Jaw joint problems

Your health expert: Mr Nabeel Bhatti, Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Content editor review by Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor, August 2023

Next review due August 2026

Jaw joint problems affect how well your jaw works. Your jaw joint is called the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Problems with your TMJ can make your jaw feel sore and can cause headaches and ear pain too. TMJ problems usually get better on their own.

About jaw joint problems

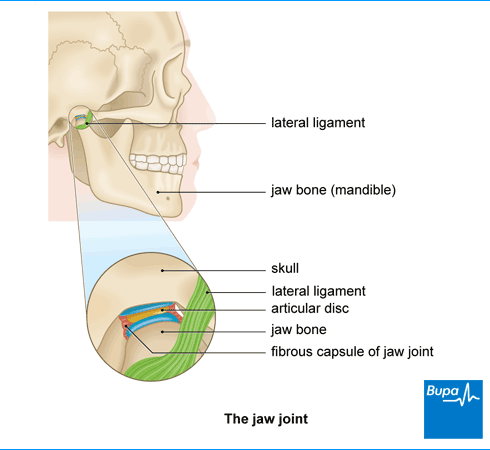

Your jaw joint (temporomandibular joint or TMJ) connects your lower jaw (mandible) to your skull. It allows your mouth to open and close so you can speak and chew. Lots of muscles and ligaments help your jaw move up and down, from side to side, and backwards and forwards.

If you have a problem with your jaw joint or the muscles around it, this is usually called temporomandibular jaw disorder.

You can get problems with your jaw at any age, but it’s most likely to happen when you’re between 20 and 40.

Causes of jaw joint problems

Doctors don’t know exactly what causes jaw joint problems, and why some people are more likely than others to get problems. But you may be more likely to get jaw joint problems if you:

- have injured your jaw

- have had recent dental treatment (such as having your wisdom teeth removed)

- have knocked or fallen on your chin

- stretch your jaw too much when you yawn, for example

- clench your jaw or grind your teeth (bruxism)

Stress, depression and anxiety don’t directly cause jaw joint problems, but they may make jaw joint problems worse. This is because you may be more likely to grind your teeth. For example, during times of stress, you might grind your teeth at night or while you’re concentrating without realising. But, if you grind your teeth, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll have jaw joint problems.

Some people with jaw joint problems have other chronic health conditions (conditions that last longer than three months), such as:

- fibromyalgia

- irritable bowel syndrome

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- migraine

- rheumatoid arthritis

These chronic conditions may affect how well your muscles and joints work or how your body reacts to pain. Other things that can affect your jaw joint include the following.

- Disc displacement. This means the thin disc inside your jaw joint is in the wrong place. It can happen if you dislocate or hurt your jaw. When you move your jaw, you may hear noises such as clicking, grating, or popping.

- General wear and tear from teeth grinding, for example.

- Arthritis. Osteoarthritis may affect your jaw joint, as can rheumatoid arthritis.

Symptoms of jaw joint problems

If you have a problem with your jaw joint, you may:

- have a dull aching pain around your jaw, cheek, ear, or neck

- find it hard to move your jaw when you try to speak or chew

- feel like your jaw is locked in position when you try to open your mouth (lock jaw)

- find it hard to open your mouth wide or close it easily

- hear popping, grating or clicking sounds when you move your jaw

- get headaches

- get ear pain, tinnitus (sounds in your ears), and dizziness

- notice your bite (when you put your teeth together) doesn’t feel as comfortable as usual

- have toothache, which is likely because you’re grinding your teeth at night, or clenching your jaw

You may find that your jaw pain gets worse during the day or when you chew or talk. You may be able to manage these symptoms at home and they often get better on their own. But if you’re worried about the pain or your symptoms are getting worse, make an appointment with your dentist to find out if treatment could help.

Diagnosis of jaw joint problems

If your jaw hurts or doesn’t feel right, see your dentist. They’ll ask about your symptoms and if you have any health problems or long-term medical conditions. Your dentist will then check your head, neck, face and jaw.

They may:

- press around your jaw to see if it’s tender

- ask you to move your jaw in all directions to see how well you can move it

- ask where and when your jaw feels sore as you move it

- listen for clicking noises

- look inside your mouth to see if you have any problems with your teeth or gums

- ask if anything triggers your jaw problems (for example, chewing or yawning)

- check if you grind your teeth or bite your nails because both of these can cause jaw problems

Your dentist can usually diagnose jaw joint problems just by examining your jaw. But sometimes they may want to check if part of your jaw joint is out of place or if you have any signs of arthritis. They may refer you to a specialist doctor such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. You may need to have some tests and scans to check your jaw joint, including:

Self-help

Jaw joint problems often get better on their own after a few months or so. There are lots of things you can do to ease your symptoms.

- Eat soft foods so you don’t have to chew food for long.

- Eat slowly and take small bites of food.

- Stop using your jaw as much as you can when it really hurts.

- Don’t yawn widely, chew gum, pens, or bite your nails.

- Try to stop clenching your jaw or grinding your teeth.

- Try to reduce stress if you can because stress can make jaw clenching or teeth grinding worse. Relaxation techniques, such as mindfulness, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may help.

- Make sure you get plenty of sleep.

- Massage the muscles around your jaw for a minute, four times a day.

- Put an ice pack (or a bag of frozen peas wrapped in a tea towel) or heat pad on your jaw.

- Ask your dentist, doctor or physiotherapist about some jaw-opening (TMJ exercises) you can do.

Treatment of jaw joint problems

If self-help measures don’t ease your symptoms, your dentist or doctor may suggest you try some medicines or other treatments. The best treatment for you will depend on what’s causing your jaw joint problems and how bad they are.

A bite guard

If your jaw joint problem is caused by clenching your jaw or grinding your teeth, your dentist may suggest you wear a bite guard (bite splint), usually at night. This plastic cover fits over your upper or lower teeth and stops them coming into contact with each other. A bite guard may ease your jaw pain but it may not help you to move your jaw more easily.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy may help to ease your symptoms. Jaw-stretching TMJ exercises, massage and changing your posture may help to relax your jaw muscles. For more information, see our FAQ below: Can TMJ exercises help my jaw joint problems?

Medicines

Over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, may help to ease any pain. You can buy these from your local pharmacy. Your pharmacist can help you choose the right one for you. You may be able to take these as tablets. Or you may be able to put a gel containing an anti-inflammatory painkiller, such as ibuprofen, directly onto your jaw.

If you have a lot of TMJ jaw pain, your dentist or doctor may prescribe some stronger medicines. These include the following.

- Benzodiazepines. These relax your muscles and may help to reduce tightness and pain in your jaw. They may also ease anxiety. This may help if stress is causing you to grind or clench your teeth. These medicines can be addictive so your dentist or doctor will only prescribe them for up to two weeks.

- Antidepressants. These can help to ease chronic pain, especially nerve pain. Your doctor or dentist will prescribe the lowest possible dose so you’re less likely to get side-effects.

Surgery

Most people don’t need surgery for jaw joint problems. But if other treatments haven’t worked for you, your dentist may refer you to a specialist. You may see an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or an ear, nose, and throat specialist. Your specialist may suggest surgery if you’re in a lot of pain and your jaw joint is affecting your daily life.

Your surgeon may suggest:

- trying to move your jaw joint into a different position

- a corticosteroid injection into your jaw joint to help ease your pain

- a botulinum toxin (Botox) injection into the muscles that control your jaw to help relax them

- surgery to open your jaw joint so they can operate on the bones, cartilages and ligaments

- using a needle or syringe to clean and take some of the fluid out of your jaw joint

- replacing your jaw joint with an artificial (prosthetic) one

It’s important to discuss the risks and benefits of surgery with your surgeon to see if it’s the right option for you.

Complementary therapies

Some people find acupuncture helps to ease their jaw joint pain. But it doesn’t work for everyone and may only last for a short time. Experts need to do more clinical trials to see how well acupuncture works for jaw pain before they can recommend it.

Physiotherapy services

Our evidence-based physiotherapy services are designed to address a wide range of musculoskeletal conditions, promote recovery, and enhance overall quality of life. Our physiotherapists are specialised in treating orthopaedic, rheumatological, musculoskeletal conditions and sports-related injury by using tools including education and advice, pain management strategies, exercise therapy and manual therapy techniques.

To book or to make an enquiry, call us on 0345 850 8399

TMJ pain usually gets better with time. The symptoms often get better, and with time, any clicking noises will get less. While treatment cannot cure TMJ pain directly, it can improve your symptoms so it doesn’t bother you so much, if at all. Whether you have treatment or not, your symptoms will probably get better.

See our treatment of jaw joint problems section for more information.

There are some signs that you may have a problem with your jaw joint. For example, you may have a dull aching pain around your jaw, cheek, ear, or neck. And you might find it hard to move your jaw when you try to speak or chew. Or your jaw may feel like it’s locked in position when you try to open or close your mouth (lock jaw).

See our symptoms of jaw joint problems section for more information.

TMJ exercises may help jaw joint problems. You may find some exercises help to ease your pain and make your jaw easier to move. Ask your dentist or physiotherapist to show you what exercises to do. And then do them in front of a mirror so you check that you’re doing them properly.

See our self-help for jaw joint problems section for more information.

TMJ problems often go away on their own after a few months or so. And there are things you can do to ease your symptoms in the meantime. For example, eat soft foods so you don’t have to chew food for long, and eat slowly and just take small bites. There are also medicines that may help, such as over-the-counter painkillers like paracetamol or ibuprofen that may help ease any pain.

See our self-help for jaw joint problems section and treatment of jaw joint problems section for more information.

Over-the-counter painkillers

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, affecting over eight million people in the UK. It affects your joints, making them stiff and painful.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are a type of drug that can be used to treat depression and other disorders.

Other helpful websites

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Jaw joint problems information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Temporomandibular disorders. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 26 May 2023

- Temporomandibular disorders (TMDS). NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised August 2021

- Temporomandibular joint syndrome. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 14 January 2022

- Bruxism. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 28 May 2023

- Temporomandibular disorders. Patient. patient.info, last updated 15 December 2020

- Analgesics. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Hypnotics and anxiolytics. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023

- Neuropathic pain. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 31 May 2023