Cervical cancer

- Ms Shanti Raju-Kankipati, Gynaecologist

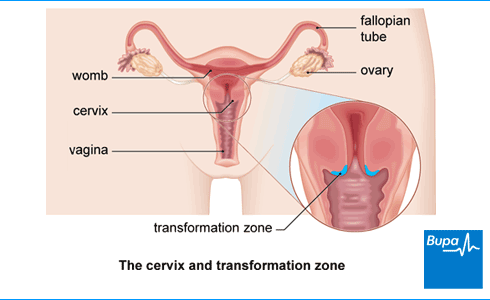

Cervical cancer is cancer that develops in your cervix, which is the neck of your womb. The cells in your cervix become abnormal and grow out of control. A virus called human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause of cervical cancer.

How cancer develops

Cancer explained | Watch in 1:48 minutes

In this video, we explain how, when cells divide uncontrollably, this leads to cancer.

About cervical cancer

Around 3,300 people are diagnosed with cervical cancer every year in the UK.

Cervical cancer is more common when you’re younger – most cases are in women aged between 30 and 34.

Cervical screening is also known as a smear test or a pap smear. It can discover human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and any changes in the cells of your cervix before they develop into cancer. If abnormal cells are caught early, cervical cancer can often be prevented. The NHS cervical screening programme saves thousands of lives every year.

Types of cervical cancer

There are two main types of cervical cancer. They’re named after the type of cell that becomes cancerous.

- Squamous cell cancer. About 8 out of 10 cervical cancers are squamous cell cancer. Squamous cells are flat skin cells that cover your cervix (the neck of your womb).

- Adenocarcinoma. Around 2 in 10 cervical cancers are adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinoma is a cancer that starts in glandular cells found in the passageway between your cervix and your womb.

You can also have a mix of the two types.

Other types of cancer of the cervix include adenosquamous carcinoma, small cell cancer, and lymphoma. These are very rare.

Causes of cervical cancer

Human papillomavirus

Almost all cervical cancers are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). There are many different types of HPV. Those that increase the risk of cancer are known as high-risk HPV.

HPV is a common virus that most people will get at some stage in their life. You can get it through having sex or sexual contact.

HPV doesn’t usually cause any symptoms and your immune system can fight it off, so you may never know you were infected. But for some people, the virus can stay in their body and cause the abnormal cells that can lead to cervical cancer. This may happen many years after the original infection.

In the UK, there’s a national vaccination programme against HPV for boys and girls aged 12 and 13. This programme aims to reduce the number of cervical and other cancers caused by HPV.

There’s also a HPV vaccination programme for men who have sex with men up to 45 years of age. Ask your GP if you have any questions about whether or not you’re eligible for this.

Other risk factors

Not all high-risk HPV infections lead to cancer. This means there must be other cervical cancer causes. If you’re infected with HPV, other things that might increase your risk of cervical cancer include:

- smoking

- having a weakened immune system – for example, because of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or immunosuppressant medicines

- having lots of babies, and starting young (under 17)

- having other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as chlamydia and herpes

- taking the oral contraceptive pill for longer than five years

- a family history (if your mother or sibling had it)

Symptoms of cervical cancer

You might not have any cervical cancer symptoms in the early stages. This is why it’s important to have regular cervical screening. Cervical screening is offered to all people with a cervix and aged between 25 and 64. If you’re registered as male with your GP, you won’t be invited automatically. Ask your GP or a local sexual health or family planning clinic to arrange cervical screening for you.

If abnormal cells develop into cervical cancer, you might develop cervical cancer symptoms. These may include:

- abnormal vaginal bleeding – for example, bleeding between periods, after you have sex or after you’ve been through themenopause

- a vaginal discharge which may smell unpleasant and have blood in it

- pain when you have sex

- pain in your pelvis

These symptoms aren't always caused by cervical cancer. But if you have them, go and see your GP.

What should I do if I'm embarrassed to talk to my doctor?

Seeing a doctor when you're embarrassed | Watch in 2:08 minutes

Dr Naveen Puri talks about how to make it easier to see a doctor about a health issue when you are feeling embarrassed.

Hello, I am Dr Naveen Puri, I am one of the GPs within Bupa Health Clinics.

Today I want to speak to you about embarrassing problems you might have and what we can do if you attend one of our clinics.

I want you to know that many people feel embarrassed or concerned about speaking about certain things with their doctors, but I'm here to reassure you these are the kinds of things we deal with every day.

For me, looking at someone's bottom or their breasts or their genitalia is no different to looking at their nose or elbow.

And that's true for all doctors as we train for many years in these parts of the body and are very used to having these conversations with people just like you.

So what I would encourage you to do if you have any concerns from your perspective, be it a change in your bowel habit, be it a lump, a rash, a swelling. Something on your genitalia or a part of your body you're not particularly familiar with or feel uncomfortable discussing.

Please be assured your doctor has done it all before.

Some of the ways we find patients find it easier to speak to a doctor is to either tell the doctor you feel embarrassed up front. That way a doctor can make extra effort to make sure you feel comfortable.

Or some patients come to us with pieces of paper and will write the problem down and hand it to us. That way we can help with whatever is going on for you as well.

You may also find it helpful to ask for a specific doctor, someone you're familiar with in your practice. Or you might want to ask for a doctor of a specific gender, or background to your liking as well.

I'd also say, doctors do this every day so don't be alarmed if we ask you certain questions around your symptoms. It is purely so we can help you get the best outcome for your enquiry.

And then finally, feel free to use language that suits you as well. We don't expect you to know the medical words for things, or a name for your diagnosis. That's our job to find out for you.

So, take your time, see a doctor, and hopefully we can help put your mind at ease.

Diagnosis of cervical cancer

Screening

The earliest signs that cervical cancer may be developing are usually picked up by cervical screening (a smear test). If this shows a human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, your cell sample will be tested for abnormal cells on your cervix (the neck of your womb). If you don’t have HPV, your cervical cells don’t need to be tested because HPV is by far the main cause of cervical cancer.

- If you have HPV but no cell changes, your GP practice will offer you another smear test (usually in a year’s time) to check that the infection has gone.

- If you have abnormal cells or have symptoms of cervical cancer, your GP will refer you to a gynaecologist. This is a doctor who specialises in women’s reproductive health.

Colposcopy

If you have abnormal cells or symptoms of cervical cancer, you’ll be given an appointment at a colposcopy clinic. A colposcopy is a test that uses a magnifying instrument called a colposcope to examine your cervix. A doctor or nurse who is trained in colposcopy will do the test.

Your doctor or nurse will look at your cervix and may take a small sample of tissue (a biopsy). The sample will be sent to a laboratory to be tested to see if the cells are abnormal and if so, how abnormal they are. Sometimes, your doctor might remove all of the abnormal cells straight away.

If you’re pregnant, it’s safe for you to have a colposcopy. If your doctor finds any abnormal pre-cancerous cells, treatment can normally wait until after you have your baby.

Treatment for abnormal cells

To remove the abnormal cells, your doctor will usually use a loop of wire with an electrical current passing through it, although there are other ways. This is called large-loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or loop diathermy. Your doctor or nurse will send the cells they remove to a laboratory to be tested.

If tests show that you have cervical cancer, your doctor may ask you to have a scan. This might be a CT (computed tomography) scan, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or a PET (positron emission tomography) scan. This is to see how far the cancer has grown into the tissues around your cervix and if it has spread further.

How healthy are you?

With our health assessments you get an action plan that’s tailor-made for you.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0345 600 3458

Treatment of cervical cancer

Your cervical cancer treatment will depend on the stage of cervical cancer and your general health. The stage of a cancer means how far it has grown and if it has spread to nearby lymph nodes or elsewhere in your body.

The main treatments for cervical cancer are either surgery or a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (chemoradiotherapy). Your treatment may affect your fertility. Ask your specialist doctor about this if you think you may want to have children in the future. They’ll explain the different treatments in more detail, what they involve and discuss which is best for you.

Surgery

The standard operation for cervical cancer is a hysterectomy, which involves removing your womb and cervix. The top of your vagina and some of the lymph nodes in your pelvis will be removed too. Lymph nodes (or glands) are part of your body’s natural defence system – the lymphatic system.

If you have early-stage cancer and you want to have children, it might be possible to have a procedure that will preserve your fertility. One option is a radical trachelectomy. In this operation, your surgeon will remove most of your cervix but leave enough behind so that you can still have a baby. They’ll also remove the lymph nodes in your pelvis.

Chemoradiotherapy

The main non-surgical treatment for cervical cancer is chemoradiotherapy, also called chemoradiation. This is where you have both chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Chemotherapy is a treatment to destroy cancer cells with medicines. Radiotherapy uses radiation – a beam of radiation is targeted on the cancerous cells to shrink the tumour.

You may have chemoradiotherapy as your only treatment or you might have it after surgery.

Treatment for advanced cervical cancer

If your cancer has spread into only one part of your body, you may have radiotherapy with chemotherapy.

If your cervical cancer is what’s called stage 4b, it has spread to another part of your body. Your doctor may call this secondary or metastatic cancer. There are treatments available. While they’re unlikely to remove your cancer completely, they may be able to control it for some time and improve your quality of life. Your doctor may suggest a combination of chemotherapy and a type of biological therapy that slows down the growth of cancer cells.

Having treatment

Your cancer team will give you advice on what cervical cancer treatment is possible and most likely to help you. All these treatments have different side-effects. Some are more difficult to get through than others. Talk to your cancer specialist about the side-effects of cervical cancer treatment, and make sure you know how the side-effects might affect you.

For most treatments, you can have the treatment as an outpatient (where you visit the hospital for your treatment but go home afterwards). But you’ll need to go into hospital as an inpatient (where you stay overnight) for some treatments.

Prevention of cervical cancer

There are things you can do to help prevent cervical cancer.

- Have regular cervical screening (smear tests) to pick up and treat any pre-cancerous cells in your cervix (neck of the womb). Screening can also detect cancerous cells at an early stage, when it can be better treated. Ask your GP if you would like to have a smear test but aren’t on the screening list.

- Have the HPV vaccine – this is now offered to all young people between 12 and 13 in the UK. It’s best to still go for your screening appointments even if you’ve had the HPV vaccine because the vaccine doesn’t protect against all types of HPV . Use condoms. These offer some protection against HPV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Help and support

An important part of cancer treatment is support to help deal with the emotional aspects as well as the physical symptoms. Specialist cancer doctors and nurses are experts in providing the support you need and they may visit you at home. If you have more advanced cancer, further support is available in hospices, hospital or at home. This is called palliative care.

For links to further support and information, see our section on other helpful websites.

Cancer awareness: cervical cancer

Cervical cancer awareness| Screening | Watch in 1:20 minutes

This animation explains the importance of attending cervical cancer screening so that if you have cervical cancer it can be detected early.

Cervical screening

Other helpful websites

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Cervical cancer information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- What is cervical cancer? Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 27 January 2020

- Cervical screening: helping you decide. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, updated 31 October 2021

- Gynaecology. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2020

- Cervical cancer and HPV. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised July 2021

- Cervical cancer. Patient. patient.info, last edited 27 September 2021

- Information on HPV vaccination. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, updated 9 November 2021

- How people get HPV. Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust. www.jostrust.org.uk, last updated 17 January 2020

- Guidance. Cervical screening: Programme overview. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, last updated 17 March 2021

- Guidance. HPV vaccination guidance for healthcare practitioners (version 5). UK Health Security Agency. www.gov.uk, updated 17 March 2022

- NHS population screening: Information for trans and non-binary people. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, updated 20 October 2021

- Minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 27 January 2021

- Cervical cancer. Symptoms. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 28 January 2020

- Cervical screening. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised December 2021

- Cervical screening: having a colposcopy. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, updated 31 October 2021

- Cervical cancer. Colposcopy. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 10 March 2020

- Cervical cancer. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 18 February 2022

- Cervical cancer. Tests to stage. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 18 March 2020

- Cervical cancer. Treatment for cervical cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 21 April 2020

- Cervical cancer. Treatment options. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 18 March 2020

- The lymphatic system and cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 20 July 2022

- Cervical cancer. About chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 30 March 2020

- Stages of cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 7 July 2020

- Cervical cancer. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 4 March 2021

- Palliative care – general issues. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised March 2021

- Cervical cancer. Risks and causes. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 26 May 2020

- Cervical cancer. Your sex life and cervical cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 20 May 2020

- Guidance. HPV vaccination: Guidance for healthcare practitioners. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, last updated 17 March 2022

- Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor