Osteoporosis

- Dr Sundeept Bhalara, Consultant Rheumatologist

Osteoporosis is a condition where your bones gradually become weaker and more fragile. This means they’re more likely to break (fracture). Osteoporosis is more likely in older age. But it can also be caused by a number of other medical conditions and treatments.

How osteoporosis develops

How our bones work | How osteoporosis develops | Watch in 2 minutes 50

This video explains what osteoporosis is and how it affects our bones.

About osteoporosis

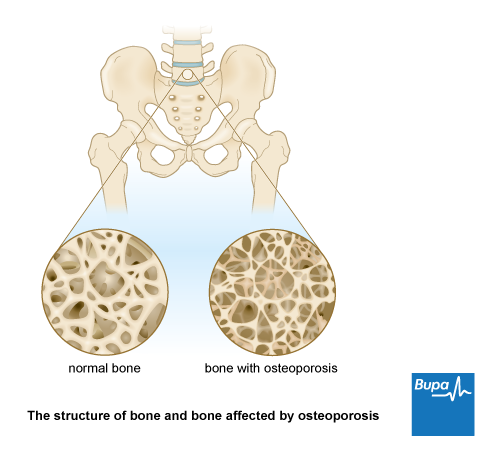

Healthy bones are made up of a strong mesh surrounded by a thick outer layer. This mesh is made of protein and minerals, particularly calcium. It is living tissue that’s constantly renewed by the cells in your bones. These cells usually work in balance, some of them building up bone, others breaking it down. Osteoporosis happens when your body breaks down bone faster than it builds it up.

Osteoporosis is more common in women but men can get it too. If you have osteoporosis, it doesn’t mean that you will definitely fracture a bone. But it does mean they’re more likely to.

Causes of osteoporosis

The main cause of osteoporosis is ageing. Your bones are at their most dense in your 30s. But from your 40s onwards, your bones gradually lose their density as a natural part of getting older.

For women, bone loss speeds up considerably in the first few years after the menopause before slowing down again. Other things that increase risk of osteoporosis include:

- ethnicity – white people are more likely to get osteoporosis

- family history, especially if your mother had osteoporosis or a broken hip

- spending a lot of time sitting, or being bedbound for a long time

- being underweight or having lost a lot of weight

- not getting enough calcium, vitamin D or other minerals in your diet

- smoking

- drinking too much alcohol

Some health conditions can increase your risk of osteoporosis. These include:

- an overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism) or overactive parathyroid glands (hyperparathyroidism)

- rheumatoid arthritis

- a low level of testosterone

- digestive disorders – for example, coeliac disease or lactose intolerance

- diabetes

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- chronic kidney or liver disease

Some medicines can increase your risk of osteoporosis. These include corticosteroids, epilepsy medicines and some cancer treatments. Ask your doctor to explain the risks and benefits of taking these medicines. Do not stop taking them without discussing with your doctor.

Symptoms of osteoporosis

Osteoporosis itself doesn’t cause symptoms. The first sign of osteoporosis may be if you break a bone in a fairly minor fall or accident.

Fractures are most likely to happen in your back (vertebrae), hip and wrist. They can also happen in your arm, pelvis, ribs and other bones.

A fractured wrist or hip is likely to be painful. But only one in three people with a fracture of the bones in their back have any symptoms. If you do get symptoms they may include:

- pain – this may be sudden or worse when you move

- height loss

Pain usually gets better within a few weeks, as the fracture heals. But pain can become long-term (chronic) if you have more than one fracture in your back. In time, you can also develop a curve in your spine. Eventually this can look like a hump that makes you stoop forwards.

Diagnosis of osteoporosis

Your doctor will assess you if you’re at risk of osteoporosis, or you break a bone and they suspect that’s the cause. They’ll ask questions about your lifestyle and family medical history. They’ll examine you and may arrange a bone density scan. This is called a DEXA (dual energy X-ray absorptiometry) scan which measures the density of your bones.

The scan shows if your bone density is normal, slightly low (this is called osteopenia) or more significantly lowered (osteoporosis). The lower your bone density, the more likely it is you may fracture a bone.

You may also have some blood tests to rule out other conditions.

Your doctor may put your scan results into an online risk assessment tool. They add your age, sex, if you smoke and whether other people in your family have osteoporosis. The tool produces a score, which helps your doctor estimate your risk of a fracture within the next 10 years.

Self-help for osteoporosis

Your GP will talk through any changes you need to make to your diet and lifestyle. And they might suggest some changes to your home to help reduce your risk of falls. For more information, see our sections on Prevention of osteoporosis and Living with osteoporosis.

Your GP may also recommend you take calcium and vitamin D supplements. Together these help to prevent fractures. It’s important to follow your doctor’s advice on which supplements to take and how many.

Treatment of osteoporosis

Osteoporosis treatment aims to lower your risk of fractures. Your doctor may prescribe a medicine to keep your bones as strong as possible.

The main medicines used to treat osteoporosis are below.

- Bisphosphonates (such as alendronate and risedronate) slow down bone loss.

- Denosumab stops your body making cells that break down bone.

- Raloxifene is an artificial hormone that copies the effects of oestrogen on your bones.

- Teriparatide stimulates your cells to make bone. It’s a form of the hormone that regulates calcium levels in your body (parathyroid hormone).

- Romosozumab speeds up the activity of bone-making cells and slows down the cells that break down bone.

You generally take bisphosphonates for five to 10 years. They can have side-effects when you take them long term. Your doctor will see you once a year to check that all’s well. They may also suggest pausing treatment from time to time, to reduce the risk of side-effects.

Depending on the most suitable treatment for your situation, your medicine may be prescribed by your GP or by a hospital specialist. Your doctor will talk this through with you. The most suitable treatment for you will depend on:

- your age

- your sex

- the risk that you’ll have a fracture

- if you’ve already had a fracture due to osteoporosis

- other medical conditions you may have

- whether any medicines you take for other conditions could affect your bones (steroids, for example)

Sometimes low testosterone levels cause osteoporosis in men. Your doctor may suggest testosterone replacement therapy.

Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine. If you have queries, ask your pharmacist.

Physiotherapy services

Our evidence-based physiotherapy services are designed to address a wide range of musculoskeletal conditions, promote recovery, and enhance overall quality of life. Our physiotherapists are specialised in treating orthopaedic, rheumatological, musculoskeletal conditions and sports-related injury by using tools including education and advice, pain management strategies, exercise therapy and manual therapy techniques.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0345 850 8399

Complications of osteoporosis

The main complication of osteoporosis is getting a fracture (break) in one of your bones. This is most commonly in your hip, ribs or wrist, but other fractures can happen too.

With osteoporosis, your bones can fracture much more easily than you’d expect. This could be after quite minor accidents like falls or trips, or even bending and lifting.

Fractures are often painful and may cause some difficulties with everyday living. For some people, fractures can cause long-term disability.

Prevention of osteoporosis

Changes to your lifestyle could help to reduce your risk of developing osteoporosis. A healthy diet and regular exercise can increase your bone mass when you're young. It can also slow down the rate of bone loss in later life.

Exercise

Weight-bearing exercise helps to build and maintain strength in your bones and muscles. This may improve your balance and reduce the likelihood of falls and fractures.

Try to be active every day. Aim to do at least two and a half hours of moderately intensive activity each week, such as brisk walking. Also do some muscle strengthening activities at least two days a week, for example, weight lifting, yoga or carrying shopping. If you aren’t used to exercise, start slowly and build up your routine gradually.

If you’d like to be more active, our walk-to-run programme (PDF, 0.2 MB) is a good place to start.

Smoking and alcohol

Smoking can harm your bone strength and can also cause an early menopause. Stopping smoking reduces your risk of future hip and spine fractures. There’s a lot of help available if you decide to give up smoking. Ask your pharmacist and GP practice how they can help. There are also online sources of help to stop smoking.

Drinking too much alcohol can lower your bone density and increase your risk of fracture. Drinking heavily can also increase your chance of falls and fracturing a bone. The recommended limits for low risk drinking are up to 14 units a week, or no more than 2 units a day on average.

Healthy diet

It’s important to eat a healthy balanced diet to keep your bones healthy. It’s particularly important to eat a diet that’s rich in calcium. For more information, see our section on Calcium and Osteoporosis.

Vitamin D

To absorb calcium properly, you need vitamin D. You can get vitamin D from foods, such as oily fish, eggs and some breakfast cereals. But your body also produces vitamin D when your skin is exposed to the sun. In the UK, it’s recommended to take a vitamin D supplement during the autumn and winter months. If you have osteoporosis, you should take vitamin D supplements daily, all year round.

Calcium and osteoporosis

Calcium in your diet is important to help prevent and treat osteoporosis.

The amount of calcium you need changes at different stages in life.

- Between 11 and 18, boys need a daily intake of 1,000mg calcium and girls need 800mg. Their bones are growing rapidly during this time.

- Most adults need around 700mg of calcium every day. You should be able to get this in a balanced diet.

- If you’re breastfeeding, you need 1,250mg.

If you’re having treatment for osteoporosis, you need 1,000mg of calcium a day. Your doctor may suggest taking a daily supplement of calcium and vitamin D.

The everyday foods listed below are all good sources of calcium.

- A 200ml glass of semi-skimmed milk – 240mg calcium.

- A 150g pot of fruit or plain yogurt – 240mg calcium.

- Cheddar cheese (matchbox size piece) – 240mg calcium.

- Two slices of white bread –120mg calcium.

- Two slices of wholemeal bread – 60mg calcium.

- Tinned salmon (half a tin) – 60mg calcium.

- Baked beans (small tin, 220g) 120mg calcium.

If you don’t drink milk or have dairy foods, it can be a little harder to get the calcium you need. Oher foods rich in calcium include soya beans, tofu, and green vegetables like kale and broccoli. Some foods have added calcium. Look for calcium-enriched milk alternatives, orange juice and breakfast cereals.

Living with osteoporosis

There’s a lot you can do to keep yourself healthy and reduce the chance that you’ll have a fracture. Some aspects of your life may need to change, but it’s important to keep active and continue to enjoy life. Below is some information on changes you may need to make. Some charities also offer helpful advice – for contact details, see our section: Other helpful websites.

Avoiding falls

You might worry about falling and breaking a bone, especially as you get older. But there are some practical, simple ways to help prevent falls. These include:

- making changes to your home

- wearing shoes that fit well

- improving your muscle strength, fitness and balance through exercise

Check your home for hazards – trailing wires, clutter and rugs that slip or are curling increase your risk of tripping up. Ask your GP if there’s a specialist NHS falls-prevention service in your area, which can give advice. You may also be able to get help with home aids or modifications from social services.

Being active

If you have osteoporosis, it’s important to stay active as it can reduce your risk of falls and fractures. You need a combination of weight bearing, strength and balance exercises. It’s important to start exercise slowly and build up over time. If you have any medical problems, check with your GP before you start any new exercise regime.

Fractures

Osteoporosis doesn’t affect the healing process. Fractures usually heal within six to 12 weeks, but may take longer. Your treatment and recovery will depend on the type of fracture you have.

Over-the-counter painkillers may help with pain from a fracture. Your pharmacist can help you find the right type of pain relief for you. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine. If you’re finding it hard to control your pain, contact your GP.

If you have a hip fracture, you may need extra help from healthcare specialists. For example, physiotherapists and occupational therapists can help you get your independence back.

Getting support

You may find it helpful to talk to other people who have osteoporosis. There may be a support group near you, or you could join an online forum. The Royal Osteoporosis Society has a directory of support groups. They also offer information and advice. For contact details, see our section: Other helpful websites.

The main cause of osteoporosis is getting older. Your bones are most dense in your 30s. But from your 40s onwards, your bones gradually lose their density as a natural part of ageing.

For more information, see our causes of osteoporosis section.

You can’t feel osteoporosis – it doesn’t have any symptoms. But if you have a fracture, it will probably be painful. A fracture in your spine may cause sudden pain that may be sharp, ‘nagging’ or dull. Unfortunately, in some people the pain can last after the fracture has healed.

For more information, see our symptoms of osteoporosis section.

Osteoporosis treatment aims to keep your bones as strong as possible and lower your risk of fractures. There are different medicines that help to do this. Your doctor will discuss with you which treatment is best for you.

For more information, see our treatment of osteoporosis section.

Your doctor may recommend you take supplements of calcium and vitamin D if you are taking a medicine to treat osteoporosis. Follow your GP’s advice on which supplements to take and how many.

For more information, see our treatment of osteoporosis section.

Fractures

A fracture is a broken or cracked bone.

Vitamins and minerals

Different vitamins and minerals do different things: some help your body to digest food while others build strong bones

Exercise for older people

Being active is an important part of a healthy lifestyle for everybody, particularly for staying healthy into old age

How to start exercising

We should all be getting active – and it may be easier than you think. Here we give you tips and advice for getting started

Did our Osteoporosis information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Osteoporosis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed September 2023

- Osteoporosis –prevention of fragility fractures. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised April 2023

- Osteoporosis. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated December 2022

- Living with osteoporosis. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Endocrinology and Diabetes. Oxford Medicine Online. academic.oup.com, published November 2021

- Osteoporosis symptoms. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Osteoporosis Clinical Presentation. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated December 2022

- Osteoporosis. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, last updated September 2023

- NOGG: Clinical guideline for the treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Guideline Group. nogg.org.uk, last updated September 2021

- Evaluation of Bone Health/Bone Density Testing. Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. bonehealthandosteoporosis.org, last reviewed March 2022

- Alendronic Acid. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Denosumab. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Raloxifene and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. nice.org.uk, last updated February 2018

- Osteoporosis. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Bending forward with osteoporosis. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Osteoporosis Treatment and Management. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, last updated December 2022

- UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines. UK Government Chief Medical Officers. assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, published September 2019

- Menopause. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised September 2022

- Godos J, Giampieri F, Chisani E, et al. Alcohol consumption, bone mineral density and risk of osteoporotic fractures: A dose-response meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(3):1515, DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19031515

- UK Chief Medical Officers' Low Risk Drinking Guidelines. Department of Health. assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, published August 2016

- Vitamin D for bones. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Calcium. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. ods.od.nih.gov, last updated October 2022

- Calcium. British Dietetic Association. bda.uk.com, last updated March 2021

- Osteoporosis and diet. British Dietetic Association. bda.uk.com, last updated July 2023

- Avoiding slips, trips and falls. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. nice.org.uk, published June 2013

- Apply for a needs assessment by social services. UK Government. gov.uk, accessed October 2023

- Gorter EA, Reinders CR, Krijnen P, et al. The effect of osteoporosis and its treatment on fracture healing a systematic review of animal and clinical studies. Bone Rep 2021; Dec 15:101117. DOI: 10.1016/j.bonr.2021.101117

- Recovering from a broken bone. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Pain relief medications. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, accessed October 2023

- Osteoporotic spinal compression fractures. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed September 2023

- Living with osteoporosis: pain relieving drugs after fracture. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, published November 2017

- Daily living after fractures. Royal Osteoporosis Society. theros.org.uk, last reviewed April 2023

- Liz Woolf, Freelance Health Editor