Lymph node removal (lymphadenectomy)

- Mr. Pawel Trapszo, Consultant Breast and Oncoplastic Surgeon

Lymph node removal is a surgical procedure to take out one or more of your lymph nodes. Your doctor may recommend you have this procedure if you’ve been diagnosed with cancer. It can help to check whether cancer has spread to your nearby lymph nodes, or reduce the chance of it coming back.

About lymph node removal

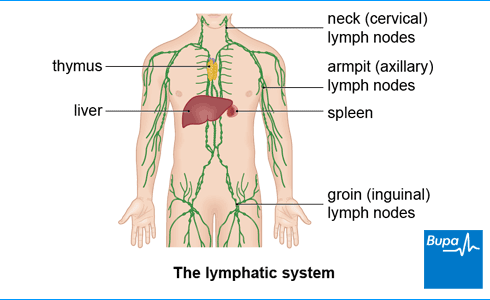

Lymph nodes are small, kidney bean-shaped organs found throughout your body, including in your armpits, neck, and groin. They are part of the lymphatic system. This is a network of thin tubes that carries a clear fluid called lymph, containing waste from cells around your body, back to your bloodstream.

Your lymph nodes help to fight infection and filter lymph fluid. They trap any bacteria and waste products in lymph and destroy old or abnormal cells, such as cancer cells.

Why are lymph nodes removed?

Many types of cancer spread through the lymphatic system and nearby lymph nodes are one of the first places they spread to. If you have cancer, there are two main reasons why your doctor may suggest removing lymph nodes.

- One or more lymph nodes may be removed to check whether your cancer has spread. Knowing this helps your doctor plan the best treatment for you.

- If tests have shown that the cancer has reached your lymph nodes, you may have them taken out to remove the cancer. This helps to reduce the chance of your cancer coming back.

Lymph nodes can often become swollen due to infection, because of autoimmune diseases, and more rarely, cancer. If you have swollen lymph nodes, it doesn’t mean that you’ll necessarily need your lymph nodes removed. Swollen lymph nodes often get better on their own. But if they don’t after a month or so, contact your GP.

Where are lymph nodes removed from?

Where your lymph nodes will be removed from depends on the type of cancer you have. Common areas for lymph node removal include your:

- armpit, for breast cancer

- neck, for head and neck, and thyroid cancers

- groin, for cancers of the penis, anus, and vulva

- tummy (abdomen), for testicular or ovarian cancers

- back passage, for bowel cancer

Surgery to remove lymph nodes may be done at the same time as your main surgery for cancer. Or, it may be done as a separate procedure.

Medical terms used in lymph node removal

You may hear a number of different medical terms used when describing lymph node removal. Here are some of the most common ones and what they mean.

- Lymphadenectomy – the medical term for lymph node removal.

- Lymph node biopsy – just one or two nodes are removed to check for cancer cells.

- Sentinel lymph node – this is the first lymph node your cancer is likely to spread to.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy – removal of the sentinel lymph node. It’s usually done if you have breast cancer or melanoma (skin cancer),as well as gynaecological cancers like cervical cancer and endometrial cancer.

- Lymph node dissection (or clearance) – this is when the lymph nodes in a particular area are removed. An example is axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. In this procedure, your surgeon removes a number of lymph nodes from your armpit (axilla).

Preparation for lymph node removal

Your doctor will talk to you about why they recommend lymph node removal, including the benefits and risks involved. They’ll explain exactly what will happen before, during, and after your procedure. Ask your doctor any questions you have. It’s important that you feel fully informed, as you’ll need to give your consent for the procedure to go ahead.

Getting healthy for surgery

Your doctor or nurse will explain how to prepare for your procedure. They might advise you on things you can do before surgery to improve your general health and make your recovery easier and faster. This might include aiming to get to a healthy weight, being active, and if you smoke, stopping smoking. Smoking increases your risk of getting a chest and wound infection, and slows healing time.

You’ll probably be invited to a pre-admission assessment clinic at the hospital a week or two before your operation. Here, a nurse will do some general checks and tests to make sure you’re well enough for surgery.

Your doctor or nurse will give you advice if you can keep taking any medicines before your surgery. You might need to pause them or switch to another type of medicine.

Preparing for your hospital stay

You will usually need a general anaesthetic, for lymph node removal, especially if you’re having many lymph nodes removed. This means you’ll be asleep during the procedure. With a general anaesthetic, you’ll need to stop eating and drinking for some time beforehand. Your hospital will give you clear instructions on when. It’s important to follow this advice.

Although some lymph node surgeries can be done as a day-case, you will often need to stay in hospital for one or more nights. Your healthcare team should let you know what to expect. If you need to, make arrangements for a stay in hospital and for help at home afterwards.

At the hospital

On the day of your procedure, your surgeon or nurse will check you’re feeling well and happy to go ahead. The staff at the hospital will do any final checks and get you ready for surgery. They may ask you to wear compression stockings, or have an injection of an anticlotting medicines, to help prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

If you’re having a sentinel lymph node biopsy, you may need to have a scan before your operation, to help find the sentinel node. This involves having an injection of a tracer (a radioactive liquid) that can show up on a scan. The radiographer who performs the scan will be able to identify the sentinel node as the first lymph node that the radioactive liquid goes into.

Looking for cancer cover that supports you every step of the way?

If you develop new conditions in the future, you can rest assured that our health insurance comes with full cancer cover as standard.

To get a quote or to make an enquiry, call us on 0800 600 500∧

The lymph node removal procedure

Exactly what happens during your surgery will depend on a number of things, including how many lymph nodes are being removed and where they are. If you’re having a sentinel lymph node removed, your surgeon may inject a blue dye into the area of your cancer. This travels to the sentinel lymph node and dyes it blue, which will make it easier for your surgeon to find it.

Lymph node removal can be done as open or keyhole surgery. Which you have will depend on the area of your body being operated on.

In open surgery, your surgeon will make a cut in the affected area and identify the lymph nodes they’re going to remove. They’ll then carefully remove them and possibly some other tissue nearby that may have cancer cells. Your surgeon may put a fine tube (called a drain) in place, to drain fluid from your wound. This will be taken out after a few days or so – ask your surgeon how long you need them for. At the end of the operation, your surgeon will close the wound with dissolvable stitches, non-dissolvable stitches, staples, or skin glue.

In keyhole surgery, your surgeon will make a small cut (or cuts) in the affected area. They’ll use surgical instruments (including a camera), which they’ll pass through the cuts to view your lymph nodes and remove them.

Aftercare following lymph node removal

How long you need to stay in hospital depends on the type of surgery you’ve had. For some procedures, you might be able to go home on the same day, while for others you may need to stay for one or more nights. Your healthcare team will let you know how long you should expect to stay in hospital for.

If your surgeon used blue dye in your operation, it will temporarily stain your pee (urine) a blue or green colour. This is normal and your pee will go back to its normal colour quickly.

Recovering from the anaesthetic

If you’ve had a general anaesthetic, you’ll need to rest afterwards. You might have some discomfort as the anaesthetic wears off, but you’ll be offered pain relief if you need it.

You might find that you’re not so co-ordinated or that it’s difficult to think clearly after a general anaesthetic. This should pass within 24 hours. In the meantime, don’t drive, drink alcohol, operate machinery, or sign anything important. If you’re going home the same day as your general anaesthetic, you’ll need to arrange for someone to drive you. This is a good idea even if you had a local anaesthetic. You should also have an adult stay with you for the first 24 hours.

Taking care of your wound

You’ll be given advice about caring for a surgical wound before you go home, as well as a date for a follow-up appointment. If you have a drain from your wound, you’ll usually have it removed after a few days or so – ask your surgeon exactly how long. Ask who will remove it too – it may be your surgeon or your GP depending on your local arrangements. You’ll have a dressing over your wound. Your nurse or surgeon will tell you when you can remove this.

If your surgeon used dissolvable stitches to close your cut, these won’t need to be removed. They’ll usually dissolve completely within a few weeks, depending on which type your surgeon used. If you had non-dissolvable stitches or staples, you’ll need to have these removed after a week or so. If you have skin glue, this should flake off on its own after a week or two.

Getting your results

After surgery, your lymph nodes will be sent to a laboratory to test for cancer cells. Results are usually sent to the doctor who requested your procedure. Your doctor will talk to you about your results at your follow-up appointment – this might be a week or two after your surgery.

Recovery following lymph node removal

You’re likely to have some pain and discomfort for a while after your operation. Your wound may be sore and swollen. If you need pain relief, you can take over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist for advice.

The recovery time for lymph node removal will depend on your circumstances and type of surgery you’ve had, it could be anything from weeks to months. Your surgeon or nurse will explain how long it should take you to recover. Ask them when you’re likely to be able to get back to your usual activities, including going back to work. Check if there are any restrictions on what you can do while you’re recovering, like strenuous exercise or heavy lifting.

Side-effects of lymph node removal

Side-effects of lymph node removal will depend on where your lymph nodes were removed from. For instance, side-effects of lymph node removal in your armpit may include stiffness in your shoulder. You can do exercises to help with this.

After the removal of lymph nodes in your neck, you may have some weakness on one side of your mouth. This will usually return to normal in a few months.

Complications of lymph node removal

Complications are when problems occur during or after the operation. Complications of having your lymph nodes removed can include the following.

- An infection in your wound. You may need antibiotics to treat this.

- A build-up of fluid in the area around the lymph node area (seroma). This usually goes within a few weeks but your surgeon may need to drain it.

- Injury to nerves near the site of your operation. This may make your skin feel numb or cause tingling or a shooting pain. This should get better without any treatment but it may take weeks or months.

- Persistent pain. This may be due to damage to the tissues, a nerve, or scar tissue forming. Pain can sometimes continue to be a problem for months or even years after your surgery. Your doctor or nurse can give you advice on exercises to help manage pain, or prescribe painkillers if necessary.

- Lymphoedema. This is a build-up of lymph fluid in an area of your body – often an arm or leg. It can be a long-term side-effect of lymph node removal. Seek medical attention quickly if this happens to you. Lymphoedema happens because lymph fluid can’t drain away as well once your lymph nodes are removed. You’re more likely to develop it if you have several lymph nodes removed and if you have radiotherapy. You’ll continue to be at risk of developing lymphoedema for the rest of your life after having lymph nodes removed. But there are many things you can do to keep this risk as low as possible. These include keeping to a healthy weight and being active.

Sepsis (adults)

Sepsis is a life-threatening complication that can develop if you get an infection. Sepsis is a medical emergency. Call 999 or go to A&E immediately if you have any of the following symptoms.

- Slurred speech, confusion, difficulty making sense.

- Extreme shivering or muscle pain.

- Passing no pee (urine) during a day.

- Severe difficulty breathing, feeling breathless, or breathing very fast.

- It feels like you’re going to die.

- Skin changes, such as your skin looking blue, pale or blotchy, or a rash that doesn’t fade when you roll a glass over it.

You’re likely to feel sore and have some discomfort after your lymph node removal. Other side-effects of lymph node removal will depend on where your lymph nodes were removed from. If you had lymph nodes removed in your armpit, for example, you may get a stiff shoulder. Your doctor or nurse will give you advice on how to manage these problems.

See our side-effects of lymph node removal section for more information.

Yes, you can live a normal life without lymph nodes. While they’re an important part of your immune system, your body has a network of several hundred lymph nodes so if you remove a small number, it won’t affect your immunity. But if you have complications of lymph node removal, these might affect your life. For example, one potential complication is lymphoedema. This is a build-up of lymph fluid in an area of your body – often an arm or leg – and is a long-term problem.

See our complications of lymph node removal section for more information.

How serious lymph node removal is depends on which lymph nodes are removed and your personal circumstances. It can be quite a big operation. The recovery time for lymph node removal can be anything from weeks to months.

See our recovery following lymph node removal section for more information.

If you have a lymph node biopsy and cancer is found, you may need to have an operation to remove this and potentially, other lymph nodes. Finding cancer in the lymph nodes means that your cancer has started to spread. Your doctor will talk to you about further tests and treatment.

Cancer in the lymph nodes can be stage 1 or 2 if it hasn’t spread beyond the nearby lymph nodes. But staging cancer is very complicated and there are other things that doctors consider before they confirm your stage of cancer. Ask your doctor or cancer nurse specialist about what stage of cancer you have.

Lymphoedema

Lymphoedema is the build-up of a fluid called lymph, which causes a body part to swell up.

Breast cancer

Other helpful websites

Did our Lymph node removal (lymphadenectomy) information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Mulita F, Lotfollahzadeh S, Mukkamalla SKR. Lymph node dissection. StatPearls Publishing.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 10 July 2023 - Surgery to remove lymph nodes from your armpit. Cancer Research UK. cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 28 November 2023

- Lymphadenopathy. MSD Manual Professional Version. msdmanuals.com, last full review/revision April 2024

- Toomey AE, Lewis CR. Axillary lymphadenectomy. StatPearls Publishing. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 24 July 2023

- Assessment of lymphadenopathy. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 1 September 2024

- Generalised lymphadenopathy. Patient. patient.info, last edited 20 November 2023

- Sentinel lymph node. National Cancer Institute. cancer.gov, accessed 1 October 2024

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with melanoma. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 14 October 2021

- Preparing for surgery. Macmillan. macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 1 September 2024

- Preparing your body. Royal College of Anaesthetists. rcoa.ac.uk, accessed 1 October 2024

- You and your anaesthetic. Royal College of Anaesthetists. rcoa.ac.uk, reviewed April 2023

- Surgery for head and neck cancer. Macmillan. macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 1 March 2022

- Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND). Macmillan. macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 1 May 2022

- Sevensma KE, Lewis CR. Axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy. StatPearls Publishing. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 3 July 2023

- Surgery to remove the lymph nodes for melanoma. Macmillan. macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 1 October 2022

- Wound closure technique. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 22 June 2021

- Caring for someone recovering from a general anaesthetic or sedation. Royal College of Anaesthetists. rcoa.ac.uk, reviewed November 2021

- Wound management and suturing. Patient. patient.info, Last edited 22 October 2021

- Materials for wound closure. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com, updated 21 September 2021

- Biopsy. Lymphoma Action. lymphoma-action.org.uk, Last reviewed July 2022

- Ongoing pain after breast surgery, lymph node removal or radiotherapy. Breast Cancer Now. breastcancernow.org, accessed 2 October 2024

- Lymphoedema. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 1 September 2024

- Reducing your risk of lymphoedema. Macmillan. macmillan.org.uk, reviewed 1 March 2023

- Lymph node removal & lymphedema. National Breast Cancer Foundation. nationalbreastcancer.org, last updated 1 August 2024

- Sepsis. Patient. patient.info, last edited 21 February 2024

- Suspected sepsis: Recognition, diagnosis and early management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). nice.org.uk, last updated 19 March 2024

- What is sepsis? The UK Sepsis Trust. sepsistrust.org, accessed 2 October 2024

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma skin cancer. Cancer Research UK. cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 2 April 2024

- Stage 1 breast cancer. Cancer Research UK. cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 31 May 2023

- Stage 2 breast cancer. Cancer Research UK. cancerresearchuk.org, last reviewed 31 May 2023

- Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor