Gastroscopy

Your health expert: Dr Alistair McNair, Consultant Gastroenterologist

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor, July 2023

Next review due July 2026

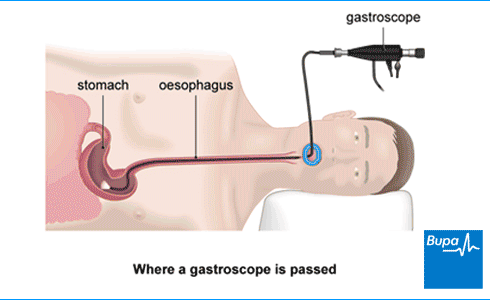

A gastroscopy is a test to look inside the tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach (oesophagus), your stomach and the first part of your small bowel (duodenum). You may have a gastroscopy to help find what’s causing certain symptoms. You can also have some types of treatment during a gastroscopy.

How a gastroscopy is carried out

How a gastroscopy is carried out | Watch in 2:14 minutes

A gastroscopy is a procedure that looks inside your oesophagus, stomach and the first part of the small bowel. Our animation shows the areas that can be viewed during the gastroscopy.

This animation shows how a gastroscopy is carried out.

A gastroscopy is a test that allows your doctor to look inside your food-pipe (oesophagus), stomach and the first part of the small bowel (duodenum).

Here in the animation, we show the areas of the digestive system which can be viewed using a gastroscope.

You may be given a sedative to help ensure that you are relaxed and comfortable during the procedure.

Your doctor may spray a local anaesthetic into the back of your throat or give you a lozenge to suck to numb your throat.

Your doctor will place a mouth guard over your teeth to protect them.

An endoscope is a narrow, flexible, tube-like telescopic camera. It's passed through your mouth.

You will be asked to swallow to help the endoscope pass into the oesophagus and down towards the stomach.

You should still be able to breathe normally during the procedure sometimes a little oxygen is given.

A nurse will help the doctor by using a suction tube to remove excess saliva from your mouth.

Air is usually pumped through the tube and into the stomach to make it expand and the stomach lining easier to see.

When this happens you may briefly feel a sensation of fullness or nausea.

A camera lens at the end of the endoscope sends pictures to a video screen.

Your doctor will look at these images to examine the lining of your oesophagus, stomach and duodenum.

Sometimes a biopsy is taken.

Special instruments are passed inside the endoscope and the doctor takes a sample of cells.

When the examination is finished, the endoscope will be taken out quickly and easily.

This is the end of the animation.

About gastroscopy

A gastroscopy is a type of endoscopy. This means the procedure is done using a narrow, flexible tube called an endoscope. This has a light at the end and a camera to allow a doctor or specialist nurse to see images of the inside of your body on a screen. Your doctor or nurse may take small samples of tissue (a biopsy) during the gastroscopy.

Other names for a gastroscopy are ‘upper gastrointestinal endoscopy’ and ‘oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD)’.

Preparing for a gastroscopy

A gastroscopy procedure is usually done as a day-case in hospital. This means that you’ll be an outpatient and you won't need to stay overnight. Before your gastroscopy, your hospital will give you information about what’s involved and how to prepare for your gastroscopy. It’s important to follow this advice – if you don’t, it may not be possible to have the procedure.

Before coming to hospital

The information from your hospital will tell you if you need to stop taking any regular medicines you have.

Let the hospital team know if you’re taking medicines to thin your blood. These include aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin. Your doctor will tell you if you need to stop taking them for a while. If you continue to take them, you may still be able to have a gastroscopy. But you probably won’t be able to have a biopsy or a treatment procedure.

If you would like to have sedation for the procedure (see below), you should arrange for someone to take you home after a gastroscopy and, if possible, stay with you overnight.

On the day

Your stomach must be empty during your gastroscopy procedure. This means you shouldn’t eat for six hours before. You may be able to have sips of water up to two hours before. It’s important to follow your hospital’s advice.

Tell your hospital team about any medicines you’re taking. This includes prescribed medicines and those you buy over the counter.

Your doctor or nurse will talk to you about what will happen before, during and after your procedure. They’ll ask if you want to have a local anaesthetic or sedation or both. The local anaesthetic is a spray that numbs your throat. The sedative will make you drowsy and more relaxed. If you have a sedative, you have it as an injection at the start of the procedure.

Ask your doctor or nurse to explain the pros and cons of having sedation or local anaesthesia. For instance, you may be more comfortable with a sedative. But if you choose this, you’ll need to have someone to take you home and keep an eye on you afterwards. If you choose to have the local anaesthetic spray, it may feel a little more uncomfortable at the time. But you won’t be drowsy afterwards.

You’ll have the chance to ask questions so that you understand what will happen. Once you understand the procedure and if you agree to have it, your hospital team will ask you to sign a consent form.

Gastroscopy procedure

A gastroscopy procedure usually takes only five to 10 minutes, though it might take longer. You should expect to be in the hospital for a few hours. Your gastroscopy will be done by a doctor or a specialist nurse.

They may ask you to take off your top and put on a hospital gown. If you have any false teeth or you wear glasses, you’ll need to remove them. You can leave contact lenses in.

If you’re having a local anaesthetic, your doctor or specialist nurse will spray the back of your throat. If you're having a sedative, they’ll give this through a fine tube into a vein in your arm. And they’ll attach a sensor to your finger to check your heart rate and oxygen levels during the procedure.

Your doctor or nurse will ask you to lie on your left side. They’ll place a guard into your mouth to protect your teeth, and then pass the gastroscope through it into your mouth. They’ll ask you to swallow to let the gastroscope pass into your oesophagus and down towards your stomach. This may be uncomfortable for a few seconds, and it’s usual to gag once or twice. The discomfort will usually pass quickly.

As the gastroscope passes down, your doctor or specialist nurse will watch images on a nearby screen. They’ll be able to see your oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. They will pass some air down the gastroscope to inflate your stomach, so they can see better.

If needed, your doctor or specialist nurse can pass special forceps down the gastroscope to take a biopsy (a small sample of tissue). They’ll send the samples to a laboratory to be tested.

You can have some treatments through the gastroscope. For more information, see our Uses of gastroscopy section below.

Uses of gastroscopy

Your doctor may recommend you have a gastroscopy to find out why you’re having certain symptoms. These include:

- indigestion that doesn’t go away with treatment or that returns when you stop treatment; you may have acid reflux or discomfort in your upper tummy

- difficulty when you swallow (food sticking in your oesophagus) or pain when you swallow

- pain in your chest or upper tummy

- being sick (vomiting) repeatedly

- vomiting blood or having very dark tar-like blood in your poo

A gastroscopy will help your doctor to confirm or rule out suspected medical conditions. These include:

- ulcers (in your oesophagus, stomach or first part of your small intestine)

- coeliac disease

- Barrett’s oesophagus

- cancer of the oesophagus or stomach cancer

- anaemia

Your doctor can also use a gastroscopy to give certain treatments, such as:

- stopping bleeding

- removing small growths

- removing objects stuck in your throat or oesophagus or stomach

- widening your oesophagus if it has become narrowed

Aftercare following a gastroscopy

If you had a sedative, you’ll need to rest in a recovery area until the effects of the sedative have passed. You’ll be able to go home when you feel ready, usually after about an hour. You will need someone to drive you home.

If you had a local anaesthetic throat spray, you won’t be able to eat or drink until it wears off. This usually takes around an hour. After that you can eat normally.

Before you leave the hospital, you’ll be given advice about your recovery. This will include what to do if you have any problems. It’s OK to ask questions if you have any concerns.

Your doctor or specialist nurse may explain the findings of your gastroscopy to you before you leave. You may find it best to have a friend or family member there to listen too, particularly if you had a sedative, as it can affect your memory.

Ask your doctor or specialist nurse how and when you’ll get your results. You may get a date for a follow-up appointment to discuss the findings in more detail. Your results will be sent as a report or in a letter to your GP and a copy of this should be given to you. It can take up to two weeks to get results from a biopsy, if one was taken during your gastroscopy.

Recovering following a gastroscopy

After your gastroscopy, you may have a slight sore throat, which can last for a few days.

If you’ve had a sedative, you must not drive, drink alcohol, operate machinery or sign legal documents for 24 hours. It’s best to have a friend or relative stay with you overnight.

Most people have no problems after a gastroscopy. But seek medical attention immediately if you:

- cough up or vomit blood (which may look like coffee grounds)

- have blood in your poo or black tar-like poo

- have severe pain in your tummy or pain that gets worse

- have a raised temperature

If you have any of these symptoms, tell the doctor you see that you have recently had a gastroscopy.

Side-effects of gastroscopy

After having a gastroscopy, you may feel bloated and have some tummy discomfort for an hour or two. Another gastroscopy side-effect is a sore throat, which may last for a few days. This is normal.

Complications of gastroscopy

Complications are problems that happen during or after a procedure. Very few people have complications from a gastroscopy.

When complications do happen, they may include the following.

- Difficulty breathing or heart problems caused by a reaction to the sedative.

- Bleeding from where a biopsy is taken or a small growth removed. This may stop on its own or you may need treatment in hospital to stop the bleeding.

- Damage or tears to your throat, oesophagus, stomach or duodenum. This is rare, but if it happens, you may need an operation to repair the damage.

Complications are more likely if you’re having a treatment during your gastroscopy.

Ask your doctor how these risks might apply to you.

Alternatives to gastroscopy

The alternative to a gastroscopy is a test called a barium swallow and meal. For this test, you drink a liquid that coats the inside of your oesophagus and stomach and shows up on X-rays.

A barium swallow and meal gives less information than a gastroscopy and may miss problems. And it doesn’t let your doctor take a sample of any abnormal tissue they might see. If you have a gastroscopy, your doctor can take a biopsy if necessary.

Your doctor will tell you if a barium swallow and meal or a gastroscopy is the best option for you.

Your doctor will take some steps to help stop you gagging during a gastroscopy. They may spray a local anaesthetic on to the back of your throat to numb the area. This will help to reduce gagging as the gastroscope passes down your throat. And you may have a sedative to help you relax.

See our Gastroscopy procedure section for more information.

A gastroscopy can treat certain conditions. Your doctor can pass instruments down the gastroscope to treat your oesophagus, stomach or duodenum. Treatments you may have during a gastroscopy include stopping bleeding, for example from an ulcer, or removing small benign growths (polyps).

See our uses of gastroscopy section for more information.

A gastroscopy can test for different conditions that might be causing certain symptoms. For example, to find out why you have difficulty swallowing, or why you have pain in your chest or upper tummy. A gastroscopy can also help to confirm or rule out medical conditions, such as ulcers or coeliac disease.

See our uses of gastroscopy section for more information.

When your doctor or nurse passes the gastroscope into your oesophagus and down towards your stomach, it may be uncomfortable for a few seconds. But your doctor or nurse will give you a local anaesthetic or sedation or both. The local anaesthetic will numb your throat, while a sedative will make you drowsy and more relaxed.

See our Gastroscopy procedure section for more information.

You won’t usually have a general anaesthetic so will be awake during a gastroscopy. Most people have a local anaesthetic or sedation or both. But if you think you need a general anaesthetic, it may be possible. Talk to your doctor or specialist nurse about your options and what’s best for you.

See our Gastroscopy procedure section for more information.

Barium swallow and meal

A barium swallow and meal is a type of X-ray test. It allows your doctor to examine your throat, oesophagus, stomach and the first part of your bowel.

Indigestion

Indigestion medicines can be used to relieve pain or discomfort in your upper abdomen (tummy) or chest that may occur soon after meals.

Barrett's oesophagus

Barrett's oesophagus is when the cells that line the lower part of your oesophagus get damaged by acid and bile travelling upwards from your stomach.

Stomach cancer

Did our Gastroscopy information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Gastroscopy. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 9 September 2022

- Ahlawat R, Hoilat GJ, Ross AB. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 14 August 2022

- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Patient. patient.info, last updated 10 February 2022

- Upper gastrointestinal surgery. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published November 2021

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 4 February 2022

- Mallory–Weiss tear. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 16 May 2023

- Endoscopy. MSD Manual. www.msdmanuals.com, reviewed/revised March 2023

- Sedation explained. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published June 2021

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 18 May 2023

- Upper GI X-ray. Radiological Society of North America. www.radiologyinfo.org, reviewed 15 April 2022