Coronary heart disease

Your health expert: Dr Joshua Chai, Consultant Cardiologist

Content editor review by Liz Woolf, April 2023

Next review due April 2026

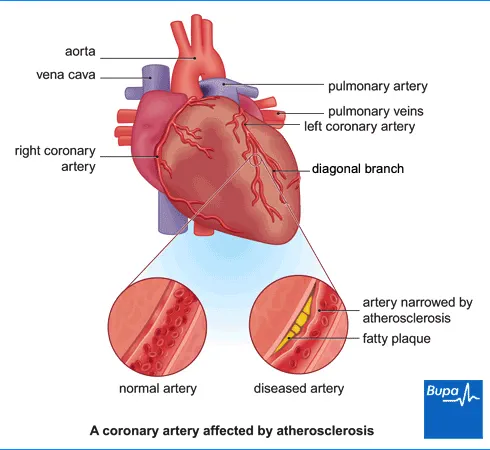

Coronary heart disease is when fats build up inside the arteries that carry blood to your heart. This can make your arteries narrower. Then your heart might not get enough oxygen, which may cause chest pain and affect your breathing. Coronary heart disease can also increase your risk of a heart attack in the future.

What is coronary heart disease?

Your heart pumps blood to your lungs and the rest of your body. The blood carries oxygen and nutrients to all your body cells. Your heart gets its own supply of blood from your coronary arteries.

Coronary heart disease is when fatty substances build up inside your coronary artery walls. These fatty build-ups are called plaques. Doctors call this process atherosclerosis. As a plaque forms, it narrows the space inside your artery, reducing blood flow. This means your heart muscle doesn’t get all the oxygen it needs.

If a plaque bursts, a clot can form on top of it. This may suddenly block your artery completely, causing a heart attack. Coronary heart disease may weaken your heart, which can lead to heart failure. This means your heart doesn’t pump blood around your body as well as it should.

You’re more likely to have coronary heart disease as you get older. It’s the most common cause of death in adults in the UK.

There are lots of things you can do to reduce your chance of getting coronary heart disease. And if you do develop it, treatment can help to control symptoms and protect against serious problems.

Causes of coronary heart disease

You’re more likely to have coronary heart disease if you:

- smoke

- are overweight – especially if you have excess fat around your waist

- aren’t very active

- have a South Asian background

- have diabetes

- have high blood pressure

- have high cholesterol

- have a family history of heart disease

- eat an unhealthy diet with a lot of foods that are high in saturated fat, cholesterol, salt and sugar

Symptoms of coronary heart disease

You might not have any symptoms of coronary heart disease. You may only realise there’s a problem with your arteries if you have a heart attack. But you may have chest pain (angina) and feel short of breath. You may also feel sick or as if you have indigestion.

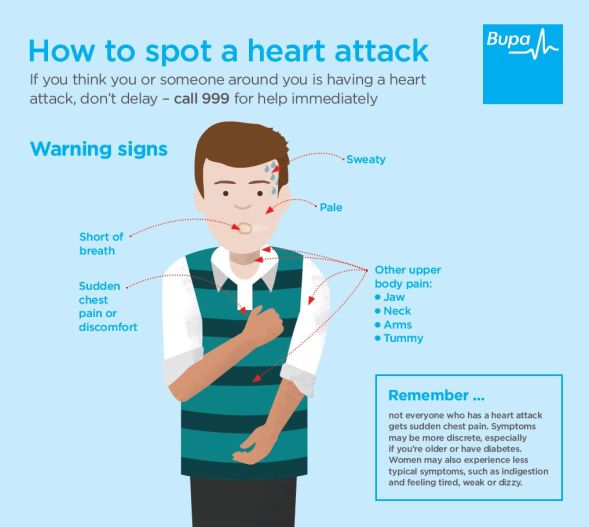

How to spot a heart attack

If you think you may be having symptoms of a heart attack, dial 999. Don’t delay.

See our infographic on how to spot a heart attack (PDF, 0.7MB) or click on the icon below.

These symptoms can be caused by lots of other things too, so it’s important to discuss them with your GP.

Diagnosis of coronary heart disease

If you are concerned about coronary heart disease, see your GP. Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. They may ask about your lifestyle – whether you smoke and how active you are.

If your GP thinks you may have a problem with your heart, they will refer you to a cardiologist. This is a doctor specialising in conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels.

You may need to have one or more of the following tests.

- Blood tests to check the levels of fat, cholesterol, sugar, and protein in your blood.

- An electrocardiogram (ECG) to check the electrical activity of your heart. An ECG can show up damage to your heart muscle or signs of coronary heart disease. An ECG may be normal, even if you have coronary heart disease.

- An exercise ECG (also called an exercise tolerance test or an exercise stress test) is an ECG while you’re on a treadmill. It can show if your heart gets the oxygen it needs when it’s working harder.

- An echocardiogram uses ultrasound to check the structure of your heart and to see how well it’s working.

- A CT scan (also called non-invasive coronary angiogram) checks your coronary arteries for fatty plaques or calcium, which can build up and cause blockages.

- A myocardial perfusion scan uses a small injection of radioactive tracer. A camera picks up the rays this sends out as it passes through your heart. It can show how well blood flows through your heart muscle. You may have this test while exercising and when resting.

- A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan uses magnets and radio waves to create images. It can give your doctor more information about the quality of the blood supply to your heart muscle.

- An invasive coronary angiogram is called invasive because you have a thin tube (catheter) put into your wrist or groin. You then have an injection of a harmless dye through the catheter and into your coronary arteries before having an X-ray. The dye helps to show blood flow and any blockages in your coronary arteries.

Self-help for coronary heart disease

If you have coronary heart disease, there’s a lot you can do to reduce your risk of further problems in the future. Your doctor may suggest making some changes to your lifestyle including:

- stopping smoking

- losing weight if you’re overweight

- keeping active and exercising regularly

- eating a healthy diet , with fewer saturated fats to reduce high cholesterol levels

- getting help if you’re feeling stressed or very down

- taking any medicines that your doctor recommends

- managing any other health conditions you have such as high blood pressure or diabetes

- getting a flu jab every year

Your GP may arrange for you to join a local cardiac rehabilitation programme. This usually involves:

- some exercise that’s right for you

- advice on lifestyle changes, such as dealing with stress and healthy eating

For more information, see our section on prevention of coronary heart disease.

Treatment of coronary heart disease

There are lots of treatments available for coronary heart disease. These can help to manage the condition and improve your health. They may ease your symptoms and lower your chances of more serious heart problems.

These treatments include:

- changes to your lifestyle (for more information, see our section on self-help)

- medicines

- surgery

You and your doctor will discuss your options and the best treatments for you.

Medicines

Your doctor may offer you one or more medicines to treat coronary heart disease. These medicines work in different ways.

- Antiplatelet medicines and anticoagulant medicines make your blood less likely to form clots. This reduces your risk of a heart attack.

- Statins reduce how much cholesterol your liver makes. It is cholesterol that forms the fatty plaques in your arteries in coronary heart disease. Statins also help to stop plaques bursting inside your arteries. If you can’t take statins, there are other cholesterol-lowering medicines.

- Beta-blockers slow your heart and reduce the amount of work your heart must do. They can also help to control your heart rhythm.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors lower your blood pressure to reduce strain on your heart. You may have these if you have heart failure or have had a heart attack.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers are another option if you have side-effects that stop you taking ACE inhibitors.

- Calcium-channel blockers relax and widen your arteries and can slow your heart rate.

- Nitrates relax your coronary arteries and allow more blood to reach your heart muscle. You may have a fast-acting tablet to put under your tongue if you get heart pain (angina).

Your doctor will discuss which medicines may work best for you and why. This may depend on your symptoms and what’s causing your condition. It may also depend on any other health problems you have. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine. If you have any questions, ask your pharmacist or doctor.

Our handy medicines checklist helps you see what to check for before taking a medicine. Bupa's medicines checklist PDF opens in a new window (0.8MB)

Hospital treatment

If medicines don’t control your symptoms, your doctor may recommend you have treatment to improve blood flow to your heart. You may have:

- a coronary angioplasty to widen a narrowed coronary artery

- a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) operation, to divert blood flow around narrowed or blocked coronary arteries

Your doctor will talk through the best options for your circumstances.

Prevention of coronary heart disease

Healthy lifestyle changes can reduce your risk of getting coronary heart disease. This means eating a healthy diet, being active and not smoking . To find out more about leading a healthy lifestyle to prevent coronary heart disease, see our section on self-help.

If your GP thinks you’re at a high risk of coronary heart disease, they may recommend regular medication.

Bupa Weight Management Plan

The Bupa weight management plan is designed for people with a BMI over 30 (or over 27 if you have a weight related condition). The plan is designed to empower you to achieve and maintain a healthy weight in a sustainable way.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 03452660566∧

Living with coronary heart disease

Being diagnosed with heart disease can be a shock. You will almost certainly need to make changes to your lifestyle. Our section on self-help has information about how you can improve your health – for example, by eating more healthily and taking more exercise.

You may be concerned about driving. The Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) has strict rules about when you can or can’t drive with a heart condition. You can continue to drive with angina unless it affects you when you are resting or under emotional stress. If you’ve had a heart attack , you can’t drive for a month afterwards. The DVLA has a leaflet about driving with a heart condition (PDF, 0.6MB) that you may find useful. If in any doubt at all, speak to your GP. You also need to tell your motor insurer about your diagnosis and treatment. If you don’t, you may not be insured.

Another issue that commonly comes up is sex. For most people, there’s no reason why you can’t continue to have a healthy sex life. After all, it’s a form of exercise. Some people have a lower sex drive or problems having sex that are due to anxiety or their medication. Speak to your doctor if you’re having problems or are at all worried.

There are many possible causes of heart disease. Some are related to an unhealthy lifestyle – smoking, being overweight, unhealthy diet or lack of exercise. Some people have a higher risk because of their ethnicity or family background.

There is more information in our section on the causes of coronary heart disease.

People don’t always have symptoms with heart disease. You may have chest pain, particularly when you’re exercising or emotionally stressed. You may also feel breathless or dizzy and sick.

For more information, see our section on symptoms of coronary heart disease.

No, coronary heart disease isn’t curable. Once you have fatty plaques in your arteries, you can’t get rid of them completely. But with lifestyle changes and medication you can stop it getting worse.33 If they follow their doctor’s advice, more than half of those diagnosed with angina can be symptom free a year after diagnosis.

There is more information in our sections on self-help and treatment for coronary heart disease.

If you’re concerned about heart disease, you can ask your GP for a cardiovascular risk assessment. They’ll use information about your medical and family history, lifestyle, and health checks. Such information includes your weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol level. Depending on your risk, your GP may suggest more tests or medication. They’ll also discuss changes to your lifestyle – for example, stopping smoking, losing weight, and taking more exercise.

For more information, see our section on self-help for coronary heart disease.

Angina

Angina is when you have chest pain or an uncomfortable tight feeling in your chest.

Heart attack

High blood pressure (hypertension)

Coronary angioplasty

A coronary angioplasty is a procedure to open up narrowed or blocked arteries that can be caused by coronary heart disease.

Did our Coronary heart disease information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Coronary artery atherosclerosis. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated April 2021

- Stable ischaemic heart disease. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last updated June 2023

- Overview of coronary artery disease. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, last reviewed June 2022

- Coronary heart disease. Medline Plus. medlineplus.gov, last reviewed February 2022

- Heart failure – chronic. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised June 2023

- Epidemiology of coronary heart disease. Patient. patient.info, last updated November 2022

- The health of people from ethnic minority groups in England. The Kings Fund. kingsfund.org.uk, last updated May 2023

- Coronary artery atherosclerosis clinical presentation. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated April 2021

- Stable angina. Patient. patient.info, last updated March 2022

- Atherosclerosis. Patient. patient.info, last updated November 2022

- Radionuclide imaging of the heart. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, last reviewed July 2021

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Sarase Antti, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020; 41(3):407–77

- Diabetes. British Heart Foundation. bhf.org.uk, last reviewed October 2021

- Cardiac rehabilitation. British Heart Foundation. bhf.org.uk, accessed July 2023

- Lipid-regulating drugs. Patient. patient.info, last updated June 2023

- Beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed July 2023

- Drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed July 2023

- Calcium-channel blockers. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed July 2023

- Nitrates. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed July 2023

- Car or motorcycle drivers with heart conditions. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. gov.uk, last updated May 2019

- Driving with a heart or circulatory condition. British Heart Foundation. bhf.org.uk, last reviewed November 2021

- Sex and heart conditions. British Heart Foundation. bhf.org.uk, last reviewed July 2023

- Treatments of coronary heart disease. British Heart Foundation. bhf.org.uk, accessed July 2023.

- What is coronary heart disease? Royal Bromptom and Harefield Hospitals Specialist Care. rbhh-specialistcare.co.uk, published April 2023

- Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). nice.org.uk, last updated May 2023