic lotions or gels, such as clindamycin or erythromycin. These can help to reduce inflammation (swelling) by reducing the levels of natural P. acnes bacteria on your skin. You’ll usually take antibiotic lotions or gels in combination with benzoyl peroxide.

Antibiotic tablets and capsules

If you have moderate or severe acne and acne creams and lotions haven’t worked, your GP may prescribe antibiotic tablets or capsules for acne, such as oxytetracycline, lymecycline or doxycycline.

Your GP will tell you how many times a day you need to take your medicine and for how long. Most people who try this treatment find their acne gets much better after three months, but antibiotics may continue to work for a number of months, or even longer. But you shouldn’t take these long term as it can be harmful. If you have tried antibiotics but they don’t help, you may need to try an alternative treatment, such as the contraceptive pill (see below). Your doctor may also give you a retinoid cream or lotion, or benzoyl peroxide to use at the same time.

Contraceptive pill

If you have hormonal acne, your GP may prescribe a contraceptive pill (that you swallow). This will suppress the hormone testosterone, which can increase sebum production. Another option to reduce testosterone may be a medicine called spironolactone.

If you have severe acne and antibiotics haven’t helped, your doctor may suggest you take a medicine called co-cyprindiol. This works as a type of contraception and reduces the levels of testosterone in your body. Your doctor will discuss the risks and benefits of this treatment with you.

Oral isotretinoin

If your acne is more severe, your doctor may advise you to take an oral retinoid medicine called isotretinoin (eg Roaccutane). This reduces the amount of sebum your skin produces. This is a strong medicine and is only prescribed by, or under the supervision of, a dermatologist.

Your acne may get worse for a few weeks when you start taking oral isotretinoin before it begins to improve.

Isotretinoin can cause side-effects, such as:

- dry eyes, lips and skin

- nose bleeds

- general pain in your body

- severe headaches

- effects on your night vision

It may also cause more serious problems, such as liver problems or raise your cholesterol levels. You’ll need to have regular blood tests to check for any problems, for example to check your cholesterol levels. Experts aren’t sure if isotretinoin can cause depression, but your doctor will monitor you for this. If you’ve had depression in the past, let your dermatologist know before you start treatment.

When you use isotretinoin, try and stay out of direct sunlight and use sunscreens and moisturisers (including lip balm).

Consider contraception too because isotretinoin could harm your baby if you’re pregnant. You’ll need to have a regular pregnancy test and a review meeting to discuss how your treatment is going. You can talk about these and other issues with your dermatologist and ask questions before you start treatment.

Light treatment

Treatments that involve therapy with light or lasers are being developed. Doctors aren't sure how well light therapy works for acne yet and research is still ongoing. Before these therapies are offered as treatments, more scientific proof is needed to show how useful they are. These treatments aren’t available on the NHS. You would need to have private treatment, which you will need to pay for. Ask your dermatologist for more information.

Complications of acne

Acne scars

Acne usually clears up as you get older without leaving any acne scars. But one in five people with acne do get scars. Usually, people with severe acne get scars, although milder acne can also leave them. If you pick and squeeze the spots, it can also cause acne scars.

Scars can be narrow ‘ice pick’ scars or broader deeper scars. Less often, ‘keloid’ (firm lumpy) scars develop on your skin.

Treatment for acne scars

Several treatments have been designed to reduce and improve acne scars but at the moment there isn’t much evidence that any of them work. Treatments include the following.

- Dermabrasion and chemical peels. A chemical peel uses chemicals to remove the damaged outer layers of your skin, after which your body produces a new layer of skin. Dermabrasion is where the top layers of your skin are removed using a hand-held mechanical instrument. This smooths the surface of your skin and over the next week or so new skin cells grow and the skin heals. Chemical peels and dermabrasion can tighten the skin and lift the scars to reduce the depth of them, to help make them less noticeable.

- Laser resurfacing. This uses lasers to produce the same effect as dermabrasion and chemical peels.

- Microneedling. This uses a tool to create several, tiny injuries within a scar. These usually heal within two days and form new collagen (a protein that helps give your skin strength and elasticity) inside the scar. As the new collagen forms, it reduces the scar’s depth.

These treatments don’t remove scars completely and the end results will vary. They aren’t available on the NHS because they’re considered to be cosmetic surgery. If you want to find out about treatments for acne scars, contact one of the many private clinics that offer these treatments. Make sure that you do your research and that any treatment you have is done by a qualified professional. See Other helpful websites for more information.

Other tips for scars

Skin creams can keep your scar moisturised so it doesn’t become dry. Scars can be particularly sensitive to sunlight. So it’s important to wear sunscreen to protect your skin when you go out in the sun.

There are make-up products, such as creams and powders designed to help cover up some types of acne scars. These match your skin colour but they can’t fill in scars or flatten out raised scars. You can access these products through a Skin Camouflage Service. You can refer yourself or your doctor may be able to refer you. To find out more about this service run by the charity Changing Faces, see Other helpful websites.

Dark and light spots

Acne can change your skin tone and this may be more noticeable if you have a dark skin tone. It usually isn’t permanent.

- Hyperpigmentation is when your skin becomes darker in the areas affected by acne.

- Hypopigmentation is when your skin becomes lighter in the areas affected by acne.

It’s important to use sun lotion on your skin to protect it from the sun. Skin camouflage is an option to help with changes in the pigmentation of your skin.

Acne is usually divided up by how severe it is, so there’s mild, moderate or severe acne. If you have very severe acne, cysts may join together on your skin to form larger, deeper inflamed areas. This is called acne conglobata.

See our section: Symptoms of acne above for more information.

There are a number of things you can do to help acne and avoid flare-ups. These range from using cosmetics that are designed especially for acne, to not picking or squeezing spots. These can make acne worse and lead to acne scars. Over-the-counter medicines may help to treat your symptoms. And your doctor can prescribe treatments if these don’t help.

See our sections: Self-help for acne and Treatment of acne above for more information.

Acne is very common in teenagers and young adults − about 9 in 10 people aged 12 to 24 have had acne at some point. It's less common in later life but adults can get acne too. And newborn babies can sometimes get acne in their first six months.

See our section: About acne above for more information.

Acne is caused by having too much of a natural oil in your skin called sebum and dead skin cells that block your hair follicles. Your skin can produce too much oil during your teenage years due to changes in your hormones. Certain things can increase your chance of developing acne, such as having polycystic ovary syndrome, and taking medicines such as corticosteroids. Acne can also run in families.

See our section: Causes of acne above for more information.

Stick with any treatments that your pharmacist or doctor recommends to avoid breakouts. Be patient as it can take four to eight weeks to see an improvement and several months to see a big improvement. When you first start treatment, your skin might feel more irritated. If this happens, your doctor may advise you to use it less often or stop use until the irritation settles down. You can then try again using a lower dose or use it less often.

See our sections: Self-help for acne and Treatment of acne above for more information.

Several treatments have been designed to reduce and improve acne scars. But there isn’t much evidence that any of them work. Treatments to get rid of acne scars include laser resurfacing, dermabrasion and chemical peels, and a procedure called skin needling. These treatments aren’t available on the NHS because they’re considered to be cosmetic surgery. Ask your dermatologist if any of these are an option for you.

See our section: Complications of acne above for more information.

Other helpful websites

- British Association of Dermatologists

- Changing Faces

- British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Acne information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Acne vulgaris. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised June 2021

- Yang Z, Zhang Y, Mosler EL, et al. Topical benzoyl peroxide for acne. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011154.pub2

- Acne. British Association of Dermatologists. www.bad.org.uk, updated July 2020

- Acne vulgaris. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 10 February 2022

- Acne vulgaris. Patient. patient.info/doctor, last edited 21 July 2021

- 10 skin care habits that can worsen acne. American Academy of Dermatology. www.aad.org, accessed 10 March 2022

- Menstruation and pregnancy. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Acne vulgaris. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 28 August 2020

- Acne. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 25 February 2022

- Guide to acne scarring. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, published 2018

- Shaving for acne-prone people. Acne.Org. www.acne.org, accessed 14 March 2022

- Benzoyl peroxide. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 25 February 2022

- Salicylic acid. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Niacinamide. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Isotretinoin. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 25 February 2022

- Azelaic acid. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Antibiotics. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Barbieri JS, Choi JK, Mitra N, et al. Frequency of treatment switching for spironolactone compared to oral tetracycline-class antibiotics for women with acne: a retrospective cohort study 2010-2016. JDD 2018; 17(6):632–38. jddonline.com

- Retinoids. British Association of Dermatologists. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Scars and keloids. British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. baaps.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Ice-pick scars. British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. www.acnesupport.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- What is the skin camouflage service? Changing Faces. www.changingfaces.org.uk, accessed 10 March 2022

- Chemical peels. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 26 July 2017

- Dermabrasion. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 18 May 2018