Heart valve surgery

- Professor Olaf Wendler, Professor of Cardiac Surgery and Chair of the Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute at Cleveland Clinic London

Heart valve surgery is an operation to fix or replace leaking, narrowed or infected heart valves. It may ease the symptoms of heart valve disease and stop permanent damage to your heart.

Heart valve replacement

Animation | Heart valve replacement| Watch in 1:37 minutes

Discover what happens during heart valve replacement surgery.

About heart valve surgery

You may need heart valve surgery if there’s a problem with one or more of your heart valves. Heart valves control the blood flow in to and out of your heart. Damaged or faulty valves can affect how well your heart pumps blood around your body.

Your valves may:

- be narrow or tight (called stenosis)

- not close properly and leak (called regurgitation)

If there’s a problem with your heart valves, you may not have any symptoms at first. You’ll usually only have surgery if your heart valves are badly damaged or causing symptoms. Heart valve surgery can ease your symptoms and improve your quality of life.

In open-heart valve surgery, the surgeon opens your chest using keyhole surgery. They make a small cut in your breastbone or from the right side of your chest to reach your heart. If you need more complicated surgery, your surgeon may cut your whole breastbone. Your surgeon may recommend another procedure instead. This will depend on many things, including how well you are.

Here we talk about what happens in open-heart surgery.

Types of heart valve surgery

Your surgeon will usually recommend repairing your damaged or faulty valves before replacing them. But this may depend on your age, what’s wrong with your valves and if you have any other medical conditions. Both repairing and replacing your heart valves involve surgery.

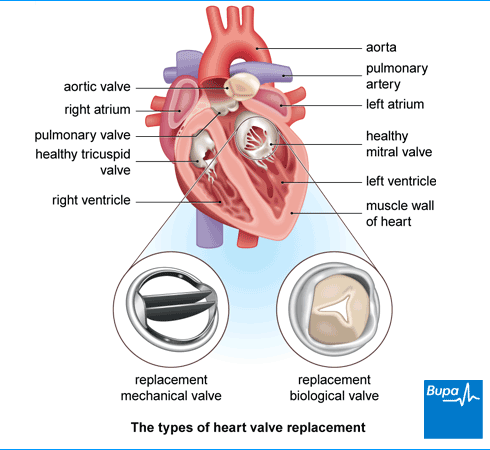

If your valves can’t be repaired, they’ll be replaced with prosthetic (artificial) valves. There are two main types of prosthetic valve.

- Mechanical valves. These are made from carbon and metal and last for a very long time. If you have this type of valve, you’ll need to take blood thinning medicines (anticoagulants) for the rest of your life. This is to prevent blood clots forming on the valves.

- Tissue (biological or bioprosthetic) valves. These are usually made from animal (pig or cow) tissue and wear out faster than mechanical valves. They are usually replaced after 10 to 15 years. You don’t need to take life-long blood-thinning medicines with this type of valve.

Your surgeon will discuss the pros and cons of each type of valve and which one is best for you.

Preparing for heart valve surgery

Heart valve surgery is usually done in a specialist centre where heart surgeons work. There may not be suitable facilities locally, so you may not be able to have the surgery at your local hospital.

You’ll need to prepare before you go into hospital. Many people are in hospital for about a week after heart valve surgery. It may take you up to three months to fully recover at home. You won’t be able to drive for at least a month after your surgery. So, you may need to arrange for family or friends to help with things like cooking, shopping and cleaning. If you can, it’s a good idea to stock your freezer with some pre-prepared meals. For more information, see our section: Recovering from heart valve surgery.

Your surgeon will explain how to prepare for your operation. If you smoke, you’ll be strongly advised to stop. This is because smoking makes you more likely to get a chest or wound infection after surgery. This can mean you recover more slowly from your operation.

You’ll have your heart valve surgery under general anaesthesia. This means you’ll be asleep during the operation. A general anaesthetic can make you sick, so you need to have an empty stomach before you have a general anaesthetic. This is why it’s important that you don’t eat or drink anything before surgery. Follow your anaesthetist or surgeon’s advice – if you have any questions, just ask.

You’ll need to wear compression stockings to keep your blood flowing. This will help to stop blood clots forming in the veins in your legs. You may need to have an injection of an anti-clotting medicine (or tablets) as well.

Your surgeon will discuss with you what will happen before, during and after your surgery. If you’re unsure about anything, don’t be afraid to ask. No question is too small. It’s important that you feel fully informed and are happy to give your consent for the operation to go ahead. You’ll be asked to do this by signing a consent form.

What are the alternatives to heart valve surgery?

If you have mild-to-moderate heart valve disease, you may not have any symptoms. Your doctors will keep monitoring your valves and how well your heart works. But if you start getting symptoms from your heart valve problem, you may need to have a repair or replacement.

If you have a faulty heart valve, you may be able to take medication to ease your symptoms. But these medicines won’t fix the problem with your valve.

Other types of heart valve procedure

You’ll usually have open-heart valve surgery, but this may depend on your overall health. Your surgeon will discuss the available options with you.

If you can’t have or don’t need open-heart valve surgery, you may have one of these two types of percutaneous heart valve therapy.

- Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Your surgeon will pass a tube through a blood vessel in your groin or neck to replace or repair your heart valve. They may offer this procedure if you’re not well enough to have open-heart valve surgery.

- Edge-to-edge repair. A device is clipped onto a failing mitral valve in your heart to make it work better. Your surgeon can do this without cutting into your breastbone.

What happens during open-heart valve surgery?

Your surgeon will open your chest. They may make a small cut down the middle of your breastbone (sternum) or to one side of your chest to reach your heart. Or they may make a bigger cut down your breastbone. Your heart can’t work properly during the operation, so you’ll be linked up to a bypass machine. This will make sure that blood is still being pumped around your body.

During surgery, your surgeon may be able to:

- repair your valve if it isn’t too badly damaged

- replace your valve with a mechanical valve or a tissue (biological or bioprosthetic) valve

After your operation, your surgeon will join up your breastbone using wires. They’ll then close the skin on your chest with dissolvable stitches.

What to expect afterwards

After your operation, you may be taken to the hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU) or high dependency unit (HDU). When you wake up, you’ll be connected to machines that record the activity of your heart, lungs and other body systems. You may need a ventilator to help you breathe. When your medical team are happy that you’re recovering safely, they’ll move you to a surgical ward.

You’ll need pain relief as the anaesthetic wears off. You may be given patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) once you wake up. A PCA pump is connected to a drip in your arm – you use it to control how much pain-relief medicine you have.

You’ll be encouraged to get out of bed and move around as soon as possible. This will help to prevent chest infections and blood clots in your legs. A physiotherapist will visit you regularly after the operation to advise you on exercises to help your recovery.

You’ll be able to go home when you and your surgeon feel you’re ready. Many people are in hospital for around a week after heart valve surgery. Make sure someone can take you home and stay with you for a day or so.

Before you go home, your nurse will give you advice about caring for your healing wounds. You may be given a date for a follow-up appointment.

If you have wires in your breastbone from the operation, these will be permanent, but may be taken out six months after surgery if needed. The dissolvable stitches your surgeon used to close your skin wound don’t need to be removed. They will slowly dissolve over several weeks.

Recovering from heart valve surgery

Heart valve surgery recovery can take two to three months. You’ll need to build up your activities slowly to get back to normal. Everyone recovers differently, so speak to your surgeon about when you can go back to work and your other usual activities.

After your surgery, your doctor may recommend you take part in a cardiac rehabilitation programme. This programme will give you advice on:

- healthy eating

- how to manage stress

- stopping smoking (if you smoke)

- taking medicines

- staying at a healthy weight

- keeping active

If your heart valve disease was caused by coronary heart disease, making lifestyle changes may stop this getting worse.

Tell your dentist that you’ve recently had heart valve surgery. It’s important to look after your teeth and gums too. Sometimes when you have dental treatment, bacteria can get into your blood from your mouth. This could lead to an infection of your heart valve. If the infection spreads to your heart, this can be serious – it’s called endocarditis. For more information, see our section: Complications of heart valve surgery.

You shouldn’t drive for at least a month after your surgery. You don’t need to tell the DVLA unless you drive a bus, coach, or lorry. But don’t start driving again until you’ve checked with your surgeon. It’s a good idea to check your motor insurance policy too.

After open-heart surgery, it may be safe for you to fly after about 10 days. But this will depend on which type of surgery you’ve had and how well you’re recovering. Ask your surgeon for advice. You should also check your airline’s policy.

Contact the surgical ward if you have:

- increasing tenderness or redness round your wound

- persistent bleeding or pus coming from your wound

- a high temperature or fever, especially if you’re losing weight or not feeling hungry

- new or severe heart palpitations (a sensation of a skipping or thumping heartbeat)

- difficulty breathing

- chest pain that’s different from the pain in your wound

Remember you’ve been through a major operation, so expect to have good days and less good days. Be kind to yourself and accept help where it’s offered. Don’t worry if your progress seems slow – you’ll gradually get back to your normal activities and feel well again.

Medicines after heart valve surgery

Talk to your surgeon about which medicines you need to take after your operation.

If you have a mechanical valve replacement, you’ll need to take a blood thinning medicine. This type of medicine is called an anticoagulant – the most common one is warfarin. You’ll need to take this for the rest of your life to stop blood clots forming around your new valve.

If you have a tissue (biological) valve replacement, you usually only need to take anticoagulant medicines for a few months after your operation.

While you’re taking anticoagulants (warfarin), you’ll need to have regular blood tests. These are important to check you’re on the right dose. Some other medicines can stop blood-thinning medicines from working so well. Drinking a lot of alcohol may stop them working well too. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine. And speak to your pharmacist if you have any questions.

Exercising after heart valve surgery

Your physiotherapist or nurse will usually help you to start moving within a couple of days after your surgery. This will help your recovery. After a few days, you can start to increase how much exercise you do. Gentle walking is the best way to begin. Walking after surgery is recommended at least twice a day for 10 to 15 minutes to start with. You can expand this to 30 minutes over the first four to six weeks.

Don’t do any strenuous or vigorous activity straight away because it may put a strain on your heart. If your surgeon cut through your breastbone (sternum) during your operation, don’t do any heavy lifting for around 12 weeks after surgery. This will give your bone time to heal. But ask your surgeon for guidance as this may vary from person to person.

Stop exercising straightaway if you feel:

- any pain or tightness in your chest

- dizzy or faint

- your heart beating irregularly

- short of breath

If you get any of these symptoms, stop exercising and seek medical advice.

Side-effects of heart valve surgery

It’s normal to get some side-effects after heart surgery. Everyone responds differently, but afterwards you may:

- have some fluid leaking from your wound

- feel some discomfort in your chest and in the muscles of your shoulders, back or neck

- feel very tired

- not feel hungry

- feel emotional and upset

- get constipated (this may be because of the painkillers you’re taking)

- find it hard to sleep at night

- notice a ticking noise in your chest if you’ve had a mechanical valve replacement (you’ll get used to this after a while)

- have a small lump at the top of your wound – this may feel numb and itchy but will go down and ease as it slowly heals

If you’re worried about these or any other symptoms, contact your GP.

Complications of heart valve surgery

All medical procedures carry some risks. Your surgeon will explain these to you when discussing your options. Complications are when problems happen during or after the procedure. Possible complications of heart valve surgery may include:

- bleeding

- an infection

- blood clots

- heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmia)

- problems with your kidneys

- stroke

If you have a heart valve repaired or replaced, it can get infected. The infection can spread to the lining of your heart. This is called endocarditis and is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition. Endocarditis is usually treated with antibiotics. But if the infection affects the new heart valve, you may need to have repeat surgery.

Gentle exercise such as walking will help you recover. But don’t do any strenuous or vigorous activity straight away because this may put pressure on your heart. Speak to your physiotherapist, doctor or cardio rehab team about the safest way to exercise. For more information, see our section: Recovering from heart valve surgery.

You may feel worse in the first few weeks while you recover from surgery. But then the positive effects of the surgery should kick in. If your faulty heart valve was causing symptoms, repairing or replacing it should ease these symptoms and improve your quality of life.

Heart valve disease

Heart valve disease is when one or more of your heart valves become diseased or damaged, affecting the way that blood flows through your heart.

How to take care of your surgical wound

Other helpful websites

Did our Heart valve surgery information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Aortic valve surgery. Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery. scts.org, accessed December 2024

- Heart disease. ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2018

- Aortic valve anatomy. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated November 2024

- Aortic stenosis. ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2018

- Aortic stenosis. Patient. patient.info, last edited December 2021

- Mitral regurgitation. Patient. patient.info, last edited January 2023

- Cardiothoracic surgery. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery. 5th ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online November 2021

- Heart valve surgery. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, last reviewed June 2024

- Anticoagulants. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated December 2021

- Cardiovascular. Oxford Handbook of Geriatric Medicine. rd3 ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online February 2018

- Baumgartner H, Volkmar Falk V, Jeroen J Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38(36):2739–91. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391

- Preparing for surgery. Fitter Better Sooner. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published November 2024

- Heart valve disease or replacement valve and driving. GOV.UK. www.gov.uk, accessed January 2022

- Your anaesthetic for heart surgery. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published September 2023

- You and your anaesthetic. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published April 2023

- Your anaesthetic for major surgery. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published April 2023

- Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed June 2023

- Good surgical practice. The Royal College of Surgeons. www.rcseng.ac.uk, published September 2014

- Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline NG 208. nice.org.uk, published November 2021

- Transcatheter aortic valve implant (TAVI). Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery. scts.org, accessed January 2022

- Ansari MT, et al. Mitral valve clip for treatment of mitral regurgitation: an evidenced-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2015 May 1; 15(12):1–104

- Cardiothoracic surgery. Oxford Handbook of Operative Surgery. 3rd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online May 2017

- Principles of surgery. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery. 5th ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online November 2021

- Pain. Adult Handbook of Adult Nursing. 2nd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2018

- Surgery. Adult Handbook of Adult Nursing. 2nd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2018

- Caring for someone recovering from a general anaesthetic or sedation. 2nd ed. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published November 2021

- General surgery. Oxford Handbook of Operative Surgery. 3rd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online May 2017

- Cardiac rehabilitation: a national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). www.sign.ac.uk, published July 2017

- Cardiac rehabilitation. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed May 2016

- Cardiovascular disease: Information for Health Professionals on assessing fitness to fly. Civil Aviation Authority. www.caa.co.uk, accessed January 2025

- I have recently had surgery. Civil Aviation Authority. www.caa.co.uk, accessed January 2025

- Prevention of infective endocarditis. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed July 2023

- Infective endocarditis. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed November 2021

- Heart disease. ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford Medicine Online. oxfordmedicine.com, published online June 2018

- Interactions. Warfarin. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated December 2021

- Having heart surgery. www.bhf.org.uk, published May 2018

- Anaesthesia explained. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published March 2021

- Common postoperative complications. Patient. patient.info, last reviewed November 2020

- Personal communication. Professor Olaf Wendler. Professor of Cardiac Surgery. August 2022

- Victoria Goldman, Freelance Health Editor