Peptic ulcers

Your health expert: Dr Rehan Haidry, Consultant Gastroenterologist

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor, September 2023

Next review due September 2026

Peptic ulcers are sores that can develop on the lining of your stomach, small bowel or food pipe (oesophagus). They usually occur when your stomach acid damages the lining. If you get peptic ulcer treatment as soon as possible, it will reduce the risk of complications.

How a peptic ulcer develops

How a peptic ulcer develops | Watch in 1:45 minutes

Peptic ulcers are sores that can develop in your gastrointestinal tract and stomach. Our animation shows how a peptic ulcer develops.

This animation will show how a peptic ulcer develops.

A peptic ulcer is a roughened area or cavity which is found in the stomach or small bowel.

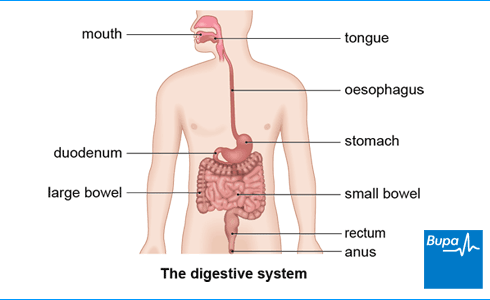

Here in the animation, we show the digestive system peptic ulcers can occur in the stomach or the first part of the small bowel which is called the duodenum.

The stomach produces acid to break down food.

The stomach and duodenum have a layer of mucus which protects it so the stomach acid doesn't damage it,.

A peptic ulcer occurs when the inside of the stomach or small bowel is damaged by the acid it attacks the tissue causing a lesion or ulcer to form the body's usual mechanisms which protect the tissue lining the stomach and duodenum are not working properly.

Here in the animation, we show what a peptic ulcer looks like in the stomach.

Peptic ulcers are usually about one to two centimetres across, they look like large mouth ulcers.

Sometimes the ulcer can erode the stomach wall and cause it to bleed.

Rarely the ulcer may cause a hole to form this can cause severe pain and is a medical emergency.

About peptic ulcers

Your gastrointestinal (GI) tract is made up of your food pipe (oesophagus), stomach and bowels (intestines). It’s where you break down and absorb food. You can develop peptic ulcers when the protective lining of this tract – called the mucosa – is damaged or inflamed.

Normally, the GI tract lining protects itself from the stomach acid that helps you digest food. But if the amount of acid increases or the lining is weakened, the acid can damage your upper GI tract. This can then cause a peptic ulcer.

People of all ages can get peptic ulcers, but they’re more common in older people.

Types of peptic ulcers

Peptic ulcers can occur in various parts of your GI tract. So they may be:

- oesophageal (along the tube that carries food from your mouth into your stomach)

- gastric (in your stomach)

- duodenal (in the first part of your small bowel, where food goes when it leaves your stomach)

Causes of peptic ulcers

There are two main causes of peptic ulcers:

- an infection caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria

- taking medicines such as ibuprofen and aspirin, which irritate the lining of your digestive tract

Helicobacter pylori

This stomach infection is the most common cause of peptic ulcers. Lots of people in the UK are infected with H. pylori and it doesn’t generally cause problems. You may get it from other people or through food.

H. pylori infection causes around nine out of 10 duodenal ulcers and eight out of 10 stomach ulcers. The infection damages the lining of your GI tract by causing:

- inflammation

- causing your stomach to produce too much acid – H. pylori can disrupt the mechanism that switches acid production off

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The second most common cause of a peptic ulcer is regularly taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, over a long time. Along with aspirin, they’re the main medicines associated with peptic ulcers. Taking them also increases the risk of having complications from your ulcer.

It’s safe for most people to take NSAIDs, but up to one in three people have problems if they take them regularly. You’re more likely to develop an ulcer if you’re older, take multiple NSAIDs or have used NSAIDs for a long time.

Other causes

Other things that may increase your risk of an ulcer include:

- other members of your family having an ulcer

- smoking

- drinking alcohol

- getting older

- having a stay in hospital intensive care

- taking medicines, including bisphosphonates (used to treat osteoporosis) and steroids

- infections and conditions such as HIV and Crohn’s disease

- recreational drugs such as crack cocaine

- rare types of tumour

Symptoms of peptic ulcers

You may not have any peptic ulcer symptoms at first. You’re more likely to have what’s called a ‘silent ulcer’ if you’re:

- male

- older

- smoke

- taking NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen

- have a Helicobacter pylori infection

If you do have peptic ulcer symptoms, a common one is tummy (abdominal) pain or discomfort. You may also have pain in your back. Where and when you have pain depends on whether your peptic ulcer is oesophageal, gastric or duodenal.

- If you have a duodenal ulcer (at the start of your small bowel), the pain tends to come on a couple of hours after a meal. Generally, it goes away when you eat again. You may also have pain that wakes you up at night when you have an empty stomach.

- A gastric ulcer (in your stomach) generally causes pain shortly after you eat. Lying flat may relieve it.

- An oesophageal ulcer (in the tube that carries food to your stomach) may cause tummy or lower chest pain and make it difficult to swallow.

Indigestion is often a sign of a peptic ulcer.

Some symptoms may mean you have peptic ulcer complications. Or they can be caused by another health condition, including cancer. See your GP urgently if you:

- are losing weight without dieting

- see blood in your vomit or your poo or if either your vomit or poo are black

- are very tired because this may be caused by anaemia

- have trouble or pain swallowing

- feel full or sore soon after you’ve started eating

Diagnosis of peptic ulcers

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and medical history. They may also feel your tummy, to check for tenderness or pain. Tell your GP if you regularly take over-the-counter painkillers such as aspirin and ibuprofen regularly.

Helicobacter pylori tests

There are different types of test that can show whether or not you have a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

- Stool test – a small sample of your poo (about the size of a pea) is tested for H. pylori.

- Blood test – you’ll give a small blood sample, and your GP will send this to a lab to test for antibodies against H. pylori. Antibodies are produced by your immune system when it detects something that may be harmful. If you’ve been treated for an H. pylori infection before, you won’t have a blood test.

- Breath test – in this hospital test, you swallow a liquid that contains a harmless radioactive chemical. If you’re infected, this chemical will be broken down by H. pylori bacteria to produce carbon dioxide gas. After drinking the liquid, the level of radioactivity in your breath is measured and can show if you’re infected with H. pylori.

Endoscopy

Your doctor may refer you for an endoscopy (also called a gastroscopy)to examine the inside of your stomach and duodenum. You may have this if you’re over 55 and:

- you regularly use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen

- you’ve had a stomach ulcer before

- someone in your family has had stomach cancer

Whatever your age, your GP may suggest an endoscopy if you’ve got symptoms such as:

- anaemia (low red blood cell count)

- difficulty swallowing

- unexplained weight loss

- persistent vomiting (being sick)

Your doctor may arrange for you to have the procedure straightaway if you have any complications – for example, vomiting blood.

If your doctor sees signs of an ulcer, they’ll take a tissue sample (a biopsy). This is tested to see if your ulcer is caused by H. pylori. They’ll also check to see if the ulcerated area is cancerous, although cancer is rare. See our FAQs for more information about peptic ulcers and cancer.

Looking for prompt access to quality care?

With our health insurance, if you develop new conditions in the future, you could get the help you need as quickly as possible, from treatment through to aftercare.

To get a quote or to make an enquiry, call us on 0800 600 500∧

Self-help for peptic ulcers

There are helpful lifestyle changes you can make if you have a peptic ulcer. Smoking can cause a peptic ulcer or make it worse. So if you smoke, try to quit because this may help your symptoms. Alcohol may also increase your risk of a peptic ulcer. So if you cut down, that may help too.

Keep to a healthy weight because if you’re overweight, it can make your symptoms worse.

Try to avoid triggers (foods that make your symptoms worse). You may find Keeping a diary (PDF, 1.36 MB) of what you’ve eaten and when you have symptoms helps to identify triggers. They can vary between people, but common triggers are:

- spicy foods

- fatty foods

- chocolate

- tomatoes

- coffee

Other things that may help include:

- eating smaller portions

- having your evening meal at least three hours before you go to bed

If you need to take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, particularly long-term, ask for your GP advice. They’ll help you to reduce your risk of developing a peptic ulcer.

Treatment of peptic ulcers

It’s important to get the right treatment if you’re diagnosed with a peptic ulcer. If treated properly, duodenal ulcers will heal in around four weeks and stomach ulcers in eight weeks.

If you treat the underlying cause, it will lower the chance of your ulcer coming back. This usually means getting rid of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) or stopping taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Medicines

You can take antacids to help relieve indigestion and other symptoms. Your GP will usually prescribe a medicine called a PPI (proton-pump inhibitor) to reduce the amount of acid your stomach produces. Like most medicines, these can cause potential side-effects, including diarrhoea or feeling sick.

Your doctor may also prescribe medicines to treat the cause of your peptic ulcer.

H. pylori-related ulcers

If your peptic ulcer is caused by an H. pylori infection, a course of two different antibiotics will usually clear the infection. You take these for a week.

If you take PPI medicines alongside the antibiotics, it will help to prevent further damage to your gastro-intestinal (GI) tract and give your ulcer a chance to heal. If PPIs don’t work well for you, your doctor may prescribe a medicine called an H2-receptor antagonist.

NSAID-related ulcers

If your ulcer is caused by taking NSAIDs, your doctor may ask you to stop, so your ulcer can heal. They’ll also give you a PPI to decrease acid production.

Your GP may suggest an alternative painkiller or different type of NSAID that’s less likely to cause an ulcer. But they’ll explain your options.

Follow-up

Your doctor will monitor you to check that your ulcer is healing. If it was caused by H. pylori, they’ll need to check that the infection has cleared up. You’ll have H. pylori tests again if they previously showed this was the cause of your ulcer.

If you had a stomach ulcer, you’ll have another endoscopy to make sure everything has healed. If you had a duodenal ulcer, you won’t usually need an endoscopy.

Your GP may refer you to a specialist if your ulcer doesn’t respond to treatment or keeps coming back.

Complications of peptic ulcers

If you have treatment for a peptic ulcer, complications aren’t very common. But they still may develop, particularly if you’re older and taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or medicines that stop your blood clotting such as aspirin or warfarin. It’s important to be aware of complications because they can be life-threatening. Complications include the following.

Bleeding

If your ulcer grows into (erodes) any underlying arteries or veins (blood vessels) it can cause bleeding. If your ulcer is bleeding, you may:

- throw up (vomit) blood – this can be bright red or dark like coffee grounds

- pass poo that’s black and sticky

- develop iron-deficiency anaemia if you’ve been losing blood for some time

Get urgent medical help if you have any of these symptoms. A specialist doctor (gastroenterologist) may be able to stop the bleeding using an endoscope. You may need emergency surgery, but this will depend on how much blood you’ve lost.

Perforation

If your ulcer eats through the lining of your stomach or duodenum, you may develop a perforation. Perforation means the ulcer has broken through the wall of your stomach or duodenum, and caused inflammation of your tummy lining (peritonitis) and a potentially serious infection. Your stomach will feel rigid and sore. Go to an accident and emergency department if you think this has happened because you may need emergency surgery.

Obstruction

Obstruction means that food is blocked from passing from your stomach into your duodenum during digestion. This is called pyloric stenosis. It’s rare but can happen if scar tissue develops around your ulcer. Obstruction may cause you to:

- feel and be sick

- lose weight

- become dehydrated

Depending on the cause of the obstruction, it can be treated in an endoscopy or with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) or by surgery.

A peptic ulcer is a sore that can develop on the lining of your stomach, small bowel or food pipe (oesophagus). It is usually the result of damage to the lining from stomach acid. You can get a peptic ulcer at any age, but they’re more common in older people.

For more information, see our section on about peptic ulcers.

The two main causes of peptic ulcers are:

- an infection by a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

- medicines such as ibuprofen, which can irritate the lining of your gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Your GI tract is made up of your food pipe (oesophagus), stomach and bowels (intestines). It’s where you break down and absorb food.

For more information, see our section on causes of peptic ulcers.

Peptic ulcers don’t turn into or cause cancer. But certain things can increase the risk of both peptic ulcers and cancer. These include smoking, an H. pylori infection, and diet. So if you have an ulcer, you may have an increased risk of stomach cancer or oesophageal cancer. Some peptic ulcer symptoms such as indigestion, unexplained weight loss, vomiting and problems swallowing, can also be signs of stomach cancer and oesophageal cancer. Your doctor will look for signs of cancer during your endoscopy and they may take a biopsy.

For more information, see our section on diagnosis of peptic ulcers.

A peptic ulcer can be diagnosed with some tests. First, your doctor will test if you have a Helicobacter pylori infection. They may do this by testing a small sample of your poo or your blood, but there are other ways to test. You may also need to have an endoscopy (gastroscopy) to examine the inside of your stomach and duodenum.

For more information, see our section on diagnosis of peptic ulcers.

Stress can contribute to a peptic ulcer forming and may make your symptoms worse but emotional stress cannot directly cause it. It’s important to take some steps to reduce your stress. You may find it helpful to have a talking therapy or help from your doctor to treat depression.

Anxiety can make the symptoms of a stomach ulcer worse but it can’t directly cause it. Make sure you get help to reduce anxiety. Relaxation therapies may help. Or talking therapies may work for you – ask your doctor for advice on how to access support.

Gastroscopy

A gastroscopy is a procedure that allows a doctor to look inside your oesophagus , your stomach and part of your small intestine.

Tips for a healthy and well-balanced diet

A healthy, well-balanced diet involves eating foods from a variety of food groups to get the nutrients that your body needs to function.

Over-the-counter painkillers

Effects of smoking

Did our Peptic ulcers information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Peptic ulcer disease. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Peptic ulcer disease. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 10 June 2023

- Peptic ulcer disease. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 26 April 2021

- Gastrointestinal conditions. Oxford Handbook of Adult Nursing. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published June 2018

- Chiejina M, Samant H. Esophageal ulcer. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, last updated 12 February 2023

- Gastrointestinal medicine. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published June 2020

- Upper gastrointestinal surgery. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery. Oxford Academic. academic.oup.com, published November 2021

- Helicobacter pylori infection. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Helicobacter pylori. Patient. patient.info, last updated 26 May 2020

- Dyspepsia – proven peptic ulcer. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised July 2023

- Peptic ulcer disease. Patient. patient.info, last updated 26 May 2020

- Gastrointestinal tract (upper) cancers – recognition and referral: Symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal tract (upper) cancers. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised February 2021

- Symptoms of stomach cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 30 June 2022

- Test and treat for Helicobacter pylori (HP) in dyspepsia. Public Health England. www.gov.uk, last updated 5 September 2019

- Antibody summary. Encyclopaedia Britannica. www.britannica.com, accessed 11 July 2023

- Helicobacter pylori infection. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 21 July 2021

- Proton pump inhibitors. Nice British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Risks and causes of stomach cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 31 August 2022

- Risks and causes of oesophageal cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 15 August 2023

- Symptoms of oesophageal cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 14 August 2023