Gynaecological laparoscopy

- Dr Joseph Yazbek, Consultant Gynaecologist and Gynaecological Oncology Surgeon

A gynaecological laparoscopy is a keyhole procedure to look inside your pelvis (lower tummy or abdomen) to examine your womb (uterus), fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Gynaecological laparoscopy can help to diagnose conditions (diagnostic laparoscopy) and to treat them where possible.

About gynaecological laparoscopy

A laparoscopy is keyhole surgery. This means a surgeon will make small cuts (incisions) in your tummy to do the procedure. It can be a safer alternative to open surgery, which involves a larger cut to open up your tummy. Laparoscopy usually has fewer complications and a shorter recovery time than open surgery.

Before you have a gynaecological laparoscopy, you may have other tests such as an ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computer tomography (CT) scan. You may have a gynae laparoscopy to investigate the reason for symptoms such as pain in your pelvis or to treat a condition.

The reasons for a gynaecological laparoscopy include:

- diagnosing and treating endometriosis

- removing scar tissue (adhesions)

- treating an ectopic pregnancy

- performing a sterilisation by sealing or blocking your fallopian tubes so that you can no longer get pregnant

- diagnosing and removing an ovarian cyst

- removing your womb (hysterectomy) or ovaries (oophorectomy)

- treating fibroids

- investigating long-term pain in your pelvis

- looking for reasons why you might not be getting pregnant if you’re having fertility problems

- investigating if you have cancer, if a cancer has spread, and to treat certain gynaecological cancers

Your doctor will explain why they recommend you have a gynaecological laparoscopy, and will talk about the benefits and potential risks involved. They’ll discuss with you what will happen before, during, and after your procedure, including any pain you might have. If you’re unsure about anything, don’t be afraid to ask. They’ll ask you to sign a consent form before the procedure, so it’s important that you feel fully informed.

Preparation for a gynaecological laparoscopy

A specialist doctor called a gynaecologist will usually carry out your gynaecological laparoscopy. Your hospital will give you information explaining how to prepare for your procedure.

You may have the procedure and go home the same day but sometimes you may need to stay in hospital overnight, so be prepared for this. Your doctor will let you know if this may be necessary. If you go home the same day, you’ll need someone to drive you and stay with you overnight.

A gynaecological laparoscopy is usually done under general anaesthesia, which means you’ll be asleep during the procedure. A general anaesthetic can make you sick, so you’ll need to stop eating and drinking for some time before your procedure. Check any fasting instructions with your hospital.

At the hospital, a nurse will test your pee (urine) to check that you’re not pregnant or have any conditions that could cause complications.

You may need to wear compression stockings to help prevent blood clots forming in the veins in your legs (deep vein thrombosis, DVT ). You may need an injection of an anticlotting medicine, as well as compression stockings for procedures that are likely to take longer.

Gynaecological laparoscopy procedure

Gynaecological laparoscopy usually takes about half an hour to two hours depending on what you’re having it for.

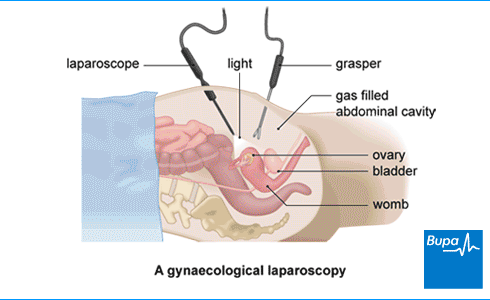

Your doctor will first make a small cut in your tummy, usually in or near your tummy button (navel). They’ll then put a needle through this cut and pass in carbon dioxide to gently inflate your tummy. This will allow your doctor to see better and give them room to move their instruments around.

Next, your doctor will insert a laparoscope through the same cut, to see inside your tummy. A laparoscope is a small tube with a camera and a light on the end. The camera on the laparoscope will send video images of the inside of your tummy to a monitor where your doctor can see it. Your doctor may then make one or more additional small cuts in your tummy to pass through any instruments needed for your procedure.

At the end of the procedure, your doctor will release the carbon dioxide gas from your tummy. They’ll close the cuts in your skin with stitches or glue.

Aftercare for gynaecological laparoscopy

You’ll need to rest until the effects of the anaesthetic have passed. You might have some discomfort as the anaesthetic wears off but you'll be offered pain relief.

If you had a laparoscopy for diagnosis, you’ll usually be able to go home after a few hours – as soon as you feel ready. Ask someone to take you home, and to stay with you for the first 24 hours while the anaesthetic wears off. If you had treatment as part of your laparoscopy, your medical team may sometimes ask you to stay in hospital overnight. Before you go home, your nurse will give you advice about caring for your wounds. You may be given a date for a follow-up appointment.

A general anaesthetic can affect how you feel for the next 24 hours. You might find that you're not so coordinated or that it's difficult to think clearly. In the meantime, don't drive, drink alcohol, operate machinery or make any important decisions.

Your stitches may dissolve on their own. If you have non-dissolvable stitches, you’ll need to have them taken out, usually after about five to seven days. A practice nurse at your GP surgery should be able to do this for you.

Recovery after gynaecological laparoscopy

The gynaecological laparoscopy recovery time can vary depending on the type of gynaecological laparoscopy procedure you have. Most patients feel comfortable to move around and go out within about a week.

If you had a diagnostic laparoscopy or small cyst removal, you can usually return to work after a week or two. But if you had more extensive surgery such as a hysterectomy, you’ll need to take around four weeks off work, especially if you have a physically demanding job. For all procedures, it can take time for your body to completely heal, so don’t lift anything heavy for a month.

You might have some pain and discomfort for a few days after your procedure. Your hospital may give you painkillers to take home. Or you can take over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. You may have some spotting or bleeding from your vagina, like a period, for a few days. Use sanitary pads until the bleeding stops.

Try to move around as much as you can after your laparoscopy because it will help to prevent blood clots forming in your legs. Even when you’re resting, move your feet and legs around. Your doctor may suggest you wear compression stockings or have blood-thinning injections for a while after your operation. These help to prevent blood clots too.

Don’t drive for at least 24 hours after your general anaesthetic. Only drive once you’re able to manoeuvre your car safely and comfortably, without any discomfort or pain. Check with your own insurance company to ask if they have their own conditions.

You can have sex as soon as you feel ready.

Side-effects of gynaecological laparoscopy

Side-effects are the unwanted but mostly temporary effects that you may get after having a gynaecological laparoscopy. Possible side-effects of a gynaecological laparoscopy include:

- a small amount of bleeding from your vagina

- pain and discomfort in your tummy

- pain in your shoulder (this is thought to be caused by the gas used to inflate your tummy irritating a nerve)

- feeling more tired than usual

- bruises around your wounds

Complications of gynaecological laparoscopy

Complications are when problems occur during or after your procedure. Complications of laparoscopy in gynaecology include the following.

- Infection of a wound. This may cause sore, red skin around your scars.

- Urine infection. You may have a burning or stinging feeling when you pee or you may need to pee more often.

- Hernia (bulging of tissue) near your wound. This causes a bulge under your skin. It can happen when a wound hasn't healed properly.

- Damage to organs in your tummy – for example, your bowel, bladder, womb or major blood vessels. Worsening pain in your tummy can be a sign of such damage.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – a blood clot in a vein in your lower leg. This may cause your leg to become red, swollen, and painful.

Seek medical help if you think you may have any of these complications.

The risk of serious complications is low for most people having a gynaecological laparoscopy. But some things can increase your risk. These include:

- being obese

- being older

- have had surgery on your tummy before

- have a long-term health condition

Your doctor will explain how these may affect you, and any special measures they can take to reduce your risk.

If you develop a complication during your laparoscopy, your doctor may need to convert from a keyhole procedure to open surgery. This means they’ll make a bigger cut in your tummy so they can identify the problem and treat it.

It’s also important to understand that the laparoscopy may not always identify a clear reason for any symptoms you have, such as pelvic pain.

Worried about your Period health?

A personalised care plan for heavy, painful or irregular periods for those 18 and over. Now available.

Gynaecological laparoscopy surgery is a keyhole procedure to diagnose and treat conditions that include endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, and fibroids. Gynaecological laparoscopy can be a safer alternative to open surgery, which involves a larger cut to open up your tummy. Laparoscopy usually has fewer complications and a shorter recovery time than open surgery.

For more information, see our section: About gynaecological laparoscopy.

Recovery time after gynaecological laparoscopy depends on the type of procedure you had. You can start getting back to your usual activities within three days after most gynaecologic laparoscopic procedures. But it will take longer to recover if you’ve had a hysterectomy, often two to three weeks.

For more information, see our section on recovery following gynaecological laparoscopy.

It depends on the type of procedure you have. If you’re having a laparoscopy to investigate symptoms, it can be a relatively minor procedure. But if you’re having more complex surgery, like a hysterectomy, it can be a major procedure. Your doctor will explain what to expect from the procedure and your recovery.

A gynaecological laparoscopy can help to diagnose several conditions. These include endometriosis, ovarian cysts, fertility problems, and cancer. Sometimes, a laparoscopy may not show any reasons for your symptoms. Your doctor may then suggest further tests or treatment.

For more information, see our section: About gynaecological laparoscopy .

Hysterectomy

Hysteroscopy

Did our Gynaecological laparoscopy information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Gynecologic laparoscopy. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 17 March 2023

- Sterilisation. Patient. patient.info, last updated 29 December 2022

- Laparoscopy – recovering well. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk, last updated 21 December 2023

- Laparoscopy. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 18 May 2023

- Diagnostic laparoscopy. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk, published June 2017

- Levy L, Tsaltas J. Recent advances in benign gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Fac Rev 2021; 10:60. doi: 10.12703/r/10-60.

- Morcellation for abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy or hysterectomy. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk, updated June 2023

- Laparoscopy. Encyclopaedia Britannica. www.britannica.com, last updated 21 September 2024

- Laparoscopy. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, reviewed/revised March 2023

- Caring for someone who has had a general anaesthetic or sedation. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published 2018

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy – recovering well. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk, last updated 21 December 2023

- Laparoscopy and laparoscopic surgery. Patient. patient.info, last updated 7 August 2023

- Wound infection. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 16 March 2023

- Deep vein thrombosis. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised June 2023

- Simko S, Wright KN. The future of diagnostic laparoscopy – cons. Reprod Fertil 2022. 3(2):R91–R95. doi: 10.1530/RAF-22-0007

- Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor