Ovarian cancer

Your health expert: Mr Joseph Yazbek, Consultant Gynaecologist and Gynaecological Oncology Surgeon

Content editor review by Victoria Goldman, October 2022

Next review due December 2026

Ovarian cancer is when cells in or around your ovaries start to grow abnormally and out of control. It’s most common in women over 50, but younger women can get it too.

About ovarian cancer

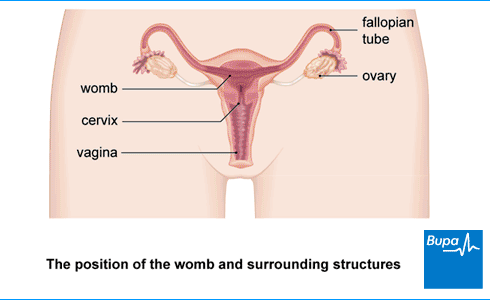

Your ovaries are two small, oval organs in your pelvis. Your pelvis is the lower part of your tummy, between your hip bones. Your ovaries release an egg every month. This is usually in the middle of your menstrual cycle.

Ovarian cancer starts inside your ovary or fallopian tubes (the tubes leading from your ovaries to your womb). It happens when the cells stop growing normally and start growing out of control.

Sometimes, ovarian cancer can spread out of your ovary and fallopian tube. It may spread more widely in your tummy. More rarely, it can spread to other organs, such as your liver, lymph nodes and lungs.

Ovarian cancer is the sixth most common cancer in women in the UK. Over 7,000 women are diagnosed with this type of cancer every year.

Types of ovarian cancer

There are several types of ovarian cancer. These start in different parts of your ovaries and are treated in different ways.

- Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common type. It causes 9 out of 10 ovarian cancers. It starts in the cells covering your ovaries and the ends of your fallopian tubes. There are different subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. These are named according to which type of cell is involved.

- Non-epithelial ovarian cancer is much less common. Again, there are different subtypes. The most common subtype grows from germ cells (the cells in your ovary that make eggs). This usually affects women under 35.

Borderline ovarian tumours tend to affect women aged 20 to 40. These are a special type of epithelial tumour. They tend to grow more slowly than cancer cells. They’re usually removed with surgery.

Your doctor will tell you which type of ovarian cancer you have, and how this will affect your treatment options.

How cancer develops

Cancer explained | Watch in 1:48 minutes

In this video, we explain how, when cells divide uncontrollably, this leads to cancer.

Causes of ovarian cancer

It’s not clear exactly why some women get ovarian cancer and others don’t. But certain things can make you more likely to get it. These include:

- having a family history of ovarian or breast cancer, or some other cancers, especially if you inherit faulty genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2

- getting older – most women who get it are over 50

- taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – this seems to increase your risk by a small amount

- being overweight or obese

- having endometriosis – increases your risk of some types of ovarian cancer by a small amount

- smoking

- starting your periods early

- starting the menopause late in life

Some things may make you less likely to get ovarian cancer. These include:

- taking the contraceptive pill

- having had children – the more children you’ve had, the lower your risk

- breastfeeding your children

- having had a hysterectomy or been sterilised (had your tubes tied)

Symptoms of ovarian cancer

The most common ovarian cancer symptoms include:

- pain or discomfort in your tummy or pelvis

- having a swollen tummy

- constantly feeling bloated

- feeling full quickly and losing your appetite

- needing to pee more often or more urgently

- unexplained changes in your bowel habits, such as constipation, excess wind or diarrhoea

- other symptoms affecting your digestive system, such as feeling sick or indigestion

Other symptoms include:

- losing weight for no obvious reason

- unexplained extreme tiredness

- abnormal bleeding from your vagina (such as after you’ve gone through the menopause)

- feeling short of breath

Many ovarian cancer symptoms are very vague and nonspecific. These may be similar to symptoms caused by other, less serious conditions. And many women don’t have symptoms at all in the early stages of the disease. This means that by the time many women see their doctor, their cancer is already at quite an advanced stage.

If you do have any of the symptoms listed above, you’re getting them regularly and they last for longer than a few weeks, contact your GP.

Diagnosis of ovarian cancer

Your GP will ask you about your symptoms and medical history. They’ll examine you by feeling around your tummy and pelvis. They may ask to examine you internally too. They’ll do this by gently feeling inside your vagina. They’ll check your womb and ovaries for any lumps or swellings.

Tests for ovarian cancer

Your GP may arrange for you to have a blood test. This may depend on your symptoms and how long you’ve had them. The blood test checks for a protein called CA125. A high CA125 level can be a sign of ovarian cancer. But other conditions can raise your CA125 level too. If your level of CA125 is found to be higher than normal, your GP may arrange for you to have an ultrasound scan to check your tummy and pelvis.

Referral to a specialist

Depending on your test results, your GP may refer you to a gynaecologist (a doctor who specialises in women’s reproductive health). Sometimes, your GP may refer you to a gynaecologist urgently (within two weeks), before doing any more tests. They’ll then organise any tests and scans for you.

Staging tests

Your doctor will look at your blood test results and ultrasound to see how large your cancer is and how far it’s spread. Sometimes you’ll need other tests too, such as a CT scan or MRI scan. Your doctor may recommend a procedure to remove a sample (biopsy) of your ovary to test for cancer cells instead.

Finding out how far your cancer has spread is called staging. Staging can help doctors to estimate how your cancer is likely to progress. It can also help them to decide on the best way to treat your cancer.

If your cancer is more advanced, your doctor will need to take tissue samples from the tumour. They may look at these with the CT scan to see the stage. The tissue samples are usually taken when the tumour is removed during surgery – see the section on treatment of ovarian cancer.

Genetic testing

You should be offered genetic testing after you’re diagnosed with ovarian cancer. This will check for faulty BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Having these faulty genes can increase your risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

If you haven’t been offered testing, talk to your doctor about whether you’re eligible. Knowing whether you have the faulty BRCA genes may help your doctor to plan your treatment better. There are lots of things to think about before having a genetic test – your doctor will talk you through what’s involved.

Looking for cancer cover that supports you every step of the way?

If you develop new conditions in the future, you can rest assured that our health insurance comes with full cancer cover as standard.

To get a quote or to make an enquiry, call us on 0800 600 500∧

Treatment of ovarian cancer

A team of specialist doctors, including a gynaecological oncologist (a surgeon who specialises in cancers affecting the female reproductive system), will be involved in planning your care. Which ovarian cancer treatment they recommend will depend on:

- the type of ovarian cancer you have

- whether it’s spread

- if it’s spread, how far it’s spread

They’ll talk to you about all the possible options. And they’ll discuss anything that may affect your decision, such as:

- your general health

- whether you plan to have children

Surgery

Almost all women with ovarian cancer have surgery. The aim of surgery is to remove as much of the tumour as possible. This is called cytoreductive surgery. It usually involves removing:

- both of your ovaries

- your fallopian tubes

- your womb (a total hysterectomy)

Your gynaecological oncologist may also remove some surrounding tissue (biopsies) and nearby lymph nodes. This will help them to find out how far the cancer has spread.

You may be able to just have the affected ovary and fallopian tube removed if your cancer hasn’t spread outside your ovary, and you want to have children in future.

Chemotherapy

Most women with ovarian cancer also have chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is a treatment for cancer that uses medicines to destroy cancer cells. It usually involves having several doses of chemotherapy medicines at regular intervals over a few weeks.

Most of the time, your doctor will offer you chemotherapy after surgery. This will destroy any cancer cells that weren’t removed by the operation. You may also be offered chemotherapy before surgery to shrink your tumour and make it easier to remove.

The exact chemotherapy treatment you’re offered will depend on the type and stage of your cancer. Your doctor will give you information on the type and course that’s best for you.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses radiation to destroy cancer cells. It’s not often used to treat ovarian cancer. But your doctor may offer it if your cancer comes back in another area of your body. Radiotherapy can also help to ease symptoms such as pain, if you can no longer have other treatments.

Targeted therapies

Newer medicines for ovarian cancer include:

- monoclonal antibodies

- PARP (Poly ADP-ribose polymerase) inhibitors

These medicines target cancer cells to stop them growing and multiplying. These may have fewer side-effects than traditional chemotherapy. You may be offered this treatment if:

- you’ve been found to have a faulty BRCA gene

- your cancer is advanced

- your cancer has come back

After your treatment

You’ll have regular check-ups after your treatment has finished. These will check how well your treatment has worked and see if the cancer has come back. It’s important not to miss these appointments, even if you’re feeling well. If your cancer has returned, your doctor will talk to you about any more treatment options you may be able to try.

Prevention of ovarian cancer

You may be able to reduce your chances of getting ovarian cancer by:

- stopping smoking

- losing excess weight

- being physically active

Taking these steps may help to reduce your risk of some other cancers too. They are also important for your general health. But making changes to your lifestyle can’t completely prevent ovarian cancer. There are many things that you can’t control, such as your age and your genes.

If you have a strong family history, your GP may refer you to a genetic counselling clinic. This is usually if you have two or more close relatives who have had breast or ovarian cancer. Specialists at the clinic will be able to assess your risk. They may advise you to get tested for the BRCA1 and BRCA2 faulty genes.

If you test positive for these genes, your doctor will talk to you about ways to reduce your risk of both breast and ovarian cancer. For ovarian cancer, you may be advised to:

- take oral contraceptives

- have regular ultrasound scans of your ovaries

- have surgery to remove your ovaries and fallopian tubes (risk-reducing surgery), depending on your age

Help and support

If you’ve been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, this can be distressing for you and your family. So it’s important that you have some support, especially while you’re having treatment. This will help you deal with the:

- emotional side of having cancer

- practical issues

- physical symptoms

Specialist cancer doctors and nurses are experts in providing the support you need – make sure you talk to them if you’re worried about anything.

Talking to your family and friends can help them to understand what you’re going through and how you’re feeling. Organisations and support groups that specialise in ovarian cancer (see the other helpful websites section) can also be a great source of information and support. You may also find it helpful to speak to someone else who has had ovarian cancer and been through treatment.

Chemotherapy

Hysterectomy

Gynaecological laparoscopy

In a gynaecological laparoscopy, your surgeon uses a camera (laparoscope) to see inside your lower abdomen (tummy). This means they will be able to see your womb (uterus), fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Did our Ovarian cancer information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Ovarian cancer. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised July 2018

- Ovarian cancer. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk, accessed August 2022

- Ovary anatomy. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated September 2018

- Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneal Cancer. The MSD Manuals. www.msdmanuals.com, last full review/revision July 2022

- Ovarian cancer incidence statistics. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed October 2021

- Ovarian Cancer. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed July 2022

- Ovarian cancer. Patient. patient.info, last edited October 2020

- Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline NG12. www.nice.org.uk, last updated December 2021

- Hereditary ovarian cancer. Target Ovarian Cancer. targetovariancancer.org.uk, last reviewed February 2020

- Principles of cancer therapy. The MSD Manuals. www.msdmanuals.com, last full review/revision September 2020

- Niraparib for maintenance treatment of relapsed, platinum-sensitive ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer. Technology appraisal guidance TA784. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) www.nice.org.uk, Published April 2022

- Cancer. World Health Organization. www.who.int, February 2022

- Coping with ovarian cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed January 2022

- Xia YY, Kotsopoulos J. Beyond the pill: contraception and the prevention of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2022 ;20(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13053-022-00227-z. PMID: 35668475; PMCID: PMC9169328

- du Bois A, Trillsch F, Mahner S, et al. Management of borderline ovarian tumors. Ann Oncol 2016;27 Suppl 1:i20-i22. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw090. PMID: 27141065

- Personal communication by Mr Joseph Yazbek, Consultant Gynaecologist and Gynaecological Oncology Surgeon, January 2023