Ulcerative colitis

- Dr Derek Chan, Consultant Physician and Gastroenterologist

- Rachael Mayfield-Blake, Freelance Health Editor

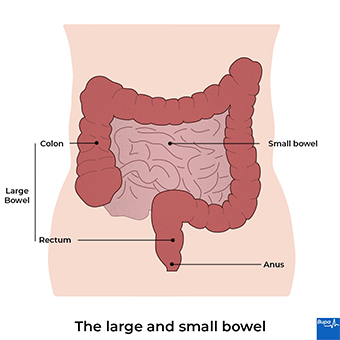

Ulcerative colitis is a long-term condition that causes your large bowel (your colon and your rectum or back passage) to become inflamed (red and swollen). This causes symptoms like diarrhoea (with blood in it), which may come and go, and tummy (abdominal) pain. There are lots of treatments to help control the symptoms of ulcerative colitis.

About ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is one of the main types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The other is Crohn’s disease. In ulcerative colitis, the lining of your large bowel becomes inflamed, and can develop ulcers. If it affects only your rectum (the very end of your large bowel), it is called ulcerative proctitis. But it may spread upwards from here. The affected areas may bleed and produce mucus, which you then pass out when you poo.

Most people develop ulcerative colitis either between the ages of 15 and 30 or when they’re older at around 50 to 70. But you can get ulcerative colitis at any time in your life. Once you get it, you’ll usually have ulcerative colitis for the rest of your life.

Causes of ulcerative colitis

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis isn’t known. It’s thought that it’s probably an autoimmune condition in response to bacteria in your bowel. This means your body’s immune system attacks itself.

Ulcerative colitis runs in families. If you have a close family member with ulcerative colitis, you’re about four times more likely to develop it. Your chance of getting ulcerative colitis may also be affected by your environment and where you live. It’s more common in northern Europe, and in specific groups – for example, people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis symptoms usually come and go. This is called a relapsing and remitting pattern. Your symptoms can disappear (and you’re in remission), sometimes for years, before they come back again (flare-up, or relapse). Flare-ups can last anything from a few days to several months. You may feel well between flare-ups, with no symptoms.

During a flare-up, symptoms of ulcerative colitis may include:

- diarrhoea, often with blood or mucus in it – you may need to rush to the toilet, even at night

- lower tummy (abdominal) pain or cramps, which may go away after you’ve had a poo

- feeling like you still need to go for a poo even when there’s nothing left to pass – this is called tenesmus

- feeling extremely tired – either from the illness itself or lack of sleep, or from losing blood, which can cause anaemia

- losing your appetite

- losing weight

- feeling generally unwell

- a raised temperature

There’s a chance you could develop problems in other parts of your body too. For example, you might get:

- mouth ulcers

- skin rashes

- red or painful eyes

- painful, swollen joints

These problems usually occur during a flare-up, but can also happen while you’re in remission. You may feel anxious, and your symptoms can have a significant impact on your quality of life. For more information, see our section on living with ulcerative colitis.

If you have any of these symptoms, contact your GP for advice.

Diagnosis of ulcerative colitis

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. They’ll also ask about your medical history and if any other members of your family have bowel problems. They may ask you for a sample of poo (a stool sample) to check for bacterial infections in case your symptoms are due to an infection. This sample can also be used to look for a marker called faecal calprotectin. This marker can be raised if you have inflammatory bowel disease flare. They’ll ask you to have a blood test too.

Depending on the results, your GP may refer you to a gastroenterologist (a doctor who specialises in conditions that affect the digestive system).

You might need to have more tests, which can include the following.

- Colonoscopy. Your doctor will do this test to look at the lining of your large bowel to check for any ulcers or inflammation. They may take some samples of tissue (biopsies) from your bowel too. Your doctor may offer you pain relief to keep you as comfortable as possible.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This test is similar to a colonoscopy, but it only looks at your rectum and the lower part of your large bowel. Your doctor can take biopsies during this test too.

- Gastroscopy. This involves putting a narrow tube (gastroscope) into your mouth and down your food pipe (oesophagus). It allows your doctor to look at the upper part of your digestive system. It can help your doctor to work out whether your symptoms may be due to Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

- CT or MRI scans. These will give detailed images of the inside of your body. They can help to show how much of your large bowel is affected by ulcerative colitis.

- X-ray. This may help to rule out serious problems like toxic megacolon (see our section on complications of ulcerative colitis).

Treatment of ulcerative colitis

Treatment for ulcerative colitis can control your symptoms and prevent flare-ups. The treatment you have will depend on how severe your ulcerative colitis is, and how much of your large bowel it affects. A team of healthcare professionals with specialist knowledge of inflammatory bowel diseases (your IBD team) will care for you.

Medicines

You may need to take different medicines when you’re in remission and when you’re having a flare-up. It’s important to keep taking your medicines, even if you feel well.

If you have a severe flare-up of ulcerative colitis, you may need to go into hospital urgently. You’ll need specialist care and intravenous medicines (these medicines are given directly into your vein).

Medicines for ulcerative colitis include the following.

Aminosalicylates

Aminosalicylates are also known as 5-ASAs and include mesalazine. You can take these as tablets or as a preparation that you put into your bottom (back passage). This can be a suppository (a dissolvable capsule you put up your bottom) or enema (a foam or liquid that you put up your bottom). You can take aminosalicylates during flare-ups and when you’re in remission, to help prevent symptoms.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids include hydrocortisone, prednisolone and budesonide. You may need to take these if aminosalicylates don’t control your symptoms when you have a flare-up or you can’t take aminosalicylates for some reason. You can take steroids as tablets or as a suppository or enema into your bottom. If you have a severe flare-up, you may have steroids intravenously (through a drip in a vein) in hospital.

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants such as azathioprine and mercaptopurine work by calming down your immune system. Your doctor may prescribe these if you keep needing to take steroids for flare-ups or after a severe flare-up. You take these immunosuppressants as tablets.

Biological drugs

Biological drugs for ulcerative colitis include infliximab, adalimumab, ustekimumab, and vedolizumab. But your doctor may suggest these if you’re having flare-ups and other treatments aren’t working or you can’t take them for some reason. Biological drugs are usually given as injections – either into a vein or under your skin. Some, you take as tablets. If you get on well with them, you might continue taking them when you feel better, to prevent further flare-ups.

JAK inhibitors

Tofacitinib, filgotinib, and upadacitinib are JAK inhibitors. These block enzymes that your immune system uses to trigger inflammation. You can take them as tablets. You might need to take these if you have moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and other medicines haven’t worked or aren’t suitable for you.

Ozanimod

Ozanimod affects the way your immune system works. You take it as a tablet. You might need to take ozanimod if you have moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and other medicines haven’t worked or aren’t suitable for you.

If you have any questions about your medicines, ask a pharmacist or doctor. Let your doctor know if you’re trying to get pregnant because you shouldn’t take some of these medicines for ulcerative colitis if you’re pregnant.

Surgery

Surgery for ulcerative colitis is done as keyhole surgery wherever possible. It involves removing all or part of your large bowel. You may need surgery for reasons that include the following.

- You’re getting lots of flare-ups and medicines aren’t helping.

- You keep needing steroids to control your symptoms.

- Your doctor has identified changes in your bowel during check-ups for bowel cancer (see our section on complications of ulcerative colitis).

- You’re having a severe flare-up and you need surgery as an emergency treatment.

- You’d prefer to have surgery rather than keep taking medicines.

Around 10 in 100 people with ulcerative colitis have surgery within 10 years of being diagnosed. But this number is getting lower all the time as better treatments become available.

Surgery for ulcerative colitis often involves having an ileostomy. This means your surgeon will bring the end of your small bowel to open on the surface of your tummy (this is called a stoma). It’s a way for your body to get rid of waste products. You wear an ileostomy bag over the stoma, to collect the waste. You may need to have a temporary or a permanent ileostomy.

Your doctor will talk to you about what kind of operation is best for you and what’s involved. If you’re considering having surgery, it’s important that you discuss all the pros and cons with your doctor first. The most common types of surgery for ulcerative colitis are discussed here.

Pouch surgery

This is also called ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) surgery. Your surgeon will remove your entire large bowel – both your colon and rectum. They’ll then make a pouch from the end of your small bowel, and stitch this to your anus. The pouch can store waste products and your poo can pass through your anus as normal. This operation is often done in two or three stages. You may need a temporary ileostomy while the new pouch heals.

Subtotal colectomy with ileostomy.

In this procedure, your surgeon will remove most of your large bowel but leave your rectum. You’ll need to have an ileostomy but this may not be permanent. Later on, you may be able to have pouch surgery.

Proctocolectomy with permanent ileostomy.

If you have a proctocolectomy, your surgeon will remove all of your large bowel, including your colon and rectum, and your anus. You’ll need a permanent ileostomy if you have this surgery.

GP Subscriptions – Access a GP whenever you need one for less than £20 per month

You can’t predict when you might want to see a GP, but you can be ready for when you do. Our GP subscriptions are available to anyone over 18 and give you peace of mind, with 15-minute appointments when it suits you at no extra cost.

Complications of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis can lead to a number of complications.

Toxic megacolon

Toxic megacolon is when your large bowel becomes enlarged and swollen as part of a severe flare-up. You’ll probably feel very unwell with a high temperature and tummy pain. It’s uncommon, but if you get these symptoms, seek urgent medical attention because you might need treatment in hospital.

Bowel cancer

Ulcerative colitis can increase your risk of getting bowel cancer. The risk is higher if you’ve had ulcerative colitis for a long time, if it’s not well-controlled, and if a lot of your bowel is affected. Your doctor may recommend you have regular colonoscopies to check for any signs of cancer. This will usually be from around 10 years after you first get symptoms. Keeping your colitis under control may help to reduce your risk of bowel cancer.

Perforation

Perforation (a tearing) of your bowel can be a complication of a severe flare-up. You might have severe pain, as well as a fever, nausea and vomiting. Seek urgent medical help if you develop these symptoms.

Anaemia

You may develop iron-deficiency anaemia if you have ulcerative colitis. The anaemia is caused by a lack of iron in your diet, poor absorption of iron from food or blood loss from your gut.

Vitamin deficiencies

If you have a poor appetite, don’t eat enough or have ongoing diarrhoea, you may develop a vitamin deficiency. You may need to take vitamin supplements.

Osteoporosis

If you have ulcerative colitis, you’re more at risk of developing thinner and weaker bones due to osteoporosis. This can happen because of ongoing inflammation, smoking, taking steroids or not exercising much. You may also not get enough calcium from your diet.

Ulcerative colitis is also linked to a health condition called primary sclerosing cholangitis. It affects your bile ducts (tubes that connect your liver and gallbladder to your small bowel). Primary sclerosing cholangitis causes your bile ducts to become more and more inflamed and damaged over time. You may need to take treatments to control your symptoms if you develop primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Living with ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a life-long condition that can affect you physically and emotionally. Flare-ups can have a big impact on your social life, education, or work. But that doesn’t mean you can’t live life to the full.

Take care of yourself

It’s natural that living with ulcerative colitis can make you feel stressed at times. Stress can sometimes trigger flare-ups, so you may find it helpful to try some relaxation techniques. These include deep breathing, meditation, yoga and mindfulness.

If you take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, they may trigger ulcerative colitis. Instead, take alternative over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol.

Regular exercise can help to give you a boost and make you feel better. It can also improve your general health and help to keep your bones and muscles strong. This is important because if you have ulcerative colitis, you may be more at risk of osteoporosis .

You don’t have to eat a specific diet if you have ulcerative colitis but some foods may make your symptoms worse – for example, milk. Aim to eat a healthy balanced diet and keep a food diary to help you identify any problem foods. If you’re unintentionally losing weight or your doctor thinks you aren’t getting the nutrients you need, they may refer you to see a dietitian. You may need to take supplements of, for example, calcium and vitamin D to get everything you need.

Being prepared

Flare-ups can be unpredictable. To help prepare, make a flare-up plan with your doctor or nurse. This may involve adjusting the medicines you take, for instance.

If you feel anxious about going out, it can help to plan ahead. Find out where the nearest public toilets are. You may find it useful to carry a card to help tell people if you need to use the toilet urgently. If you’re worried about not getting to the toilet quickly enough, carry spare clothing in your bag so you can change. You may also want to carry moist wipes, and plastic bags for soiled clothes.

If you’re going on holiday, make sure you have enough medicine to take with you, including any you need for a flare-up. In case of delays, take extra medicines with you if possible and a doctor’s note to say what they’re for, especially if you’re flying.

Getting support

If you tell your family and friends about your condition and how it affects you, it may help them to give you the support you need. Your IBD team will also support you and there may be a helpline or email you can contact. Keep these to hand, and always seek advice as soon as you need it. Support groups, as well as online chat forums and message boards can offer a chance to talk to other people having similar experiences. See our section on other helpful websites.

If you take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, they may trigger ulcerative colitis. Instead, take alternative over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol. Other things that can trigger ulcerative colitis include an infection in your gut.

For more information, see our sections on causes of ulcerative colitis and living with ulcerative colitis.

The only cure for ulcerative colitis is surgery to remove all of your large bowel. But there are many treatments available that can help to keep your symptoms under control and these may be enough for you.

For more information, see our section on treatment of ulcerative colitis.

Your risk of developing ulcerative colitis is higher if a close family member has it. But having a family member with ulcerative colitis doesn’t mean you’ll definitely get it. Ulcerative colitis is likely to be caused by a combination of things, and genetics is just one potential cause.

For more information, see our section on causes of ulcerative colitis.

Ulcerative colitis can often come on very slowly and gradually. You might notice bleeding and passing mucus from your bottom first. You may have diarrhoea and pains in your tummy too.

For more information, see our section on symptoms of ulcerative colitis.

Other helpful websites

Discover other helpful health information websites.

Did our Ulcerative colitis information help you?

We’d love to hear what you think.∧ Our short survey takes just a few minutes to complete and helps us to keep improving our health information.

∧ The health information on this page is intended for informational purposes only. We do not endorse any commercial products, or include Bupa's fees for treatments and/or services. For more information about prices visit: www.bupa.co.uk/health/payg

This information was published by Bupa's Health Content Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been reviewed by appropriate medical or clinical professionals and deemed accurate on the date of review. Photos are only for illustrative purposes and do not reflect every presentation of a condition.

Any information about a treatment or procedure is generic, and does not necessarily describe that treatment or procedure as delivered by Bupa or its associated providers.

The information contained on this page and in any third party websites referred to on this page is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice nor is it intended to be for medical diagnosis or treatment. Third party websites are not owned or controlled by Bupa and any individual may be able to access and post messages on them. Bupa is not responsible for the content or availability of these third party websites. We do not accept advertising on this page.

- Lynch WD, Hsu R. Ulcerative colitis. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books, last updated 5 June 2023

- Ulcerative colitis. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. cks.nice.org.uk, last revised April 2020

- Ulcerative colitis. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 1 November 2023

- Ulcerative colitis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 3 October 2023

- Ulcerative colitis. Your guide. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed May 2021

- Flare-ups. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed August 2023

- Tests and investigations. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed September 2022

- Biologics and other targeted medicines. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed July 2023

- Infliximab. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 1 November 2023

- Infliximab. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed November 2020

- Tofacitinib. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 1 November 2023

- Filgotinib for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 1 June 2022

- Ozanimod for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, published 5 October 2022

- Ozanimod. NICE British National Formulary. bnf.nice.org.uk, last updated 1 November 2023

- Surgery for ulcerative colitis. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed October 2022

- Ulcerative colitis. MSD Manuals. msdmanuals.com, reviewed/revised January 2022

- Colorectal cancer prevention: Colonoscopic surveillance in adults with ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease or adenomas. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk, last updated 20 September 2022

- Bowel cancer risk. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed April 2019

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis. BMJ Best Practice. bestpractice.bmj.com, last reviewed 6 October 2023

- Mental health and wellbeing. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed June 2020

- Food. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed February 2023

- Travelling with Crohn's or colitis. Crohn's and Colitis UK. crohnsandcolitis.org.uk, last reviewed June 2022