Coronary angioplasty

Your health expert: Professor Mark Westwood, Consultant Cardiologist

Content editor review by Victoria Goldman, Freelancer Health Editor, Bupa Health Content Team, June 2023

Next review due July 2026

Coronary angioplasty is a procedure to open up narrowed or blocked arteries in your heart. This makes your blood flow more easily, so your heart muscle can get the oxygen it needs. Coronary angioplasty may be used to treat angina symptoms or as an emergency treatment for a heart attack.

How coronary angioplasty is carried out

Animation | Coronary angioplasty procedure | Watch in 2:24 mins

Coronary angioplasty is a procedure used to unblock blood vessels that supply your heart with blood. Watch the animation to find out more about the procedure.

About coronary angioplasty

Your coronary arteries supply your heart with oxygen. In coronary heart disease, these arteries can become narrowed and blocked. If this happens, your heart muscle may not get enough oxygen, and this may lead to angina or a heart attack.

If you have a heart attack, your doctor may recommend you have a coronary angioplasty. This procedure unblocks your coronary artery so blood flows through it more easily. You may hear several different names for a coronary angioplasty. These include:

- percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

- balloon angioplasty

- percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA)

Our information here is a general guide – your individual care may differ. You’ll be given the information you need beforehand by your hospital. Before your procedure, you’ll meet the doctor who’ll carry it out to discuss what’s involved.

Alternatives to coronary angioplasty

Stable angina can usually be controlled with medicines and by making changes to your lifestyle, such as exercising or stopping smoking.

A coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) operation may be a better option for you if coronary angioplasty isn’t suitable.

Your doctor will be able to explain your options and discuss what’s best for you.

Preparing for a coronary angioplasty

Your cardiologist (a doctor who specialises in conditions that affect the heart) or hospital will give you information about how to prepare for your procedure.

If you smoke, you’ll be asked to stop. This is because smoking makes any treatment you have for heart disease less likely to work. If you’re taking any medicines, ask your doctor if you need to stop taking them before your angioplasty.

If you're having a planned coronary angioplasty procedure, you should be able to go home the same day. But some people will need to stay overnight in hospital. You’ll need someone to drive you home when you leave hospital. If possible, they should stay with you for 24 hours. Usually, you can’t eat or drink anything for a few hours before an angioplasty.

Angioplasty is usually done under local anaesthesia. You’ll be given an injection of local anaesthetic into either your wrist or groin, depending on how your doctor is going to do the procedure. You’ll be awake during the procedure but the anaesthetic will block any pain. You may also have a sedative, which will help you to relax. Your doctor will discuss with you what will happen before, during and after your procedure, and any pain you might have. This is your opportunity to ask questions so that you understand what will be happening. You don’t have to go ahead with the procedure if you decide you don’t want it. Once you understand the procedure and you agree to have it, your doctor will ask you to sign a consent form.

Coronary angioplasty procedure

You’ll probably have your angioplasty in a specially equipped room called a catheterisation laboratory (‘cath lab’, for short). Coronary angioplasty usually takes about an hour. But this depends on how many narrowed arteries need treatment.

Your doctor will give you medicines to stop your blood clotting (anticoagulants). These help to reduce the risk of a blood clot forming in your artery wall or stent.

After the local anaesthetic has started working, your doctor will make a small cut in your wrist or groin. Guided by X-ray, your doctor will put a thin flexible tube (a catheter) into the artery that leads to your heart. Once the catheter is in place, they’ll inject a dye called contrast medium. This shows up the blocked areas of your blood vessels on the X-ray. You may feel a warm sensation when the contrast medium goes in.

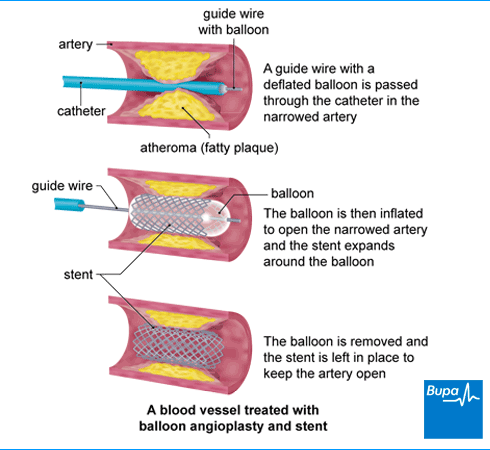

Your doctor will use the X-ray images to guide a wire down the catheter to the narrowed or blocked area in your coronary artery. Then they’ll insert a small balloon next to the blockage and gently inflate it. This makes your artery wider to allow blood to flow more easily. Once this is done, they’ll deflate and remove the balloon, along with the wire and the catheter. You may have a bit of chest pain when the balloon is inflated. Tell the doctor so they can give you some painkillers.

Your nurse will press firmly on your entry wound for about 10 minutes to make sure the artery in your wrist or groin closes and any bleeding stops. They may then use a device to seal the hole in your artery. If you had the procedure through your wrist, your doctor may put a tight band over the artery for a couple of hours.

Stents

Your doctor is very likely to put in a stent to keep your coronary artery open. A stent is a very small wire mesh tube. The stent is collapsed when it’s put into your artery. But it expands to fit against your artery walls when your doctor inflates the balloon. It then stays in place after the balloon is removed.

Your doctor is likely to use a stent coated with a medicine. This is called a drug-eluting stent. The medicine is released slowly into your artery to stop it closing up again.

Aftercare for a coronary angioplasty

You need to rest after a coronary angioplasty. Your nurse will monitor your blood pressure and pulse regularly and check your wound for bleeding.

If you had the procedure done through a cut in your groin, you’ll need to stay in bed lying on your back for a few hours. If the procedure was done through a cut on your wrist, you’ll be able to sit up soon after the procedure.

Someone will need to take you home and stay with you for the first 24 hours after your procedure, if they can.

If you’ve had a sedative, you may find you’re not as coordinated as usual or that it's difficult to think clearly. This should pass within 24 hours. In the meantime, don't drive, drink alcohol, operate machinery or sign anything important.

You may be given a date for a follow-up appointment, and details of who to contact if you have any problems.

Recovering from a coronary angioplasty

If you have any pain from the wound, you can take over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine. If you have any questions about taking medicines, ask your pharmacist.

When you get home, check your wound regularly. You may have some bruising. Contact your hospital if:

- you get any swelling

- the area feels hard or painful when you touch it

- the bruising starts spreading

If your wound starts to bleed, press on it firmly and contact your hospital straightaway. If it’s bleeding heavily, phone 999.

It usually takes about a week to recover fully from a planned coronary angioplasty but everyone recovers differently. Don’t lift anything heavy or do any strenuous activity for the first week or so. Follow your doctor's advice about what you can do during this time.

If you had an emergency angioplasty, it may take longer to recover – ask your doctor or nurse for advice. You’ll probably need to take medicines, such as aspirin and clopidogrel for up to a year or more after angioplasty. This is to help prevent your blood from clotting.

Working and driving

Depending on your job, you may be able to go back to work after a few days. But some people need to take more time off. This depends on the type of work you do and how well you’re recovering.

You don’t need to tell the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) that you’ve had a coronary angioplasty. But if you drive a car or motorcycle, you shouldn’t drive for:

- one week if your angioplasty was successful and you don’t need any more surgery

- four weeks if you had an angioplasty after a heart attack but it wasn’t successful

Before you go back to driving, check with your doctor. You should also contact your insurer to make sure your insurance remains valid.

If you drive a bus, coach or lorry, you must tell the DVLA you’ve had a coronary angioplasty. You won’t be able to drive these vehicles for at least six weeks. Then your doctor needs to check you’re well enough to return to work. The DVLA may also ask you to have some tests before you can go back to driving.

Keeping active

Regular exercise can help to keep your heart healthy. If you had a heart attack before your procedure, you’ll usually be invited to attend a cardiac rehabilitation programme soon after your coronary angioplasty. This will give you advice on how to exercise and get back to everyday life.

You’ll need to take things easy at first and gradually increase your activity levels. Walking is a great way to start getting exercise. After a few weeks, you may want to try a bike or going for a gentle jog.

If you become breathless or have any chest pain when you exercise, stop and rest and contact your GP or NHS 111. Or use your glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) spray or tablets if you’ve been prescribed them. If your symptoms don’t ease or get worse, phone 999.

An angioplasty should improve the flow of blood to your heart. So if you had angina symptoms before, these should get better. If all goes well with the procedure, you should be able to do more and your quality of life should improve.

Side-effects of a coronary angioplasty

During an angioplasty and for the first few hours afterwards, you may have some mild pain or discomfort in your chest. Tell your doctor or nurse if this happens.

You may have some pain or bruising where the catheter was put in. This is common and doesn’t need any special treatment.

If you have any redness, swelling or lots of bruising after you get home, contact the hospital.

Complications of a coronary angioplasty

Complications are problems that occur during or after a procedure. Coronary angioplasty is generally a safe procedure and the risk of complications is usually low. Possible complications of angioplasty are listed here.

- Bleeding from your wound causing a collection of blood (haematoma) to form – you may need a small operation to repair your artery.

- Narrowing of the treated coronary artery (re-stenosis), usually within six months of having the procedure – you may need another angioplasty.

- A blockage in the stent can happen during the procedure or at any time afterwards – this stops blood flowing to your heart muscle, so you have a heart attack. You will usually need an emergency coronary angioplasty to open up the artery again.

- An allergic reaction to the dye used during the procedure may cause a rash or breathlessness – your doctor will be checking for this.

- A stroke or heart attack – caused by a clot breaking away from the original blockage to block an artery further on.

Some of these complications are very rare. The chance of them happening is different for everyone. Ask your doctor to explain how these risks apply to you.

An angioplasty is a procedure that opens up narrowed or blocked coronary arteries. A stent is a small metal tube that’s often inserted during an angioplasty to keep your arteries open. For more information, see our about coronary angioplasty and coronary angioplasty procedure sections.

Exercising after an angioplasty will help to keep you healthy and reduce your chances of further heart problems. But you need to start slowly and build up gradually. For more information, see our recovering from coronary angioplasty section

There are lots of things you can do to reduce your risk of more heart problems. These include stopping smoking, eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and taking any medicines your doctor recommends. For more information, see our recovering from coronary angioplasty section.

Most people find their angina symptoms get better after an angioplasty. But it’s possible that the narrowing of your arteries comes back and grows into the stent. If this happens, your angina symptoms may come back. See our complications of coronary angioplasty section for more information.

An angioplasty doesn’t involve making any big cuts in your body. Most people recover fully within a week or so. It’s usually a safe procedure and the risk of serious complications is generally low. For more information, see our recovering from coronary angioplasty section.

High cholesterol

Cholesterol is a type of fat (lipid) made by your body and found in some foods.

Coronary heart disease

Angina

Angina is when you have chest pain or an uncomfortable tight feeling in your chest.

Other helpful websites

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Coronary angioplasty information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention. Patient. patient.info, last updated September 2016

- Coronary angioplasty. BMJ Best Practice Patient Information. bestpractice.bmj.com, last published June 2020

- Coronary artery atherosclerosis. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated April 2021

- Stable ischaemic heart disease. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed April 2023

- Acute myocardial infarction management. Patient. patient.info, last updated December 2020

- Angiography. British Society of Interventional Radiography. www.bsir.org, accessed May 2023

- Coronary angioplasty. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published May 2018

- Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) Technique. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated November 2019

- Good surgical practice. The Royal College of Surgeons. www.rcseng.ac.uk, published September 2014

- Angioplasty and stenting. British Society of Interventional Radiography. www.bsir.org, accessed May 2023

- Caring for someone recovering from a general anaesthetic or sedation. Royal College of Anaesthetists. rcoa.ac.uk, published November 2021

- Heart attacks, angioplasty and driving. DVLA. www.gov.uk, accessed May 2023

- Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. 19 Medical therapy, secondary prevention and strategies for follow up. Eur Heart J 2018; 40 (2):87–165 academic.oup.com, published January 2019

- Coronary angioplasty and stents. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed May 2023

- Epidemiology of coronary heart disease. Patient. Patient.info, last updated November 2022

- Personal communication, Professor Mark Westwood, Consultant Cardiologist, July 2023