Pulmonary embolism

- Dr Edward Cetti, Consultant Respiratory Physician

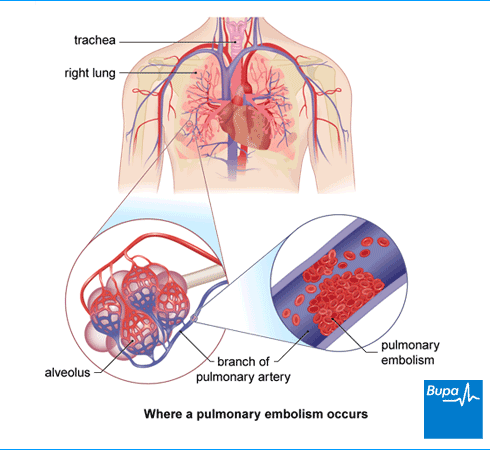

A pulmonary embolism happens when a blood clot blocks one or more blood vessels in your lungs. It’s a serious and potentially life-threatening condition if you don’t get a quick diagnosis and treatment.

Causes of pulmonary embolism

The most common cause of a pulmonary embolism is deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This is a blood clot in a vein in your leg or your pelvis. Parts of this clot can break off and travel through your bloodstream. The clots can get stuck in the narrow blood vessels in your lungs. This can affect your blood flow and breathing.

Doctors can’t always find out what’s caused a pulmonary embolism. But some things can increase your risk of developing a blood clot. These include:

- being inactive for long periods of time – for example, after a big operation or sitting still during a long journey of at least four hours

- having blood that clots more easily – this is more likely in people who are overweight, pregnant or taking the contraceptive pill or some forms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- having cancer, including pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer and breast cancer

- after a recent accident or broken bone

- your blood vessels being damaged from an injury or operation

- having a genetic disorder that makes it more likely for your blood to clot

Symptoms of pulmonary embolism

The symptoms of a pulmonary embolism can be vague and persistent for several weeks. Or they can be sudden and severe. Some people have few, if any, symptoms.

Symptoms of a pulmonary embolism may include:

- pain in your chest – especially when taking a deep breath

- feeling short of breath

- coughing up blood

- feeling faint or fainting

Your symptoms may depend on how big the pulmonary embolism is and where it is.

- If the clot is small and in a blood vessel at the outer edge of your lungs, you may have mild symptoms.

- If the blood clot is large and in a central blood vessel, it could cause you to collapse suddenly.

If you have pulmonary embolism symptoms, including difficulty breathing and chest pain, call an ambulance and get medical help as soon as you can. Also get emergency help if you’re pregnant, or have given birth in the last six weeks.

Pulmonary embolism-type symptoms can be caused by other health conditions such as asthma. But if you have any of the above symptoms, it’s important to see a GP as soon as possible.

Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism

If the GP thinks you have signs of a pulmonary embolism, they’ll probably give you some medicines to take straight away. They’ll also arrange for you to go to hospital for assessment as soon as possible. You may already be in hospital (after an operation, for example) when the symptoms start.

At hospital, you may have the following tests.

- A blood test called D-dimer. If the test result is negative, this may help to rule out deep-vein thrombosis and a pulmonary embolism.

- A leg vein ultrasound. This uses sound waves to look at your blood as it flows through the blood vessels in your legs.

- Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA). This is a CT scan – dye is injected into your bloodstream to see if there’s a blockage in the arteries (blood vessels) to your lungs.

- Isotope lung scanning (also called ventilation-perfusion or V/Q scanning). You may be offered this test if you have kidney problems or can’t have a CTPA for some other reason. It shows how much blood and air are getting into your lungs.

Your doctor may do other tests such as a chest X-ray, an ECG and blood tests, to check whether you have a pulmonary embolism or another condition.

Treatment of pulmonary embolism

If you have a pulmonary embolism, it’s important that it’s treated quickly. This means you’ll usually begin pulmonary embolism treatment while you’re waiting for tests or test results. You may need to be admitted to hospital if you’re not already in hospital. You may be given oxygen to help you breathe, and fluid through a drip if necessary.

The main pulmonary embolism treatment is a type of medicine called an anticoagulant. You may also need treatment to get rid of the existing clot.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants prevent blood clots forming or stop blood clots from getting bigger. Which type of anticoagulant your doctor recommends will depend on a number of things. These include:

- how serious your pulmonary embolism is

- your general health

- local guidelines

- availability of treatment

You take most anticoagulants to treat pulmonary embolism as tablets or capsules. But some anticoagulant medicines are given as an injection.

There are two main types of oral anticoagulant medicine:

- direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) – for example, apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban

- warfarin

DOACs may be the first option your doctor recommends. With these medicines, you don’t need to be monitored as closely as with older anticoagulants such as warfarin.

Some people with certain medical conditions or taking some medicines can’t take apixaban or rivaroxaban. If you can’t take these DOACs, your doctor may recommend you have an injection of an anticoagulant called heparin for at least five days. Then you’ll be offered dabigatran or edoxaban tablets or capsules.

If you’re taking warfarin, you’ll need to have a regular blood test to make sure the medicine is having the correct blood-thinning effect. This is called an international normalised ratio (INR) test. You won’t need to be monitored in this way if you’re taking a DOAC.

After a pulmonary embolism, you’ll need to keep taking anticoagulants for at least three months. Depending on your medical history and why you developed a pulmonary embolism, your doctor may recommend you continue taking anticoagulants for longer. This is to prevent more blood clots from developing.

If you’re taking an anticoagulant, your nurse or doctor should give you an anticoagulant information booklet. The booklet includes advice about how to take anticoagulants and any possible side-effects. You’ll also be given an alert card, which you should always carry with you.

Treatments to remove clots

If your doctor thinks you have a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, you may need treatment to remove it. You may be given a type of medicine called a thrombolytic. This helps to dissolve the blood clots.

If you’re seriously unwell with life-threatening blood clots or other treatments haven’t worked, your doctor may suggest an operation to remove the blood clot. This is called an embolectomy. There are several different ways in which this can be done.

- In an embolectomy using a catheter, the surgeon puts a thin tube inside your vein and moves it to where the clot is. They can then break up the clot via the catheter and remove it.

- In open surgery, your surgeon makes a cut in the blood vessel to take out the clot.

Prevention of pulmonary embolism

Preventing pulmonary embolism in hospital

If you’re in hospital for a major operation or because of illness, you may be more likely to develop a deep vein thrombosis or a pulmonary embolism. When you’re in hospital, your nurse or doctor will measure your risk of developing a blood clot. They may ask you to do the following.

- Drink plenty of fluids. If you can’t drink, you may be given fluids through a drip.

- Get up and start moving about as soon as you can after an operation or illness.

- Wear compression stockings to help your circulation.

- Use an intermittent pneumatic compression device. This is an inflatable cuff wrapped around your leg or foot. An electrical pump inflates it, squeezing your deep veins.

- Take anticoagulant medicines, such as heparin.

Reducing risks of pulmonary embolism when travelling

Your risk of developing a blood clot increases on journeys of longer than four hours. But there are some simple steps you can take to reduce your risk.

- Get up and walk around whenever you can.

- Wear loose-fitting clothing.

- Do leg exercises in your seat; such as bending and straightening your knees, feet, and toes every half hour.

- Choose an aisle seat if you can.

- Drink enough water (at least 250ml every 2 hours) so you don’t become dehydrated.

- Don’t drink a lot of alcohol.

You should speak to your GP if:

- you’ve recently had surgery

- you’ve had a blood clot before

- you have other health problems that make developing a clot more likely

They may suggest you wear compression stockings or flight socks while travelling. If you develop a painful and swollen leg or any breathing problems after a long journey, get medical advice as soon as you can. Be aware that it can take hours, days, or even weeks before you notice any pulmonary embolism symptoms.

Pulmonary embolism and pregnancy

You’re four or five times more likely to develop a blood clot (DVT and pulmonary embolism) if you’re pregnant (although it’s rare to get one). You also have a greater chance of having a pulmonary embolism just after you’ve had your baby, especially if you had a caesarean section.

Some anticoagulants may harm a developing baby, so you shouldn’t take these when you’re pregnant. These include warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban. If you’re taking warfarin or other anticoagulant tablets, and think that you might be pregnant, tell your doctor immediately.

If your doctor thinks you’re at high risk of getting a blood clot, they may offer you heparin injections while you’re pregnant. Heparin injections are safe to take when you’re pregnant because the heparin doesn’t pass from you to your baby. You may need to take anticoagulant medicines for at least six weeks after you have your baby.

Lower leg exercises to prevent DVT [Animation]

If you’ve already had a DVT, there are lifestyle changes you can make to reduce your risk of getting another one. These include stopping smoking, maintaining a healthy weight and regularly exercising. It’s also important to keep taking any medications you’re prescribed.

This video today is about deep vein thrombosis prevention, also known as DVT.

What DVT is, is the blood clots which can be caused by reduced circulation. In the video today, we're going to go through some desk-based exercises that you can do to help reduce the risk of having a DVT.

The first exercise is a heel raise, which you can do in sitting or in standing.

In sitting, you're just going to lift up onto the balls of your feet and then slowly go back down. As you lift up onto the balls of your feet you want to feel the calf muscles are engaging. Try and do this for about 30 seconds and repeat three times a day.

The next exercise is high knees. In a standing position, just start to lift one leg up, place it back down. Stay on the same side, moving the opposite arm forward as well, to help you balance.

To make this one harder and to work your calf muscles a bit more on this, you can raise onto your toe as you lift your knee up. Challenges your balance quite a lot with this one.

See if you can do three lots of ten of this exercise, as controlled as you can.

The next exercise is a leg extension. This is done in a sitting position still, and you just need a bit of space in front of you for this. You just start to point your toes and lift up and then flex on the way down. This also gets your calf muscles working if you move your ankle.

To make this one harder, you can do both legs at the same time. This is also working your quad muscles at the front of your legs as well, and if you're sitting up without using the back of your chair you're also working your core.

Again, to make it slightly harder, just raising your knees a bit as you do this as well will increase the amount of work through your core and through your legs.

Try and do three sets of ten.

The next exercise is the sitting hamstring and calf stretch. In the sitting position, you're just going to lengthen one leg straight ahead of you, pull your toes up to the ceiling on the straight leg. On the bent knee, place your hands and try and keep a tall position as you hinge forward as far as you can until you feel a stretch down the back of your legs.

If you need more of a stretch, bend forward into the stretch more.

Try and do this three times for 30 seconds.

The next exercise is sit to stand. This is a great one for getting your whole legs moving and circulation throughout all of your lower body.

Arms across your chest and just standing fully up and then sitting down. To make this harder, you can do it without a chair so you're just doing a squat.

If your pulmonary embolism is diagnosed and treated straightaway, you may make a full recovery. But some people have long-term breathing problems afterwards. And it can take several months to get back to your previous fitness levels. You may need to keep taking oral anticoagulants to reduce your chances of having another blood clot. For some people, this means taking the medicine for life.

Early signs of pulmonary embolism include chest pain, feeling short of breath, coughing up blood, and feeling faint. These symptoms may start suddenly or build up over several days or weeks. It’s important to seek medical help as soon as you notice the symptoms.

For more information, see our section on symptoms of pulmonary embolism.

Pulmonary embolism is most often caused by a blood clot in your leg or your pelvis. The blood clot is called a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Parts of this clot can break off and travel through your bloodstream to your lungs.

For more information, see our section on causes of pulmonary embolism.

Pulmonary embolism is caused by a blood clot. Some people have a family history of blood clots. But several other things can increase your risk. These include major surgery, being pregnant, being inactive for long periods of time or having some types of cancer.

For more information, see our section on causes of pulmonary embolism.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Other helpful websites

Did our Pulmonary embolism information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Pulmonary embolism. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed September 2024

- Pulmonary embolism. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised September 2023

- Pulmonary embolism. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated July 2024

- Venous thromboembolic diseases: Diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, last updated August 2023

- Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: Reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, last updated August 2023

- How is a pulmonary embolism diagnosed? Asthma + Lung UK. www.asthmaandlung.org.uk, last reviewed April 2021

- Anticoagulation – oral. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised April 2024

- Venous thromboembolism. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated October 2024

- Dabigatran etexilate. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated October 2024

- Heparin (unfractionated). NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated October 2024

- Apixaban. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated October 2024

- Pulmonary embolism. Patient. patient.info, last updated August 2024

- What can I do to avoid getting a pulmonary embolism? Asthma + Lung UK. www.asthmaandlung.org.uk, last reviewed April 2021

- Wang Y, Huang D, Wang M, et al. Can intermittent pneumatic compression reduce the incidence of venous thrombosis in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2020 Jan–Dec; 26:1076029620913942. doi: 10.1177/1076029620913942

- DVT prevention for travellers. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised November 2023

- Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Patient. patient.info, last updated June 2023

- Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Patient. patient.info, last updated April 2023

- Warfarin sodium. Pregnancy. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated October 2024

- Personal communication by Dr Edward Cetti, Consultant Respiratory Physician, January 2025

- Victoria Goldman, Freelance Health Editor